It starts on an August day, above Flathead Lake in Montana, just a few moments before I head to a wedding.

My cell phone rings. I think of turning it off. I'm on vacation. It's a special day. My children are here, my closest friends. Who would I need to talk to? I check to see.

A Vermont number. My sister.

And so it starts:

“Liz? It's Maggie.”

“Maggie?” I ask. Her voice is lower than usual. Dark.

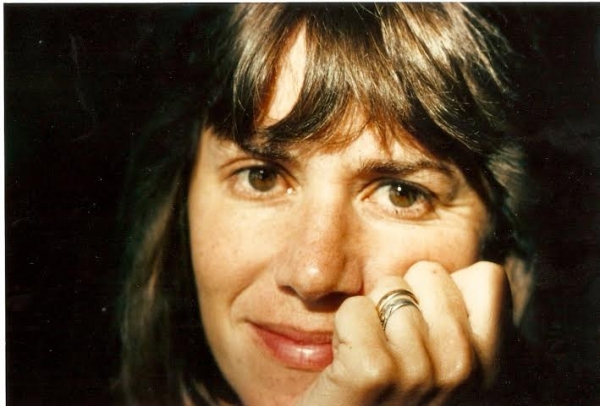

My heart jumps a beat. Maggie's voice is never dark. She is one of those people who seem to have descended from hummingbirds. She is tiny and light, and she never lands long enough for you to really know what's going on in her head. Always moving. Always chipper. Here. There. Gone. Back again.

“What's the matter?” I ask.

“I'm sick.” That's all she says.

A landscape bigger than Montana opens up between us. We both fall in.

“Sick? What kind of sick?”

“Cancer,” she whispers. “I'm very sick.”

Now it's her words that take my breath away. Finally, I ask her what has happened and she tells me a jumbled tale of having weird symptoms, ignoring them, thinking they were one thing, and then finding out they were something quite different. Cancer. Lymphoma. The kind she will die from soon if she doesn't start treatment.

I feel something pulling at me from across the country, but even more so from deep within. As if there is a buried magnet in my body, quivering to the pull of my sister. What is the deepest part of the body? Is it the blood? The bone? The marrow of the bone?

I don't even know what that means: the marrow of the bone. I will find out later.

* * *

After seven years of remission, the cancer comes back. Or rather, it never fully succumbed to the treatment. A few little cells (and maybe even just one) have been hibernating.

Now they are awake and duplicating in Maggie's blood, her lungs, her lymph nodes. She caught it fast, but it's spreading faster, and the only way to beat it this time is with a bone marrow transplant from a genetically matched donor.

Before that can happen, a match must be found. But even before that she has to take a potentially lethal dose of chemotherapy. And this time she also has to take the bullets of full-body radiation - so that her cancer-laden blood cells are eradicated to make way for cells from the donor, should one be found.

I've never liked the way war jargon is applied to cancer treatment, but in this case it seems appropriate. I don't mention this to Maggie, but I've recently learned that chemotherapy was developed after World War I, when changes were observed in the bone marrow cells of soldiers exposed to mustard gas.

At first Maggie refuses treatment, even when her doctors tell her that without it she will live only a few weeks. The thought of what happened the last time hits her like a truck; it barrels down the road and slams into her dignity. All she can think of is vomiting and hallucinating and losing her hair and living like a ghost as the whole world passed her by.

“I will not go through that again,” she tells the doctor as we sit in his examining room on a freezing February day, in the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in New Hampshire, horrified to be in the same room again seven years later, with the same doctor, the same nurse, the same questions, the same lack of conclusive answers.

The doctor convinces her that she can start the chemotherapy and stop at any point. And while she begins treatment, they will search for a bone marrow donor.

They will test each of us sisters - not her children or other relatives - because siblings present the best chance of finding a “perfect match,” one where all the genetic markers line up. The closer the genetic markers, the more successful the transplant. There's only a 25 percent chance of a sibling match, and a smaller chance of the match being perfect.

If none of the sisters are a close enough match, they will search the international donor bank, where there's an even lower likelihood of getting a high-degree match.

If a match is found, and if Maggie tolerates (code for survives) the high-dose chemotherapy and radiation, and if it can rid her body of the lymphoma, she can choose to go ahead with the transplant. But for now, all she has to do is start the chemo, and all the sisters have to do is get our cheeks swabbed and wait for the results.

Maggie nods her head OK. That's her level of buy-in for now. But it's enough to begin.

We go straight from the doctor's office into the maze of the hospital for her first chemo treatment. I sit with her in the infusion suite. That's what the chemotherapy area of the hospital is called - the infusion suite. All around us, fellow refugees from normal life lie huddled in heaps of bedding and tubes. Others rest in lounge chairs, under warmed blankets that the angel nurses replenish frequently. Friends and family make quiet conversation, or stare out the windows as the New Hampshire sleet pelts the glass.

I watch Maggie watching. A young man in the bed next to hers is receiving his first chemotherapy infusion; he practically vibrates with anxiety. An older woman - a chemo veteran - sits alone in a reclining chair, reading. She's bald and sunken-eyed, with an expression of wry acceptance. I smile at her, and she winks.

Before I leave, I gather up my courage and tell Maggie I'm thinking of going on a vacation to the Caribbean. Saying the words “vacation” and “Caribbean” in the chemo suite seems cruel; I feel like one of the evil stepsisters going to the ball, leaving Cinderella behind to pick lentils out of the fireplace.

“I won't go if you don't want me to, Maggie,” I say.

“No! Go,” she pleads. “I want you to live your own life. At least one of us should. Promise?”

“OK. I'll go. I'll enjoy it for the two of us.”

“Well, don't enjoy it too much,” Maggie says.

And so here we are, in the Miami airport, changing planes, heading to a Caribbean island. As I sit next to my husband in a row of orange bucket seats, I already feel my body uncoiling. The warm sunlight streams through the tall airport windows. Maybe I will be able to do what Maggie begged of me - to forget about her for a few days. I lean back and exhale.

My cell phone rings. I take it out of my purse, see the name of the hospital, and brace for awful news. I show the caller ID to my husband. He sits down.

It's the bone marrow transplant coordinator calling to tell me that the lab results for all the sisters have come back.

“I have good news!” the nurse says. She seems overjoyed to be the bearer of positivity. I can only imagine how rare this is for her.

“We found a match for Maggie,” she exclaims. “Are you sitting down? It's you!”

I'm too stunned to reply.

“And there's even better news,” the nurse continues. “You're a perfect match! All 10 genetic markers lined up with Maggie's.”

She begins explaining the science of genetic tissue testing, but I tune her out. My mind goes in several directions at once: Did I imagine I would be perfectly matched with Maggie? No, not really. If I had to guess, I would have picked one of the other sisters. I wonder if they'll be jealous, or maybe they'll be relieved, or probably both.

I wonder if it's dumb luck that Maggie and I are perfectly matched - or is it fate, kismet, karma? It feels preposterous - like a science fiction story.

Or maybe it's a miracle. I'm not sure who gets to determine such things, but this feels like a miracle to me.

* * *

A few weeks later, I buy a big hardcover book about cell biology and try to carve some new neural pathways in my brain in order to understand the most basic information. I am motivated to fall in love with bone marrow and stem cells, so I stay up late every night, reading Essential Cell Biology.

I discover that although bones seem as dead as rock, they are actually super alive. They are like living layers of geological sediment protecting a molten core. The core of the bones is the marrow, and in the marrow are the stem cells, the source of life. Stem cells are also called mother cells because they have the potential to create many types of new cells that your body needs in order to live.

The human body is composed of one hundred trillion cells - give or take a billion - with each cell assigned a specialized function, like skin cells, blood cells, muscle cells, organ cells, brain cells. Specialized cells do not live very long, so the body needs to replace them continuously.

I used to think of my body as a constant - a trusty chariot that would cart me around till death do us part. But in actuality, my body today is not what it was yesterday or what it will be tomorrow.

Humans shed and regrow skin cells every 27 days, making almost 1,000 new skins in a lifetime. Each day, 50 billion cells throughout the body are replaced, resulting, basically, in a new chariot each year. Every second, 500,000 cells die and are replenished. Red blood cells live for 120 days; platelets live for only a week; white blood cells live for a mere eight hours.

And then there are the stem cells that live deep within the bone marrow. Unlike specialized cells that die and must be replaced, stem cells are self-renewing - they divide in unlimited numbers and become new cells.

Some of those new cells remain stem cells, and some leave the bone marrow and flow into the bloodstream, magically morphing themselves into whatever kind of specialized cells the body needs. A stem cell is like a mother. She sends her children out into the world to become who they were born to be.

When doctors harvest bone marrow from a donor, it's the stem cells - the mother cells - they are after. The premise is pretty simple: Destroy the bone marrow in the cancer patient and replace it with several million healthy stem cells from a donor. Then do everything possible to help those donor stem cells engraft in the cleaned-out cavities of the patient's bones.

If all proceeds according to the plan, the mother cells make themselves at home in the new bones and begin to self-renew, building a new bone marrow factory where baby blood cells are produced and sent into the bloodstream, bringing the patient back to life.

Sounds like a good plan, but it's also a dangerous one, because in preparing the patient for the transplant with high- dose chemotherapy and radiation, healthy cells are collateral damage. The patient must endure a near-death experience in order to live.

Sitting in the dark quiet of my house, underlining sentences in Essential Cell Biology, I can almost feel the river of life and death, change and rebirth, flowing in my bloodstream. I shut the book and close my eyes and say a quick hello and thank-you to my stem cells just in case we'll be calling on millions of them soon.

* * *

Once again, we traipse into the cancer ward at the hospital to meet with the oncology team. Their team: one doctor; one nurse; one transplant coordinator. Our team: Maggie's partner and kids; me; and, of course, Maggie, her clothes hanging off her tiny body, her eyes looking even larger and darker than usual.

We crowd into the small, antiseptic examining room. We are talking and joking, happy to be with one another despite the jittery circumstances. Our noise and textures and odors bring the forbidden mess and germs of the world into the hospital. We seem completely out of place, until I remind myself that this is what the place is made for - the mess and germs of being human.

It's time for Maggie to decide. We take our seats. There are so many of us, I double up with my nephew and we hold onto each other.

The doctor reviews the options: if Maggie chooses not to proceed with the transplant, she will die soon, and if she chooses the transplant, it may kill her. Of course, he doesn't come right out and say this - he never does - but that's the hidden message in his vaguely worded script.

And if she survives the transplant, we ask again, are there any numbers of months or years to hang this decision on? Again, vague answers that we have already heard.

Although people surround her in the crowded room, I know Maggie feels alone, wrestling with conflicting magnetic pulls. The pull to live for as long as possible, here on Earth, with us. To experience the softness of another spring, the humid heat of summer, the winter's shocking cold, the joy of love, the sadness of loss, the beauty, the pain, the mess.

And then, the other pull - the pull to die, to surrender, to say no to more chemotherapy and radiation and transplant and months of drug-induced nausea and isolation and the unrelenting anxiety that the cancer may return. To say good-bye now, to leave with some dignity while she still can. I don't know which path I would choose or she should choose. I reach over, stroke her arm, and silently pray.

I say “silently” because prayer is not something Maggie relates to; that's putting it mildly. Last week, a friend e-mailed and pronounced she was praying for Maggie's health. This infuriated Maggie, as if without asking our friend had conscripted her into the faith.

Maggie called me immediately to rail against the stupidity of religion. I proposed that our friend's beliefs might not be what she imagines them to be - that intelligence and spirituality are not diametrically opposed. That you can be a legitimate, thinking person and still listen to Christian music on the radio.

“This is why I'm surprised you and I are a perfect genetic match,” Maggie replied. “What if I become more spiritual if we do the transplant? If my blood is your blood?”

“Yup. Before you know it, you'll be speaking in tongues,” I said.

“No, really, Liz. Will I suddenly believe in God? That might not be a bad thing at this moment. What do you believe in anyway? Maybe I should know this before I sign on the dotted line.”

She's never asked me this before. It's not an easy question to answer, but this would be a good time to try.

I told her what I don't believe first. I don't believe our brains can fully fathom God, or come up with ironclad answers to the big questions - like who are we and why are we and where did we come from and where do we go?

We can't think our way through any of those questions. We can try. I love the way we try - science, art, religion, wine, mountain climbing, whatever. But so far, no one has definitively answered anything. So I said to Maggie, “When I pray, I pray to just settle down and trust the mystery. Prayer for me is relaxing into the mystery.”

“Really? That's what prayer is?”

“Well, maybe not for everybody, but it's not my business how other people pray. To me, prayer is letting go of fear and relaxing into the vast, eternal mystery. I don't care what you call that mystery - God, consciousness, universe, spirit. Those are all made-up names for the unnamable.

“All I know is there's nothing better than that wide-open, opinion-busting, all-things-are-possible, everything's-OK feeling of prayer.”

What I want to say but I don't, because it's probably not the right time, is this: “Who knows, Maggie, if you decide to forgo the transplant, maybe you're the lucky one - maybe you're being called out of this world for glorious reasons, leaving us fools behind to slog our way through another day.

“Maybe it's not a tragedy for your kids. Maybe they'll spin their grief into strength, maybe you will help them flourish from the other world. Or maybe you'll choose to go ahead with the transplant and you'll outlive us all and prove that miracles are possible.

“Maybe this is all happening for you to finally stop doubting yourself and to step boldly into who you always were meant to be. Maybe you'll become a world-renowned artist, or you'll wander away and become a monk. We just don't know.

“That's what I believe,” I told her. “I believe we dwell in mystery, and although that mystery often seems to suck, when I pray, I wake up, and I know that it's all for something, that nothing is wasted, and it's all good.”

Now we're here in the examining room, and I'm taking deep breaths and calling on that mystery as we wait for Maggie to make up her mind. “What's it going to be, young lady?” the doctor asks, putting his hand on Maggie's shoulder. “Shall we prepare for transplant?”

And without missing a beat, Maggie looks around the room at us, her motley team, takes a sharp breath in, and says, “OK, let's do it.”

We drive away from the hospital. It's one of those early New England spring days that can't make up its mind. It's raining in the parking lot, but by the time we get onto the highway it's snowing. I am driving; Maggie is stretched out in the back.

I turn my head and ask, “How are you doing?”

“Shhh,” she says, putting her finger to her lips and closing her eyes. “Shhh, I'm relaxing into the mystery.”