WESTMINSTER WEST — My high school in Miami was comprised of two-thirds white kids and a third black, with a few Hispanics. It was the late 1960s, the era of school busing, with plenty of racial tension, and a good bit of turbulence on the streets and in the schools.

At such a time, our school was noteworthy for its almost total absence of overt hostility. We prided ourselves on the appearance of good will and respect among ourselves.

Well ... we white kids prided ourselves, making naive assumptions about the general nature of things.

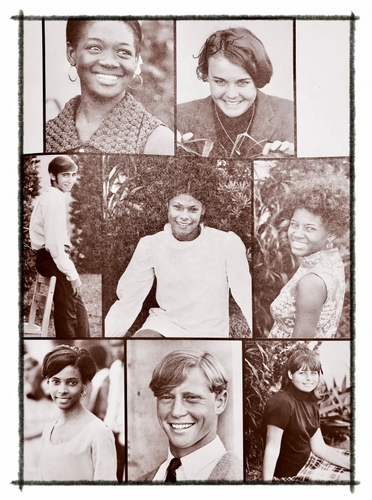

During high school all the organizations, teams, and classes were fully integrated. It wasn't like the only popular kids and high achievers were white. I could cite myriad illustrations of racially mixed service clubs, the cheerleading squad, winners of the senior superlative awards, basketball heroes, bright lights in the marching band.

But in the years after graduation, bewildered by how our class reunions came in the form of segregated events, we'd need to open our eyes to a larger truth about the presumed “we” of the student body.

The outer appearance of things is not what this is about.

* * *

In my class, I was one of six Fraziers. The other five were Sylvia, Curtis, Gloria, Barbara, and a second Barbara. I alone among the Fraziers was pale-complected.

Every now and again, one of my white classmates - likely a boy, one who (like me) got good grades and fancied himself open-minded and politically liberal - would draw me aside and mutter something.

Sometimes, it was about one or another of our dark-skinned Frazier classmates being “a family member” of mine. Sometimes it was about my being related to Joe Frazier, the boxing giant. These quips were intended to get an embarrassed laugh out of me, to elicit a playful jab in the ribs. All in good fun.

These same boys had black friends, guys they bantered with in the halls, played sports with.

My typical outward response to those tiresome attempts at humor was a wordless facial expression indicating I didn't find the comment entertaining. I left it at that.

It was all very subtle, the dynamic of what went on.

When I look back now on those experiences, I see how the way I limited my response to raised eyebrows and a mouth curled in disdain was symptomatic of my own racial conflict and cowardice.

It was illustrative of a more pervasive pattern. I was too timid to open my mouth and take my classmate to task, pressing him to look at what must underlie his remark, enabling the two of us get into it, maybe, in a way that doubtless would have had us both squirming with discomfort and avoidance.

Had I been willing to say something, maybe at least one of us could have been led to confront our own messy interiors - to see we were very much a part of the systemic injustice that would eventually result in separate reunions.

* * *

The fact that these experiences are still with me, 50 years later, speaks volumes. Even back then, something in me sensed that beneath the dismissal of the boys' “jokes” must lurk my own issues. My enduring cowardice - to face myself, to confront another - carried on for years, in myriad settings.

Open-minded and well-meaning as I fancied myself, there always was the timidity, the hesitancy to take a stand or to risk rocking the boat.

I could say it was somebody else's boat, but of course it was more truly my own.

For as much as a seed of moral integrity might have been struggling to take root in my youth, the more potent force was the need for approval, to adhere to societal norms.

Which kept me not only from standing up and speaking out when that was called for in those turbulent times, but also from confronting my deeply buried conflicts, the darkness where uncomfortable truths struggled to keep their heads in the sand.

* * *

Meanwhile, my parents and I argued over their attempts to “protect” me from possible harm - like the time they said my (white) boyfriend and I could not double-date with black friends of his, lest someone see us all in the car together and pick a fight.

Righteously, I accused them of racial intolerance, as if I were entirely “on the other side” of things.

During my sophomore year, Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered. In the despair-filled days afterward, my black schoolmates launched the idea of our school being renamed in his honor.

I remember viscerally my reflexive discomfort at the prospect of my school being named after him. Clearly, King had been worthy of great admiration, a righteous and galvanizing leader in the fight for equality. But ... well, he was ... black.

I scrambled to somehow “justify” this undeniable bias. How my buried conscience strained to avoid the ugly truth. I suspected some grim recognition underlay my discomfort.

Which is, of course, why it's stayed with me, all these decades. And why it revisits me now in present-tense America.

Does it go without saying that - given the white-majority student body and staff (however “liberated”) - our school kept the name it had always had? Nor do I imagine any of the black students being surprised at the outcome.

Same old, same old.

* * *

I could not tell myself the fuller truth - not in my teens, and not for most of the time since.

Like so many, I averted my eyes from the moral hypocrisy, unwilling to examine how I was contributing to the very societal problems I outwardly abhorred. I couldn't see the power of silence and inaction, let alone face how not rocking the boat sustained my own comfortable life, to the manifest detriment of others.

And so I managed to postpone, for the ten-thousandth time - along with nearly every other privileged and well-meaning person in our democracy - the probing of my own role in upholding the inequality and injustice we are now being collectively forced to confront.

Only now, there's some indication that a more widespread reckoning may be occurring, having the potential to bring about material change.

In this time of mounting despair, there seems to be an increasing willingness for some of us to confront our comfortable selves, to risk engaging in authentic exchange with others.

To second-guess our enduring assumptions.

To make meaningful reparations for the centuries of systemic inequity, shaking up institutions that have long needed shaking up.

May it be so.