WESTMINSTER — My father is dying.

I sit with his 95-year-old body as it, moment to moment, lets go.

He had a difficult life, suffered from reckless parenting when he was young, was very poor, was without food and housing in his teens, navigated the first 45 years of his life with no ability to read or write.

As an adult, he often lost his job. He was turbulent and violent.

On the other hand, he lived a long life with a wife and three children who navigated his disturbances as best as possible. Overall, his adult life was handled mercifully, and his dying stands out to me as relatively peaceful.

If I think only of him or myself, I could give over to a feeling of gratefulness and resolution.

But there are things I have been learning about race and the history of the United States and about my father's ancestry, also, that complicates my experience.

* * *

At the turn of the century, my father's grandparents emigrated from Buccino, Italy to Altoona, Pennsylvania, where many people from their town were recruited for their masonry talents to build tunnels and bridges for the railroad.

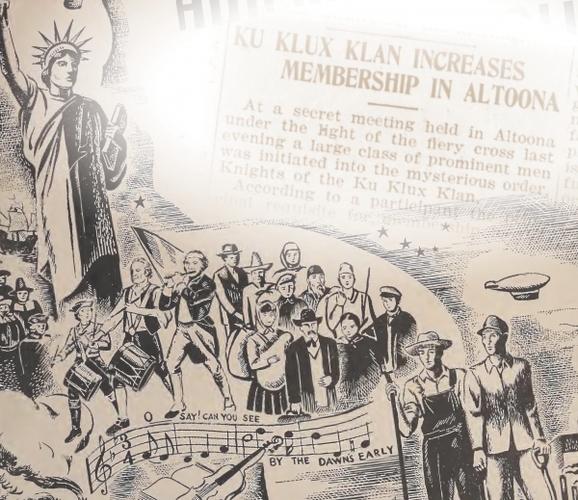

This turn-of-the-century influx of Italians and other Southern and Eastern European immigrants, as well as African Americans coming north in an attempt to escape the brutality of the Jim Crow South, were greeted with vitriol and cruelty.

White supremacist values were woven through Protestant American society.

The Ku Klux Klan, having waned in the South, traveled north to states like Pennsylvania. They quickly rallied 250,000 Pennsylvania citizens, both men and women, to join their ranks.

By the mid-1920s, Altoona had the distinction of being the Pennsylvania city with the highest population of Klan members per capita than anywhere in the United States.

The Klan's anti-Black, anti-Catholic, and anti-Jewish platform gained fierce participation from many Pennsylvanians, from their Protestant churches, political institutions, police forces, and businesses.

Many Pennsylvanians who were not members were sympathizers. As a result, there was ghettoization, intimidation, exclusion, and death in the life of immigrants in the state and across the U.S.

* * *

As the late 1920s came to a close, the number of Ku Klux Klan members began to fade in Pennsylvania, partially the result of KKK and white supremacist corruption and infighting.

In addition, the Immigration Act of 1924 (the Johnson-Reed Act), signed by Calvin Coolidge, severely limited immigration from Eastern and Southern European countries into the U.S., drastically cutting off the flow of immigrants.

In the 1930s, however, white supremacists and the remaining KKK joined forces with Italian and German immigrants who were moved by the fascist, white-supremacist platforms that Mussolini and Hitler were driving into the world. Many Pennsylvanians formerly at odds found common ground in another wave of anti-Semitic, anti-Black fervor.

I do not know what side my immigrant relatives chose in those days.

* * *

So, as I sit with my father, it becomes clear how I, his child, find myself a homeowner and a professional. How I have been able to lift myself out of the lower-class childhood I grew up in and become a parent who can effectively advocate for my children.

And it becomes clear how I am able to attend to my parents' needs, like now, with my father so well looked after, comfortably cared for and with good medical attention, in a system my siblings and I have chosen.

Yes, I worked hard, and yes, I am resilient, but I didn't work harder and am not more resilient than many people growing up in poverty.

I certainly didn't stay out of trouble. But I was never jailed. I didn't always make healthy choices, but people and institutions didn't relentlessly push me down, particularly once I became a young adult.

This has everything to do with whiteness.

All I have achieved or have been given depends upon the fact that the Italians, who were vilified and excluded with other immigrants in the early 1920s, gradually gained the identity of whiteness and subsequent access to all the privileges whiteness offers.

I don't know whether my relatives fought the KKK, as some Italians did, or whether they joined the fascist Black Shirts movement and took up attitudes and arms along with other white supremacists.

Regardless, I know what they, and what I, gained based on the actions of those Italian immigrants who did step into the white supremacy movement.

I understand that my entry into a life of owning a home and raising children in an overwhelmingly white town in Vermont was gained at the cost of many other people.

I remember my father's family openly and confidently speaking about African American and Jewish people derogatorily, despite the fact that my mother, his wife, was Jewish.

I look at this care facility my father is dying in, its residents all white, its nurses and other providers on the floor almost all people of color, and its administrators, all white. I think of the violent racism and anti-Semitism I grew up being punished with and surrounded by.

I draw lines between all these things. The racist and xenophobic words of Donald Trump. Police brutality. None of this can be considered new for the United States.

I listen to my father's regular but fading breathing and find myself considering other, less peaceful deaths - lynchings, beatings, burnings - that my father and I, because our skin is considered white, have not lived in fear of.

I find myself moved to read and research, literally here at his bedside, to understand the real history that is my family and my country, the United States.

* * *

My father's passing is painful. It is an important event in my life.

But it is not sufficient to experience the sadness, the loss I feel, and even the relief that is coming, as personal.

If I believe that racism at an individual or institutional level is wrong, which I do, I must, at the same time I sit beside my father's fading body, think about others and think critically about the social and historical context in which I live, in which he dies.

This, I believe, is what it will take to move our country forward, beyond its deeply racist roots.

To be able to feel my own pain but leave room beside my discomfort to realize the greater losses due to racism and oppression that other people contend with.

To give that reality space in my attention even as my own life suffers loss.

To want my father's life to be valued but to let go of the privilege of having my father or his passing or myself or even my own children to seem singularly important.

In order to accept the reality that has been and is our world, white people need to yield comfort. And we cannot use discomfort or personal pain as an excuse for not helping to be aware of and change circumstances that have benefited us at the cost of others.

At times when something of personal importance is taking place, like this moment for my father and my family and me, we need to remember to consider and act on issues of equal or greater importance outside our sphere of immediate experience.

I hold my father's hand and I think of his passage from this life, but I also consider our more comprehensive history of race and white privilege. Confronting this knowledge is the means I have right now of discontinuing my complicity with oppression.

* * *

Frank Pucciarello died March 13, 2021 at 4:11 p.m.