HALIFAX — I was prescribed, and took, a 0.5 mg pill of clonazepam nightly to suppress night terrors for four years, starting in 2011. It's a low dose, but I became habituated - as one does.

I stopped cold turkey eight years ago this month and then used somatic therapy to heal my life-destroying sleep disorder.

This choice rescued my life.

Knowing that my medical conditions are isolating yet widespread in Vermont and the U.S., I wanted to pass on a few things I learned. For anyone stuck like I was, I hope there's something here that helps.

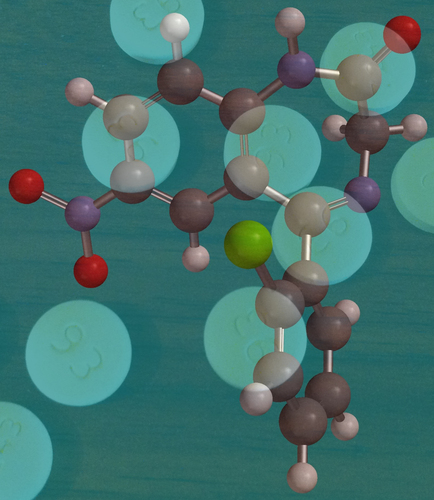

Clonazepam is a sedative in the same class (benzodiazepines) as Valium ("Mother's Little Helper") and Xanax. I depended on a prescription controlled substance to get through life for four years, and I'm far from alone. While benzos are far weaker and less fatal than fentanyl, addiction in this class has taken a huge toll over decades, and it continues to.

I offer these details so that anyone in recovery has a concrete sense of my path - what it is and what it isn't. Also, I'm benzodiazepine-free and alcohol-seldom, not substance-free. I don't want to come across as something I'm not.

* * *

As a rookie legislator this year, I was shocked at times to learn how much Vermont has normalized permanent opioid addiction. For example, Vermont's inmates have the medical right to a daily dose of a "clean" version of the more dangerous street drugs, but have no similar right to 12-step programs, and often lack access.

This is how we try to keep opioid users alive and away from illegal activity. We enforce compliance by watching their pee. The hope is that someone pisses clean for a few weeks, months, and then years, all while putting their life back together.

Maybe one day they'll choose to wean off. Until then, the opioid user gets buprenorphine. This pathway, part of Vermont's overall focus on "harm reduction," is essential to saving lives today.

In the long run for me, sobriety meant choosing to confront hard feelings and hard thoughts rather than push them away.

As I've developed that skill, it's like what author and activist Ann Braden said at a recent event in her honor: "Once you've found out what you're capable of, you don't often forget it."

* * *

What is a sleep or night terror?

It's a type of sleep disorder. It's as bad as your baddest nightmare, but also worse. Normally, while dreaming, your body is as limp as a rag doll. A sleep terror is embodied and experienced. One's body leaps into action as if in response to a real threat. There's no sense that it's a dream.

To add to the confusion, there's often no conscious recall.

My episodes started around age 7, lasting from a few seconds to a couple of minutes long. My dad became expert at running down the hall and turning on the light, which would jolt me back to conscious reality.

In one night terror, I'd hallucinated that I was being crushed under concrete. The bedroom light woke me crouching with my arms above me, pushing on the underside of the upper bunk for dear life. I'd be out of breath, feeling my heart racing but not knowing why.

I'd wake up, too few hours later, for the school bus, then stumble to the breakfast table asking, "Did I do anything last night?" Pouring cereal, I'd recall a flash of the event and the horror.

Rolling out of control in a vehicle downhill was a theme that started when I'd sleep in my Subaru while driving cross-country to Idaho at 18. I'd wake up to find myself pumping my legs for the brake but only finding air.

There's no off-switch on this disorder for sleepovers or top bunks. At home, I'd run through my (ground floor) window in my effort to escape annihilation.

At times I was able to chuckle about it, like the time I was seen running in my seat while sleeping on an airplane.

Inside I felt like a freak. My pediatrician said I'd "grow out of it," without offering any tools. Instead, I lived that car crash and other bone-crushing scenarios at least 24,090 times by the time I filled that 0.5 mg prescription in my late 30s.

Weeks after the Subaru car crash became a recurring theme, I survived a fall of 200 feet in Idaho's Sawtooth Wilderness. I labored to understand how I kept ending up injured, in seemingly preventable ways, in both waking and sleeping life.

I worried that the term "self-destructive" could apply to me and felt powerless to do anything about it.

Seeking help after that accident, I was prescribed 4 mg of clonazepam daily for what that doctor called nighttime panic attacks. I slept OK, but after five medicated months, I gained the sense that waking life had hazed over.

I quit and ended up feeling better. I started at Marlboro College months later, sober and optimistic.

* * *

Unfortunately, I never outgrew it. When my doctor offered me low-dose clonazepam in my late 30s, I filled the prescription.

Anything for relief. I was terrified to go to sleep.

In those days, the car crashes had been replaced with another harrowing scenario: watching my baby boy get smothered by a plastic bag while I clawed at the dark chasm he had fallen into.

I had trouble scheduling an appointment the first time I needed a refill. I left messages for the doctor about my fear of going off the drug. It was clear that the meds had become a crutch, but at least one that sheltered me.

When I was off medication, a quiet week was rare. I'd study myself for clues, always tweaking my diet or supplements. Nothing improved in the long run - until I addressed my underlying emotional landscape.

Adverse childhood experiences - ultimately diagnosed as childhood PTSD - left me afraid that I could die at any moment. I lacked resources to heal this and turned it into thousands of other fearful experiences.

I never stopped looking for help. Upon seeing a new doctor or homeopath or hypnotist, the conversation would come around to something like this: "Do you recall any major events when you were 7 that could have caused this?"

No one told me how identifying a formative event would heal it, and this waylaid me.

I'd freeze. I'd tell them I had a pretty normal childhood. The terror I felt around my parents, who seemed nice enough as far back as I could consciously recall, was as invisible as the air I often clutched at.

One of the diagnostic criteria for sleep-terror disorder is that the "episodes" cause significant distress in the daytime, so that was always on the doctor's questionnaire. My life had struggles, but also successes.

"I'm doing OK," I'd say, in incensed denial.

Some treatments seemed to help - for a while - and then I'd do something like jump headfirst over the footboard to escape a locomotive. Walking into my new job with a black eye, I couldn't be present with my own hopelessness. That left me disembodied.

I feel very lucky to have noticed that I was missing, often with the help of a true friend. I feel lucky that I held on to my intention to not turn a temporary solution into a permanent problem, and confuse suppression with treatment.

"Benzodiazepine medications used at bedtime will often reduce night terrors; however, medication is not usually recommended to treat this disorder," says Johns Hopkins Medicine, for example.

In 2015, I decided to leave the meds behind and try again to confront the experiences, to try to learn from them.

The first thing I faced was fear. I anticipated a "rebound reaction" of nighttime activity. I barely slept for four days.

* * *

The resource I found that fall that made the difference was trauma-informed therapy.

I still remained stuck, having identified no foundational event to heal.

This time, I got curious: "What if my body is trying to tell me something?" I wondered. I developed more tools to be present with the terrors. I listened to my own thoughts, rather than push them away.

I started seeing Lisa Newell of Brattleboro weekly for somatic experiencing, a modality in which I gave my body the respect of feeling it, with the benefit of tools that instilled safety.

Some sessions were nothing but a series of intuitive movements. One week at a time, I'd revisit my nightmare scenarios - but this time, with a coach in my corner.

I'd done years of talk therapy, but this felt different. I learned that I could metabolize hard emotions from the past and let them go.

I also continued in concert with my talk therapist, using that time to unlock my voice. Throughout 2016 (a good year for feeling triggered!) I revisited memory fragments that had long puzzled me, and I noticed ways to stop cycling through patterns.

I dare say, I grew.

* * *

The fallback explanation for my sleep disorder was "You've got bad genes."

That's how I felt - defective.

When my sleep habits and sleep loss contributed to breakups, I'd freak out about feeling abandoned. I'd search again for cures, like the time my doctor had me give every prescribable sleeping pill a five-night trial, or the time I persuaded my skeptical doctor to let me try taking an anti-seizure med at bedtime.

All of this succeeded only at getting my hopes up, and, a couple of years later, red-flagging my life-insurance application.

Medicating was a relief from the powerlessness. But to let go of it risked nothing but deeper hopelessness.

* * *

No medicine works for free. I had to show up.

Leaving the prescription and facing the music was overwhelming at first. My mental dials spun out of control.

But I survived, and felt better.

The constant tightness I felt in my chest, the congestion in my forehead for which I'd been prescribed an inhaler as a child, evaporated.

The tightness came back. But then it disappeared, for longer and longer periods.

* * *

Today, I still - often - wake with a start. But my most harrowing experiences are now only memories.

When I feel fear or anxiety, I'm more often grateful that my body's barometers are telling me something.

"There are many pathways to recovery" is something you hear about substance use. It also fits night terrors. Tens of thousands of Vermonters suffer with this disorder, and everyone finds a different path.

Some experts argue that we should reclassify sleep terrors as trauma-associated sleep disorder (TSD). Interesting idea. What if we took a fresh look at how we get kids trauma-informed therapy?

Unreported child abuse and neglect is endemic. What if, instead of expecting that a kid in an exam room will report that, the doctor just prescribed treatment on the spot?

We might be able to give more kids back their childhoods.

Tristan Roberts is serving his first term in the Vermont House of Representatives for Windham-6. Comments or questions? In honor of National Recovery Month, he's extending an invitation to reach him at [email protected] for more resources for anyone who's struggling.

This Voices Essay was submitted to The Commons.