BELLOWS FALLS — During the first week of August, Great River Hydro, which owns the hydropower dam on the Connecticut River between Bellows Falls and North Walpole, New Hampshire, began a drawdown of the river upstream of the dam in order to repair one of the dam's spillways, damaged during the July 10–11 flood.

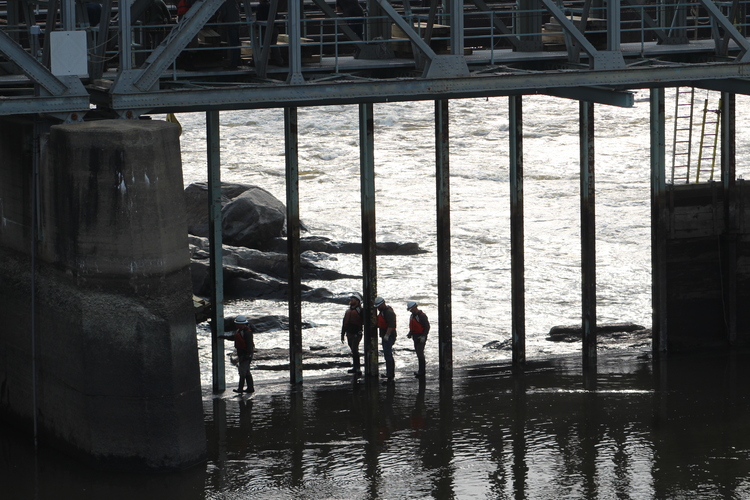

The low water revealed what is left of the series of more than a dozen stone piers on the bottom of the main river channel, upriver from the dam.

The piers, which when in use were quite a bit higher, were a surprise historic reminder of the important role the Connecticut River and the small river towns of Bellows Falls and North Walpole played in what were the oldest and longest river log drives in the history of the United States.

Four of the piers were clearly visible in a line a few hundred yards upstream near the Joy Wah Restaurant, and another was revealed a few miles north at Herricks Cove, near where the Williams River enters the Connecticut.

By the afternoon of Thursday, Aug. 4, the spillway was repaired and water levels were on the rise and, by Friday morning, the river and the dam had returned to normal.

But the day before, water levels behind the dam reached the lowest levels in living memory. The workers repairing the dam, and the once-in-a-lifetime views of the riverbed, drew nearly as much public interest as did the July floodwaters as onlookers got to see evidence of a bygone era.

A half century of log drives

By the end of the Civil War, the two greatest forested regions of the United States were the Pacific Northwest and Northern New England. These two regions were the main sources for the growing nation's insatiable demand for lumber.

These forests provided the wood needed for framing lumber, pulp for paper making, and hardwoods for furniture making, cabinetmaking, and interior millwork.

Three months every spring, from the late 1860s to 1915, the Connecticut River was the main route by which millions of board feet of timber, harvested in the Northern forests throughout the winter months, would be brought to the lumber and paper mills hundreds of miles south in Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Connecticut.

The river drive brought in hundreds of loggers from around New England and Canada. Many of them had worked through the winter logging in the Northern forests, then signed on as drivers to work the river run in the spring.

The drive itself was a spectacle in all the river communities it passed through.

As described by the Brattleboro Daily Reformer in 1914, "Thousands of logs, logs big and logs little, logs pushing, jamming, drifting, plunging - covering a whole stream as with a great floor - this is the season's lumber drive on its way down the Connecticut."

The writer clarified that metaphor: "It is a floor of pitfalls, uneven and treacherous, now yielding and now gripping as in a vice the men who walk upon it. Yet there they go, those lumber-jacks, jumping from one log to another, harpooning them with their long pronged sticks, called ‘[peaveys]’ or ‘[cant-dogs],’ breaking up jams, driving the big fellows in the way that they should go - and all as nimbly and easily as you please."

People would come by the hundreds to watch the drivers and logs pass through their towns, and schools would be closed so the children could see it.

"At Bellows Falls they can only stand patiently and watch the logs as they drift slowly towards the dam, so slowly that their motion is almost imperceptible - and as they are caught in the sudden rush of the falls, plunge in a perpendicular over the dam and swirl away into the rapids beneath."

It was difficult and exciting work, and many of the drivers came back year after year. Stories of their exploits took on mythical proportions, and there is no doubt a fair amount of exaggeration in them.

But there also can be no doubt that this was also incredibly dangerous work. It was newsworthy when no lives would be lost during a given year's drive.

Lumberjacks would stand watch over the process.

"Suddenly a great log will drive over the dam and send its head into the river's bed with a thud, sway for an instant, and stop, firmly caught between two rocks," the Reformer reported. "Others come swiftly from behind. The jammed log halts their course. Logs pile upon logs. In ten minutes a monstrous structure, as of some wrecked ship, is thrown up in the river bed."

If the impact of a new log ramming the pileup was not enough to dislodge the lumber, the lumbermen would need to take more drastic measures, starting with "explosive jelly" and, for more stubborn cases and as a last resort, dynamite.

The lumber companies made the 1914 drive the largest ever, with 500 men and dozens of horses moving 65 million feet of timber down the river.

By the time the first logs reached Bellows Falls, the far end of the drive was still 80 miles upriver in Barnet, just south of St. Johnsbury.

The Bellows Falls choke point

The canal and 52-foot waterfalls at Bellows Falls created a choke point for the log drive. While a substantial number of logs would be moved down the falls to points farther south, this would have to be the final destination on the river for many of them.

In that 1865–1915 period, Bellows Falls was home to numerous lumber and paper mills along the river and below the canal, which by that time was used solely to power the mills.

The village was also a major rail center, with a large rail yard on The Island, the land between the canal and the river. Rail lines ran directly from the rail yard into some of the mills.

In North Walpole, a huge lumberyard sat along the bank of the Connecticut River below what is referred to as "Piss Pot Harbor," where a small stream enters the main river. A large brick building, still standing on the bank of the river at the end of Pine Street, served as the stable for the lumberyard horses.

That brings us around to the piers, briefly seen for just a few hours on the river bottom.

The piers are what is left of a large system used to help separate and hold the logs as they arrived on that portion of the river. The piers were used to anchor the chains and cables that created large, individual corrals in the river for the logs, depending on how they would be used.

The logs could be separated and grouped together in chain corrals, depending on their intended use as pulp for papermaking, soft and hardwoods for dimensional framing lumber, or boards for a variety of uses.

The rough and tumble drivers

The piers serve as a reminder that, as the main river drive destination, Bellows Falls and North Walpole were the villages where at times hundreds of rivermen would arrive at the end of the drive looking for an opportunity to unwind.

The taverns and brothels of the two villages were the main objects of the drivers looking to relax and have a good time after months of round-the-clock labor under hazardous conditions.

It is reported that North Walpole alone had as many as 18 licensed saloons for the end of one drive. There might also be what were termed "pleasure boats" conveniently located on the river itself.

Public drunkenness and fights were common, and one old account speaks of the rivermen enjoying live music and dancing in the Bellows Falls Square through an entire night.

Vermont writers Bill Gove and Robert E. (Bob) Pike have written extensively about the log drives, and they were around early enough to be able to interview some of the surviving drivers. They offer some sobering insight into the lives of the mythic rivermen.

End of an era

While admired for their skill and bravery, the fact that many of these loggers lived for months of the year either in the north woods or on the river meant that a good number of them never had families. Many were also illiterate.

The Reformer reported in 1914 that the lumberjacks, earning $3 to $5 per day ($91 to $152 in today's dollars), would "toil on from dawn to sunset and on through the darkness of the night, always watchful, quick and wary."

When interviewed in their later years, they were often impoverished and in nursing homes, suffering from the ravages of years of hard labor, exposure to cold, and serious injuries.

The last great river drive was in 1915, and the last log drive ever on the Connecticut was a small one in 1947.

A number of forces that contributed to the river drives being consigned to history are apparent from reading the news coverage of the era.

In 1913, a complex array of corporate changes began affecting the timber harvest and its delivery to points south. One report mentioned the possibility of "attempts to regulate the log drive." Another report called proposed federal tariff legislation that would affect the pulp and paper industry as "disastrous."

And the annual log drive was disruptive in the extreme to anyone who would normally use the river, including local manufacturers, who were expected to shut down their operations.

In 1915, the Reformer, quoting the Boston Transcript, published an account of one tense negotiation.

"Once, they say in Bellows Falls, a mill owner showed fight and announced that he would keep his plant running till an important order of paper was completed. 'I'll give you 12 hours to shut down,' said the boss of the drive. 'If you haven't quit by that time, I'll blow up the dam.' The mill owner stopped his wheels, but not his curses."

But in one huge change, the Reformer reported that most of the large trees had been depleted from Vermont. The big logs were being replaced by what the newspaper derisively called "the four-foot stuff."

"A lot of Green Mountains will have lost their greenness," the newspaper wrote in 1915. "Forestry in the United States is not yet practiced as a science by the big commercial companies."

Another 1915 article elaborated: "The International Paper company has been receiving its four-foot stuff from the White River. It has thousands of acres of land near this river, and much of is has been cut over. The contracts given the Connecticut Valley Lumber company for 1917, 1918 and 1919 probably mean that the paper company intends to conserve its timberlands for a period."

The anonymous writer editorialized that the hills and mountains from which the large timber had been harvested for so many decades "are pretty well denuded of lumber now and the big sticks this year do not compare in size with the lumber which has gone through here in other years."

"The timberlands have been cut into and now it will be necessary for them to grow again before they will yield their millions of feet yearly. The big corporations have learned the lesson that perpetual greed in denuding the mountains and hills of their timber is not a paying proposition and have begun to conserve their forestland."

The article concludes: "The passing of the Connecticut [River] drives indicates that conservation along the Connecticut valley and along the waters which feed this mighty stream has begun."

And thus ended the tradition of the annual log drive - until a brief glimpse of the clues left behind so many years later.

Additional reporting by Jeff Potter.

This News item by Robert F. Smith was written for The Commons.