PUTNEY — In July, The Washington Post estimated that, as president, Donald J. Trump has told more than 20,000 lies. In a press conference on Aug. 8, Trump betrayed the truth yet again and he got called on it.

The president gloated about his administration having passed the Veterans Choice Act, a piece of legislation that made it possible for veterans to use their government health benefits at providers other than VA hospitals. In reality, it was signed into law by former President Barack Obama.

Trump's press conference that day was held in Bedminster, New Jersey, at his golf club.

“I've just signed two bills that are great for our vets,” Trump announced to the crowd, which included members of the golf club, which The Real Deal estimates that it costs $350,000 to join.

“Our vets are very special. We passed Choice, as you know, Veterans Choice, and Veterans Accountability. They've been trying to get that passed for decades and decades and decades, and no president has ever been able to do it. And we got it done [...].”

“Why do you keep saying you passed Veterans Choice?” called out CBS News correspondent Paula Reid.

When Trump ignored her and tried to call on another reporter, members of the golf club cheered loudly.

Reid tried again: “You said that you passed Veterans Choice. It was passed in 2014.”

Her question was inaudible because of more cheers, but she ended with, “But it was a false statement, sir.”

The new round of cronies' cheers had nearly drowned her out. Trump seemed to recognize the commotion as an opportunity for him to escape a tough moment to buoyant sounds. He walked off the stage to the opening notes of the Village People's bubbly disco hit “YMCA,” which the band's co-founder has asked him not to play.

Reid gets plenty of points for her insistence. According to CNN, she may be the first reporter to challenge Trump's alternate fact about that particular act. That alone is remarkable, considering CNN estimates Trump has claimed credit for the Veterans Choice Act 150 times.

Why haven't reporters routinely challenged Trump on this claim? Why didn't his loyalists take issue with his declaration a few days later that former Vice President Joe Biden will “hurt the Bible, hurt God”? Why does any American believe Trump about anything, given that his lies rain like a plague of frogs from heaven?

* * *

One answer may be that it is part of human nature to embrace as possible ideas that are clearly improbable.

How else to explain children's belief that a big, round man can slip down their chimneys on Christmas Eve?

Or Catholics' belief that, more than 2,000 years ago, a virgin gave birth to a boy whom, all these years after his death, people “eat” in ritual gatherings?

What about the Mormon idea that the as-yet-undiscovered planet Kolob is the single star geographically closest to God's throne?

What about the smokers who discount the odds that tobacco can kill them?

What about the people who believe that, even though face masks stop the spread of the droplets that carry SARS-CoV-2, masks won't stop the spread of the disease the coronavirus causes?

* * *

Psychologists credit common, unconscious, cognitive tricks for people's ability to perform the psychological jujutsu necessary to temporarily misplace their reason.

• Cognitive dissonance describes the psychological distress caused by trying to consider as true two very inconsistent statements. For example, “Trump always tells it like it is” is psychologically inconsistent with “Trump has repeatedly lied about signing the Veterans Choice Act.”

To rid themselves of the discomfort caused by the dissonance, people either toss out one of the pieces of information or interpret one or both in a new way. “Trump has repeatedly lied” might get tossed, in which case “Trump always tells it like it is” can stay.

• Confirmation bias (a.k.a. “my-side bias”) describes people's reluctance even to take into consideration information that is discordant with their beliefs. When they are cognitively biased, people welcome only intelligence that tells them they've been right all along.

These two concepts by no means constitute an exhaustive list of the ways people fool themselves. By and large, they can be grouped under the rubric motivated reasoning, which means constructing and evaluating arguments in ways that bring about a preferred conclusion.

Motivated reasoning assures people that they are fundamentally in command of important facts. That in and of itself comes with such a huge, energy-saving upside that it may be coded into human DNA.

Early humans who relied on motivated reasoning wouldn't have needed to hide every single time they saw a swaying blade of savanna grass. They might instead have assured themselves, for example, that “nah, lions don't hunt at noon” and gone about gathering roots, which they needed to do lest they starve.

As useful as motivated reasoning may always have been to humans, in the modern world it can easily lead voters far afield from the truth. This can happen to the great satisfaction of politicians who lie.

Which, of course, many do.

* * *

As Daniel Ellsberg's Pentagon Papers revealed, former President Richard Nixon lied to conceal the late-1960s “secret war” in Cambodia and Laos. Nixon also lied when claiming he had nothing to do with the cover-up of the Watergate break-in.

And former President George H. W. Bush's lie that he deployed troops to the Gulf in 1990 to “assist Saudi Arabia in the defense of its homeland” was revealed when a St. Petersburg Times reporter obtained a satellite photo showing only an empty desert where the White House claimed 250,000 Iraqi troops and 1,500 tanks were swarming.

Those lies cost hundreds of thousands of lives. Even so, they represent a time when lies seemed, well, more reliable than they do now.

According to Jason Stanley, a professor of philosophy at Yale University and author of the 2018 book How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them, the fascist political playbook calls for lies of a different sort than American politicians typically use.

Where Bush and Nixon lied to conceal what they'd done and why, fascist politicians also use lies to convince a susceptible population that they are exceptional and that other nations, religions, or races are holding them back from glorious destinies.

Fascist politicians then create an entirely new reality that matches the lie. For example, Adolf Hitler bathed his Christian followers in Poland in tales of how superior they were to the Jews, who he said were filthy and homeless and conspiring to keep Christians from the future they deserved.

Then, he took away the homes of Warsaw's Jews and crowded them into a ghetto, where he starved them. As they died dirty and homeless in the streets, he sent documentary crews. The images of emaciated Jews in tattered clothing expiring here and there made them as a group look scary to Hitler's Christian followers in precisely the way Hitler wanted.

In a conversation regarding the current Trump presidential campaign, Stanley pointed out ways in which our president leans on some of Hitler's rhetorical tricks.

Trump pits ethnicities and racial groups against each other. He implies that people of his own heritage (white) deserve more than they're currently getting, and he claims that certain villains (immigrants) are standing in their way.

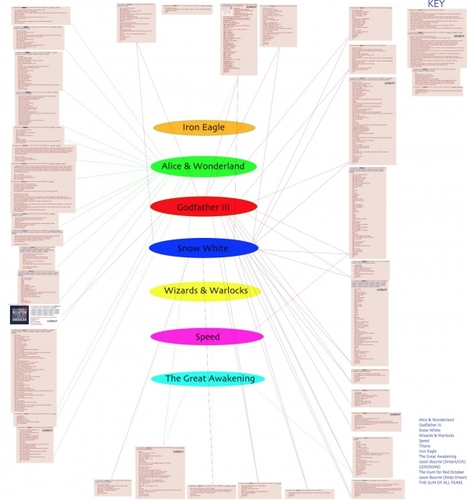

And if he's not directly abetting QAnon's “deep state” stories of conspiracies by shadowy figures, elites, Jews, and even the Elders of Zion against Trump and his supporters, he's not adequately discounting them.

Trump also lies in a particularly unusual way, according to Stanley.

“When he says truly preposterous things, Trump isn't trying to deceive us. He's not offering reasonable beliefs like George W. Bush's 'there are weapons of mass destruction in Iraq' that he hopes we'll latch onto. He's just showing off how ludicrous he dares to be,” Stanley said.

“His supporters love it when he says ridiculously untrue things that he assumes they won't believe,” he continued. “Really, the more outlandish Trump can be with some of his lies, the more fun his followers have listening to him. He seems like a winner, and they want to be on the winning side.”

Mexico will pay for the wall. Windmills cause cancer. The coronavirus is a Democratic hoax.

They all make sense - if not as truths, then as political feints.

* * *

On May 26, 2016, Trump told a crowd in Billings, Montana, “We're going to win. We're going to win so much. We're going to win at trade, we're going to win at the border. We're going to win so much, you're going to be so sick and tired of winning, you're going to come to me and go, 'Please, please, we can't win anymore.' You've heard this one. You'll say, 'Please, Mr. President, we beg you, sir, we don't want to win anymore. It's too much. It's not fair to everybody else.'”

Now, almost four years later, the Pew Research Center has announced evidence that Americans may indeed be getting sick, if not of winning, at least of Trump.

On March 5, 2020, Pew released the results of a survey conducted in early February, well before the coronavirus emergency descended on the country and the emptiness of Trump's showboating became fatally apparent.

In those pre-pandemic weeks, only about one third of Republicans and 15 percent of Americans responding to the Pew survey said they approved of Trump's “conduct.”

Then, in a Quinnipiac poll published on July 15 (well into the pandemic), two thirds of survey participants said they didn't trust information Trump gave about the coronavirus, though they did trust Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. What happened to turning the volume down on joy born of buffoonery?

* * *

It probably wasn't the strength of Democrats' rational arguments.

First of all, Trump hadn't really been telling plausible lies with which to argue. But even if he had, hundreds of university studies have shown the cognitive tricks people use to help them defend their beliefs are often strong enough to withstand even the most artful lines of reasoning.

For example, in a 2017 study about the effectiveness of logical arguments, researchers at the Slovak Academy of Sciences didn't try to change minds about the highly emotional topic of abortion. They merely showed study participants several series of three-sentence syllogisms; two propositions were always followed by a logical conclusion.

One was: “All dogs are mammals. Some carnivores are dogs. Some carnivores are mammals.” Another: “All human beings should be protected. Some foetuses should be protected. Some foetuses are human beings.”

That logical conclusion is not, strictly speaking, an argument for or against abortion. Even so, the researchers encountered so much resistance from people emotionally invested in the issue that they couldn't get a statistically significant number of them to acknowledge the neutral logic that the foetus sequence builds.

Another example: In a 1979 Stanford University study, researchers exposed participants who supported the idea of capital punishment to rational arguments against it, and they exposed participants who were against the idea of capital punishment to arguments in favor of it.

Rather than change their minds, by and large, participants became more entrenched in their original attitudes. This digging-in-of-heels has happened in so many studies that researchers call it the “backfire effect.”

With the election approaching, many people who see a fascist tint in Trump's eyes are beginning to scramble for ways to counter whatever appeal he has left.

When asked by phone about potential practical approaches they might use, Stanley offered “local journalism” as one possible answer.

“When people see on their local news that their neighbors' crops are dying, they may object to Trump's climate policies,” he said. “When they see in the local paper that the police budget dwarfs the school budget and the rest of the town's budget.... Well, local news matters.”

* * *

Meanwhile, some activists are employing a get-out-the-vote method called “deep canvassing.”

Resigned to the fact that rhetoric isn't going to sway Trump supporters from firmly held positions, deep canvassers approach infrequent and swing voters to talk not about issues but about friends, family, and core values.

The canvassers divulge personal stories revealing the motivations behind their own political preferences and encourage voters to share their stories. In the conversations that ensue, canvassers respond to voters' expressions of appreciation for decency and kindness by observing that such vital qualities are not apparent in Trump's lies and divisiveness.

The fundamental message that deep canvassers convey is that a vote for Trump works against what the voter has said they cherish most.

Does deep canvassing work? A small 2016 study published in Science Magazine found that 56 canvassers helped Miami voters shift their attitudes about transgender people in a way that held true for three months.

* * *

And from the field of research into conspiracy theories, there is some indication that just talking to people about their ideals may direct them away from endorsing extreme views.

In a study published in Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin in January, social psychologist Kai-Tak Poon of the University of Hong Kong investigated why some people endorse conspiracy theories and why others do not.

First, in a series of three experiments, Poon and his team demonstrated that people who feel socially ostracized are more likely than others to endorse conspiracy theories. Then, the team engaged 174 people in a fourth experiment. They asked participants to immerse themselves in feelings of social rejection, after which some of them were invited to describe their core values and to talk about why those values were important to them.

The researchers found that participants who'd been given a chance to verbally affirm matters about which they deeply cared were less likely than others to fall prey to ideas about dark actors working secretly behind the scenes to create mayhem.

* * *

Given these early signs that openhearted conversation may have a politically moderating effect, should Americans take to the streets - not in protest, but to chat with their neighbors about what's important to them?

Would that be a valuable contribution to the democratic process? What if knocks on the door or phone calls frighten people? What if almost everyone is by now too afraid to speak openly?

Maybe gently starting those conversations anyway would be the kind of “good trouble” civil rights leader Rep. John Lewis wrote about in an essay published on the day of his funeral.

“Ordinary people with extraordinary vision can redeem the soul of America by getting in what I call good trouble, necessary trouble,” he wrote. “Voting and participating in the democratic process are key. The vote is the most powerful nonviolent change agent you have in a democratic society. You must use it because it is not guaranteed. You can lose it.”

We can't argue people away from their convictions. But if we can talk to them, maybe they can think a little more mildly, and then vote.