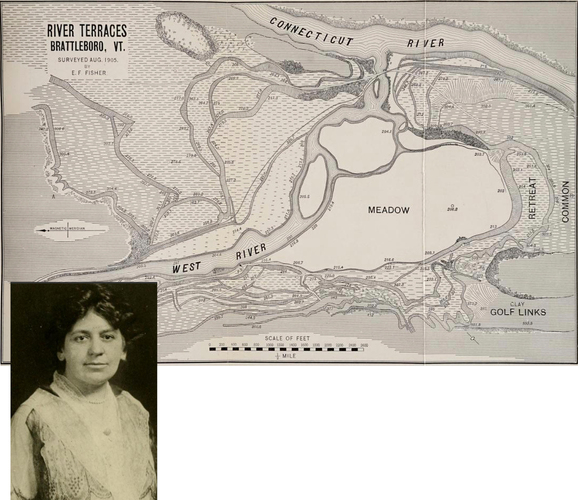

EAST DUMMERSTON — In the summer of 1905, a young woman might have been spied clambering up and over the many flat terraces along the West River where it joins the Connecticut, in the area known today as the Retreat Meadows.

Each terrace represents a former position of the West River; she was working out that history as a test of a new theory on the formation of such terraces.

What Elizabeth Florette Fisher was doing was most unusual. Field geologists were few in America; fewer still were women. Her work was published in 1905; she presented copies to the Brattleboro Free Library, now Brooks Memorial Library.

You can go there and read the paper, with her signature on the cover. You will see that it includes a series of meticulous maps that show the location of the West River at the times of the formation of each terrace. If you go to look at the kiosk at the boat landing on Route 30, you will recognize one of those historic maps in use as the backdrop of another history - that of use by the Abenaki people.

One hundred years ago, the prospects for a woman scientist were severely limited. Among women geologists, the horizon was so restricted as to give rise to a stereotype - that a woman geologist would publish a single scholarly paper and then disappear into a women's college.

The large universities hired only male teachers, and women's colleges could not command the kind of funds to carry on scholarly research. Thus, no publications were forthcoming.

* * *

The early trajectory of Elizabeth Fisher's career seemed to be fitting that stereotype faithfully. She published the paper on the West River terraces and went off to teach at Wellesley College. She never did publish another geologic study.

Instead, she trained generations of students.

She took them out into the field, including a camping and horseback trip for 12 students to Glacier National Park; that trip, in 1920, has achieved the status of legend at Wellesley. This showed them that women could do geologic field research.

She instituted and taught a course on conservation of natural resources, which gained such renown that she was contracted to teach it as a series of lectures at Harvard and at the Council of National Defense, a World War I organization tasked with the utilization of resources for the war effort.

A scholarship in Fisher's name - given annually to a senior who was going on to graduate work in geology or a related subject - is still given out each year.

The society section of The Boston Herald reported that she chaperoned a group of students to attend the Harvard-Princeton football game in November of 1906. She must have been beloved of her students.

It doesn't sound much like a “disappearance.”

* * *

Fisher's conservation work led to a textbook, Resources and Industries of the United States, published in 1919. Its intended audience was junior high school students in geography classes. The book went through two editions, suggesting some success; the second was published 100 years ago this year.

In her choice of illustrations, Fisher seems to betray a continuing fondness for our little town.

Imagine the book being handed out for the first time. One student, idly flipping the pages, suddenly stops.

“Hey, look! Here's a picture of Brattleboro! It's about haying. It looks like the field by the West River!”

Another photo, illustrating maple sugaring, is identified as from Brattleboro. A third Brattleboro photo shows garden vegetables at market. Three photographs of tiny Brattleboro in a book meant for nationwide use.

Fisher did not intend the book to be merely a compendium of facts and figures. Yes, she does have the facts and figures of the resources and their importance, but she uses them, as she wrote in the book's preface, “to show the urgent necessity for the conservation of these resources in view of the complete dependence of our industries upon them.”

She wrote a textbook that did not simply report; it advocated.

Elizabeth Fisher became known as a conservationist, one of a small band who were challenging the idea, prevalent at the time, that the resources of this continent were infinite and therefore need not be cautiously used.

* * *

However.

Almost the first thing Fisher covers is “the watering of dry lands,” where she rhapsodizes about the gigantic projects to irrigate the arid southwest, followed directly by “the draining of wet lands,” where she describes approvingly the ditching and draining of eastern swamps to get at the rich black accumulation of soil under the water. (Elsewhere, she made proposals - based on her field work there - for the near-total draining of the Everglades for sugar cane.)

This policy could be summarized as “drain every swamp; water every desert.” Not the sort of policy we would associate with a conservationist view today - not even close. Not even, it would appear, consistent with her own admonition for cautious and careful use of resources.

And yet she became known as a conservationist. Perhaps it meant something different in those days to be called a “conservationist”?

Or perhaps not: there was, then, a tension between those whose goal was to discontinue the use of natural resources (“preservationists”; thanks to them, we have a system of national parks) and those who saw a need to use the resources, but with great care (“conservationists”; that is where Fisher stood).

That tension exists today.

* * *

Elizabeth Fisher saw great value in those resources, first, for increasing productivity. She writes, “By hand labor the individual farmer would be fifteen years in growing for the market an amount of wheat which by the aid of machinery he could produce in one year.”

Second, those resources can reduce human drudgery: In the coal industry, “breaker boys” picked rocks out from coal passing by on a constantly moving conveyor.

“All day long they sit picking the rock from the coal,” she writes. “Their fingers become cut and sore from the sharp edges of the moving coal and rock, and stiff with cold. Rest is out of the question because the overseer is constantly watching.”

This description is accompanied by a chilling photo, complete with the overseer. Imagine the effect that must have had on students of the same age, sitting comfortably and warm in the classroom; surely, they must have seen the value of mechanizing that work, so those kids in the coal country could be free from that toil and go to school, too.

With the case made for mechanization, the critical value of the resources for those machines is evident, as is the situation: the resources are vital; they are not infinite; therefore, they must be used carefully and wisely. Thus, Fisher made her conservationist case.

But what of her advocacy of draining and irrigating? How does that fit into her message of wise use?

Well, to Fisher, land and soil are natural resources, like coal, oil, wood, and all other resources, and therefore must be used wisely. To allow land to lie unused when it could be drained or watered was wasteful; underuse was as bad as overuse.

Today's conservationists would probably not agree, but it is consistent with her view of things.

* * *

There is a cruel irony in this story of Elizabeth Florette Fisher, geologist and conservationist.

Among her pioneering efforts, she was the first (or at least, one of the first; sources differ) woman geologist to be hired by an oil company to do geologic field mapping in the search for oil.

Into the field she went - a familiar place for her - and spent the summer of 1918 surveying what became known as the Ranger oil field, in north-central Texas.

That field turned out to be the largest oil field then known in the United States; through a combination of overzealous drilling and wasteful practices, that huge field was totally depleted and abandoned in just four years.

Its name became synonymous with the wanton waste of natural resources.