BELLOWS FALLS — Carolyn Frisa serves as the vice-chair of the Board of Trustees of the Rockingham Free Public Library. She has served on the board three years, including the contentious months leading up to the firing of Library Director Célina Houlné in 2013.

But a new twist has taken place in the life of the busy civic volunteer and entrepreneur.

“I stopped using email,” Frisa said.

Frisa said that in the wake of months of blanket public- document requests to the board, following the controversial firing of Houlné, “I was advised by Amy Howlett [regional consultant for Vermont Department of Libraries] to stop” using electronic communications as a means of conducting board business.

When the board changed its makeup after elections in March, Houlné was rehired as a condition of settling a wrongful dismissal lawsuit.

It was under Jan Mitchell-Love and Deborah Wright's leadership as chair and vice-chair, respectively, that Houlné was fired in August 2013.

Frisa, who had voted against the firing and voted in favor of rehiring Houlné, became vice-chair after Deborah Wright, who then held that post, lost her bid for reelection.

Also in March, incoming trustee David Gould took over the chairmanship from Mitchell-Love, who remains on the board.

Since that time, board members have frequently been subject to public records requests that continue to the present. Members of the public and trustees have been overheard referring to the barrage of public-records requests as a “witch hunt.”

'Blanket' requests

Frisa recalls that, following her vote against firing Houlné, she received her first public document request. It was her first ever, and she recalls that she did not even know that public boards are required by law to keep a record of all their communications as board members. She sought advice and was told that she had to comply.

Frisa, who said she loves efficiency, immediately set herself up with systems to do so on her computer.

But Frisa said she was juggling care for her newborn with work at the time.

She said that starting with that first request, she has lost between $6,000 and $10,000 worth of her professional time, which she spent by complying with that and other subsequent “blanket” public-documents requests for “every single email” made to her individually and to the board as a whole.

Frisa, whose Works on Paper at the Square offers professional art and historic document conservation consultation for clients ranging from museums to libraries, has been dealing with these requests at a critical time for her enterprises: According to federal statistics, approximately half of all business startups fail within the first four years, as illustrated by the local retail turnover.

At the heart of Vermont's “sunshine laws” - the Open Meeting Law and the Public Records Law - is an intent to assure transparency, prevent backroom deals, and expose hidden agendas to an informed public, so they may hold their government accountable.

But the kinks are still getting worked out as a volunteer board of library trustees struggles to comply with these laws that, by design, ignore the intent of citizens who invoke them.

Complying with two kinds of requests

Donald Maurice Kreis has seen both sides of this issue. He has been served with public document requests, and he has requested public documents.

A senior energy law fellow at Vermont Law School, an attorney in private practice, and a former general counsel of the New Hampshire Public Utilities Commission, Kreis is also a former reporter with the Associated Press and the Maine Times.

He said he has found, in general, people who request access to public documents fall into two categories: those who have a beef against the government, and journalists.

When the public records law is invoked, the tone of the interaction can become adversarial and formal. In his experience, journalists' requests are often conducted more informally, Kreis noted, though not always. To save time and costs, journalists often collaborate with the custodian of the records to narrow down their requests.

When a public records request can be narrowed to an event, a time or date, or a particular subject, the collaborative nature of such a request saves time for both parties.

But in an illustration of what Kreis describes as “adversarial” requests, complying with Vermont's access to public records law has played a significant role in the controversy leading up to, and following, Houlné's dismissal and subsequent rehiring.

Anecdotal accounts of public records requests of the board (as individual trustees and the full board) and reinstated library director, just since March elections, are estimated to be about one a week.

And a majority of those have been blanket requests from Wright for “all emails” within a range of dates.

Board members complain of the time spent complying with frequent “blanket” requests for emails in the aftermath of Houlné's rehiring in June.

Gould characterized the requests as “harassment” by Wright.

“She has learned how to use the state laws to harass elected public officials. The amount of time that I have spent answering, responding, and looking up, trying to satisfy what she was after (and it's never really been clear why she wanted all of those emails), when she simply could have called and said, 'What's going on?' I would have been happy to talk to her.”

“But,” Kreis reminds, “the law is clear - what motivates these requests is irrelevant.”

Gould, however, was adamant that he believes in so-called “sunshine laws.”

“The basic tenets are sound. They were set up to help stop the backroom political dealings that we have all heard about or known about. The general public has to have an avenue for getting to this kind of information. I truly believe that.”

But, he said, “By the number of these requests, it becomes an abuse of the law.”

“It saddens me greatly,” Gould said. “[Wright] is smart, intelligent, creative, clever - but for some reason, she has chosen to use those attributes in negative ways. Just think what could be accomplished if we could get her turned around.”

Wright has since filed a complaint with the Vermont Attorney General's office, citing 11 concerns of the trustees violating the letter or the spirit of the state open-meeting and public-records laws. [Story, page A1.]

Rules and consequences

Complicating things further, members of volunteer boards in particular often have no previous background serving on a public board and, until recently, no training in “sunshine laws” was available for them.

The Vermont League of Cities and Towns (VLCT) has recently begun to provide training for both compliance with public records and open meeting laws for boards of public bodies.

A public official cannot refuse to comply without breaking the law and risking a lawsuit brought by the requester.

With recent changes to the statutes, however, the costs and fees of a court case become the responsibility of the complainant if the court finds in favor of the agency.

Kreis points out that if the responder to the requests can present a case that successfully shows intent to harass or intimidate a public board or official, then those costs and fees are also likely to become the responsibility of the complainant.

But not many cases get this far, he said, as a result of these changes.

Saving time

In an effort to help compress the time and volume involved in such requests, the law provides means to cut down on the time and volume spent in complying with requests:

The law states that “a public agency shall consult with the person making the request in order to clarify the request or to obtain additional information that will assist the public agency in responding to the request and, when authorized by this sub-chapter, in facilitating production of the requested record for inspection or copying.”

In some predefined “unusual circumstances,” the law allows the agency to “request that a person seeking a voluminous amount of separate and distinct records narrow the scope of a public records request.”

Wright's formal requests have provided no opportunity for a narrowing down or definition of what she is looking for, and individual trustees say they lack the training to negotiate those “unusual circumstances” to make fulfilling the requests less onerous.

Frisa noted that mandatory training for incoming trustees would provide the knowledge of how to respond in a more time-saving manner.

Reimbursement

Other public officials have also voiced their concerns about the number of, and unlimited scope of the public document requests they receive.

Town manager Willis “Chip” Stearns II told Secretary of State James Condos during a presentation in Bellows Falls in 2013 that he spent about 20 hours of his own time, over and above the 60 to 65 hours he devotes to his job, complying with one request - and the requester never picked up the resulting documents.

Condos was sympathetic but said, in such a case, one recourse would be to establish a cost structure that takes into account material costs and staff time.

According to Leven, “Actual cost charges can include the actual cost of staff time associated with responding to the public records request and that exceeds 30 minutes.”

The town now has such a fee structure in place for public request costs, for staff time, and material costs. The records still need to be gathered, and they could potentially sit uncollected, but such a system can at least mitigate the expense of fulfilling public records requests.

But Frisa said the Secretary of State's office has advised her that she cannot be reimbursed.

Frisa said she was told that the extra time she must put into requests directed to her personally as a trustee has no monetary value because she is a volunteer.

She describes this situation as a huge hole in the law.

Who's in charge?

In 2013, the law was changed to clarify the responsibility of state agencies to provide an administrator of public records.

Now, anyone requesting public documents at the state level is directed to a specific person in charge: the designated administrator for each department.

But this requirement for municipalities to do the same was removed from the law. The municipal mandate to hire an administrator was removed after complaint by the Vermont League of Cities and Towns, a lobbying group that represents the interests of municipal governments in the state lawmaking process, about the cost to municipalities.

Prior to the law change, public document requests would have been unambiguously directed to the municipal manager's office, leaving individual trustees out of the fray.

Deputy Secretary of State Brian Leven responded to clarification of this amendment.

“Unfortunately, the statute does not address whether a volunteer is considered 'staff,'” Leven wrote. “Also, I still think that the legal custodian of the record is the agency and not a specific person. Each state agency is required to appoint a public records officer to take primary responsibility for managing that agency's records.”

The library trustees voted last November to establish a designated email address as a public-records repository on the advice of Town Attorney Stephen Ankuda. They voted not to blind-copy anyone on emails regarding official library business. And they voted to create a policy regarding trustee email communication. All seven trustees unanimously voted for these changes.

But nowhere in any of these votes did the trustees officially establish an administrator. Unofficially, Youth Librarian Sam Maskell and Reference and Historical Collections Librarian Emily Zervas have been responding to public-records requests.

In the absence of a policy that otherwise specifies the administrator, “The custodian is the public agency, in this case, the board of library trustees,” Leven said.

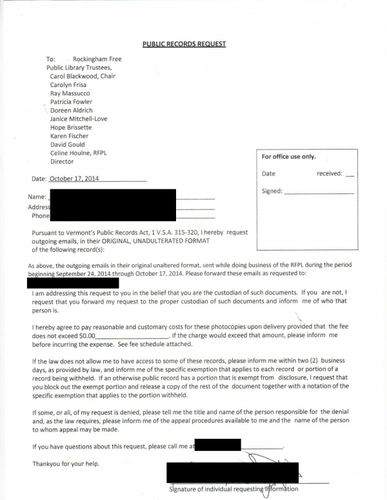

Then-chair David Gould had responded to an Oct. 17 records request from Wright by directing her to the repository she and the previous board had established nearly a year earlier. Other board members, including current chair Carol Blackwood and vice-chair Frisa, had responded in the same way to similar requests.

Wright requested all outgoing emails between Sept. 24 and Oct. 17, stating that she believes Gould to be the custodian of those records.

Leven responded in a further request for clarification: “'Custodian' is not defined in the public records act, but the public agency is the custodian of records it produces or acquires. The agency then must determine what person or persons will be responsible for public records and for responding to public records requests.”

But Wright has asserted that referring to the repository was an inadequate response, and trustee and former chair Jan Mitchell-Love has agreed.

Gould had responded to the request by directing Wright to the repository that she and her colleagues on the previous board had established nearly a year earlier.

In an email supporting Wright's objections, Mitchell-Love told Gould: “The repository is not a person; it is a storage place. As such, it cannot serve as a custodian.”

She described the repository as “a voluntary storage place” that is “subject to human error.”

“When we set it up, Mr. Ankuda said - and we all agreed - that the repository wasn't a satisfactory concept in a lot of ways, but at least there would be a place, we reasoned, where we could go to find emails of trustees no longer on the board, deceased, etc.

“We might not be able to find all of them, but it would be a start. And that's all it was intended to be.”

“You are the custodian of your emails as I am of mine,” Mitchell-Love wrote to Gould. “And as part of your responsibility as custodian you have to keep your correspondence securely and be able to produce it when asked for it in a public records request. You also have three days to reply to Ms. Wright.”

At the Oct. 28 trustees meeting, the issue was discussed in public comment.

Citing requests that have “necessitated over 22 separate responses from individual trustees” and two requests to Houlné, Arnold Clift identified Wright and recommended the library and trustees ignore the requests and let her take them to court.

“As a former trustee, Ms. Wright is well aware of the time-consuming effort needed to respond to such requests, especially since some of them are very broad in scale,” said Clift, whose wife, Elayne, also served as trustee. “One can only surmise the real motive of why some many requests.”

Noting that the court may provide “penalties and sanctions against any litigant whose complaint is deemed by the court to constitute harassment,” Clift suggested that “the board of trustees consider not reply to any further public records requests from Ms. Wright at this time and instead allow Ms. Wright to pursue the matter in court where it may be judicially resolved.”

Clift also suggested that the library director be named as the official custodian of records “for the purposes of the public records requests law.”

He proposed that “[a]ll official library documents produced or acquired by trustees or staff be deposited with the custodian and all public-records requests be handled and responded to by the custodian.”

Joel Love, the husband of trustee Mitchell-Love, called Clift's suggestions “totally off base,” calling his proposal “unenforceable and illegal” and rebuked him for his words about Wright.

“You cannot designate a custodian. You should be really careful about whether you do this, because you cannot force any of the trustees to put their stuff into this repository,” Love continued. “The only way to do it is to have the only means of communication be forced upon them using an email system that automatically deposits this.”

Love asked Frisa to provide the past two years of her emails. “And she needs to reply to me and send me the emails because I asked for them in that electronic format,” he said.

“In addition to that, I think Mr. Clift was doing nothing but making a veiled threat against a private citizen who has every right [to the information],” Love added.

“The requestor's identity and motive are irrelevant in responding to a public records request,” Love said, citing a publication from the Vermont League of Cities and Towns.

Frisa said that the board needs to have a clear policy for handling public records requests, and it was suggested that this be taken up by the policy committee, which met Nov. 13.

On Oct. 29, Leven weighed in from the Secretary of State's office.

“The board should designate a person or persons who will be responsible for discharging the duties of the custodian. This person could be the library director if the board chooses.” Or it could officially be Maskell or Zervas, who have informally been serving in the role.

Recourse for boards

If a public board or individual trustees believe - as Gould does - that public records requests are being filed to harass or intimidate, relief or recourse might be found in the judicial system.

But to get there, a board would have to break the law.

“There comes a point where the RFPL trustees can just deny [the public records requests] and basically say in effect, 'if you really want us to fork over the documents in response to your harassing and hostile requests, you're going to have to get a judge to tell us to do it,'” Kreis said.

Then, he continued, “The person who is making the request and not getting the document would have to file a lawsuit and RFPL trustees would have to appear in superior court to respond.”

Kreis said, if requests can be proven to violate Rule 11 of the Vermont Rules of Civil Procedure (VRCP), the court “is going to be parsimonious about what kind of relief it orders.”

That rule says that presentations to the court can be found to have an “improper purpose, such as to harass, cause unnecessary delay or needless increase in the cost of litigation.”

The rule also provides that what is being brought before the court be “non-frivolous.”

Should the court decide that violations of any of Rule 11b apply, sanctions on the “attorneys, law firms, or parties” that violated those rules may be imposed.

In this case, court costs and attorney fees would be the responsibility of the complainant.

And, Kreis said, this potential responsibility illustrates why these kinds of lawsuits rarely make it to court.

A deal-breaker

Frisa said the past year has educated her as to her responsibilities for maintaining public records, but she has stopped using emails altogether, saying that she can both drop off and pick up all public documents from the library.

Frisa also noted the number of blanket requests she has been receiving.

The requests, she said, appear to have “no real objective” and are time consuming to fill, with the threat of breaking the law if the requests are not fulfilled.

She cited the requests as one reason for the widespread problem of getting people to sit on volunteer public boards.

And when her term is up in 2015?

She will be “moving on,” she said.