BRATTLEBORO — Diane Eickhoff, the author of Revolutionary Heart: The Life of Clarina Nichols and the Pioneering Crusade for Women's Rights, took exception to the historical column I wrote about Clarina Howard Nichols. Her recent Counterpoint leads readers into some inaccuracies that I feel are important to address.

Eickhoff's response gives the incorrect impression that Nichols' attitudes toward indigenous people have been fully examined and that she has universally been found to be benign by historians. As partial evidence of Nichols' lack of bigotry, Eickhoff points out Nichols' son's marriage to a Wyandotte woman.

In reality, as noted in the other great historical biography of Nichols, Frontier Feminist, by Marilyn S. Blackwell and Kristen T. Oertel, Nichols' attitudes toward indigenous people while she was in Kansas were complex (as I noted that they were during her time in Brattleboro).

“Beyond the obvious racism that even reform-minded whites possessed” Blackwell and Oertel write, “Nichols's opinion of the local tribes was based in part on their degree of conversion to Christianity and on their adoption of white middle-class values, all measures of their ability to adapt to the enlightened civilization she envisioned in Kansas.”

Blackwell and Oertel also note that ”the underbelly of her expansionist worldview was a general disregard for the displacement of Native American peoples and cultures,” but eventually she “softened her ethnocentrism with womanly sympathy.”

My column offers some evidence that this “softening” may have started before Nichols left for Kansas. (New research, which I will add to the spreadsheet I provided, shows she was, at the least, not entirely supportive of “manifest destiny.”)

* * *

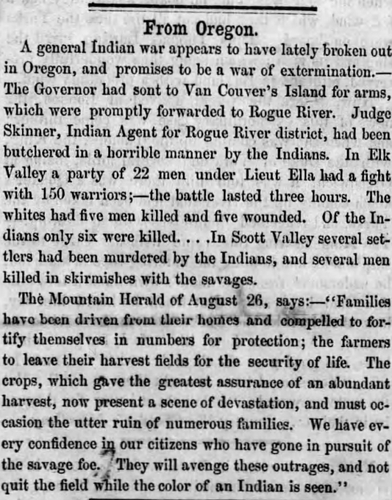

Eickhoff also attempts to cast doubt on the nature of the decision to publish one item on Oct. 12, 1853 - and whether Nichols even had any part in that publication.

The item has two parts: a summary of the news, and then a quote from The Mountain Herald.

The summary promotes racial hatred, using as it does the word “savage” and an entirely one-sided and inflammatory narrative of violence.

Nichols was a gifted writer, and it seems incredibly unlikely that she would not have understood the harmful potential of the summary, paired with the quote from the Herald.

Writing about her own editorship and using the editorial “we,” Nichols said in her newspaper's July 16, 1851 edition: “We are not less identified with the editorial conduct of the Democrat than we have been for years. All its editorials are from our pen [...].”

Eickhoff's notion - that because Clarina Nichols was not in Brattleboro in October of 1853, she categorically could not have dictated the editorial content of the Oct. 12 paper because she was in Wisconsin - is mistaken.

The author cites as evidence two pieces written by Nichols in that issue as proof she was not in Brattleboro to edit the material I quoted. But it appears to me that this very same material could also be evidence of Nichols' continued ability to transmit content to the paper, even from afar, or to compose it in advance of her departure.

It is important to understand the nature of newspaper composition in the 1850s. The Democrat, like other newspapers of the era, contains old speeches from politicians, literary extracts from Dickens, poems, and items gathered from around the world via telegraph and mail. Few if any of the items in the newspaper, especially in rural settings, contain what we call “news” that could not be set up well in advance of publication.

In Nichols' time, editors used the telegraph (which was in Brattleboro by 1851), newspapers, and the U.S. Postal Service to gather and send news.

That said, Eickhoff does point out in her book that she left Brattleboro for her trip to Wisconsin with her husband's blessing - and that his two grown daughters, printers in their own right, were poised to help in her absence.

And her book does describe Nichols' grueling schedule of lecturing and traveling - a schedule that contributed to her and her husband's decision to close the newspaper.

But even if Eickhoff is right in assuming that this item and its summary were not selected by Clarina Nichols, I stand by my larger point and, indeed, the purpose for writing the column in the first place.

* * *

Whether Nichols herself or someone else advocated for genocide in the pages of her newspaper, the publication of those ideas was not a mere cataloging of random opinions found in newspapers across the country, it was promotion of harm.

It is also only one of several inflammatory articles published during her tenure as editor. I believe that evidence shows Nichols' unfortunate repeated contribution to the promotion of genocide, which was not uncommon for editors of her era.

In my column, I didn't fully explain the larger point of why I included details of my wedding on the banks of the West River. Let me return to that in explaining my larger point.

As my wife Cynthia and I paddled away in a canoe from the wedding spot, I had the joyous feeling that the West River was somehow mine. Yet I was mistaken. In reality, we are all living on Abenaki land. My home in Brattleboro is built on a former river terrace. Who knows the full history of “my yard”?

Denial of both the potential and real harm done to indigenous people - whether in the form of feelings I indulged in my canoe and expressed to friends afterward, or in the form of items published in a newspaper in the 1850s - does not take us anywhere good as a community.

We are more fully human when our compassion expands outwards toward all people - and we should do so for the brief time we are alive. I believe that is an absolute that transcends the social norms we are born into.

It is harmful to history to diminish the nature of this type of reprint, which was practiced by many other editors across the country. And it is out of respect to all the formidable accomplishments of Clarina Howard Nichols - with her progressive empathy toward enslaved people and her righteous anger toward the disenfranchisement of women - that these views toward Native Americans stand out in starker contrast than they otherwise might.

For 150 years, biographers of Thomas Jefferson similarly made vigorous denials of his relationship with Sally Hemings, a relationship that, if acknowledged, would complicate, cheapen, and diminish the founder's intellectual and moral legacy, much as Eickhoff says I've done with Nichols.

History - and compassion toward Hemings' descendents - eventually won out over denialism on that score.

History benefits the most from differing perspectives expressed with civility, and I hope Eickhoff will continue to offer hers, either in these pages or at forthcoming community conversations about Clarina Nichols, that are being planned by the Words Project for Dec. 12.

As I did originally, I encourage people to purchase Eickhoff's book, not only because it is well written, but also because it has so much valuable information about an amazing person who shaped our town, our state, and our nation - in so many ways for the good.

But no single book or biography can ever hope to cover all aspects of a legacy. And no heroes and heroines are without flaws, contradictions, and even beliefs that are deeply grooved by the social norms of their times. Only universal compassion can save them, and us, from falling into those grooves repeatedly.