PUTNEY — Landmark College celebrates the 30th anniversary of its founding during the weekend of Sept. 25-27.

That same weekend is the alumni reunion for Windham College, whose campus Landmark now occupies.

Landmark was born as the Landmark School in Beverly, Mass., as a high school for children with learning disabilities.

Windham College, whose enrollment hit its peak in the 1970s, was founded by Walter Hendricks, a name familiar to many locals. Hendricks started two other area schools: Mark Hopkins College in Brattleboro, and Marlboro College.

Hendricks founded his first school in Europe - for GIs - when he himself was in the armed services. After the war, he came to southeastern Vermont and started creating the colleges.

In 1951, five years after founding Marlboro College, Hendricks opened the Vermont Institute for Special Studies in Putney. The school's mission was to help international students improve their English skills enough to transfer to other U.S. colleges.

Three years later, its curriculum changed to liberal arts studies, and the school was renamed Windham College.

Barb Taylor and Karen Gustafson, members of the Windham College Alumni Association, were roommates 50 years ago at the school, and both graduated in the last few years of the 1960s.

The college “started in the basement of his house,” Taylor said.

That house was completely re-purposed for the school and became Currier Hall. It held some classrooms, offices, the cafeteria, and some music rooms.

The building, located on Old Depot Road, was recently renovated for residential use by the Windham-Windsor Housing Trust, Taylor noted.

“The purple house on Kimball Hill was Grey House, a boys' dorm. Classes were also held there,” Gustafson said.

As the college outgrew downtown Putney, Hendricks looked north.

In 1961, Windham College added two dorms on the hill where Landmark College sits today: Aiken, for young women, and Frost, for young men.

Although the expansion was necessary, Gustafson and Taylor remembered the challenge of having their living quarters so far from the rest of the college's campus.

“We had no cars,” Gustafson said.

“And no sidewalks,” Taylor added.

Still, the duo had fond memories of their college years.

“We had some wonderful people teaching at Windham,” Gustafson said. She and Taylor listed some notable instructors: painter David Rohn, art instructor Peter Forakis, author John Irving, state geologist Charles Ratte, writing teacher Don Harrington, author and academic dean Charles Fish, psychology professor Jeremy Birch, music instructor and Yellow Barn founder David Wells, and librarian Bob Rhodes, who was later hired by Landmark College for the same position.

Taylor said she could not recall faculty members who transitioned from Windham to Landmark. She noted the challenge a professor might have with going from a traditional liberal arts learning environment to one requiring the specialized teaching skills to instruct students with learning disabilities.

A few Windham alumni found the transition easier and became faculty at Landmark College.

Susan Frishberg, assistant Spanish professor and leader in the Study Abroad Costa Rica program, studied English literature at Windham College.

John Bagge graduated from Windham College, and, as town manager of Putney, was integral in helping Landmark get its footing in the town. He became a founding faculty member in the English department at Landmark, where he also coached baseball, basketball, and served as resident dean before retiring a year and a half ago.

“[Bagge] was highly esteemed by students and very much loved,” said Landmark College Research Services Librarian Mary Jane MacGuire.

David Rohn, art teacher at Windham College from 1964 to 1976 recalled, in an email to The Commons, the influence of the school's second president, Eugene C. Winslow, who died in January.

Winslow “was a very significant figure in the turbulent decade 1964-75 when he took over the presidency of the college from Walter Hendricks,” Rohn wrote.

“He was a bold, driven, demanding [U.S. Navy] captain, the first college president in the country to declare publicly against the Vietnam War.”

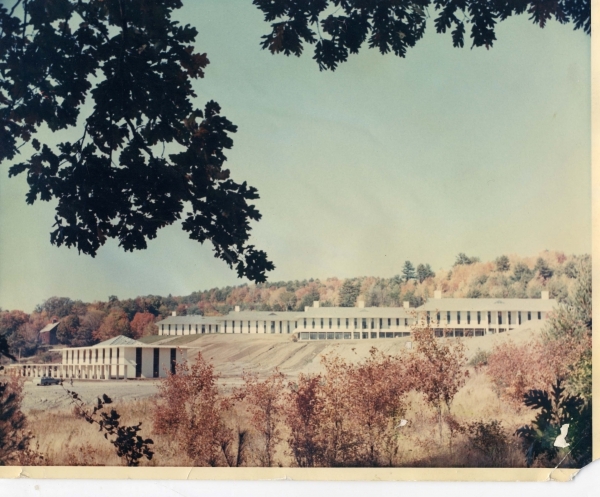

Other Windham College notables are Nobel Prize-winning author Pearl S. Buck, a trustee, and John Irving, who taught English at the college in the years when he wrote his first novel. In a later novel set in Putney, Irving described Windham College, designed by prominent 20th-century modern architect Edward Durell Stone, as “an architectural eyesore on an otherwise beautiful piece of land.”

Boom to bust

The college thrived in the 1960s and early 1970s, thanks in large part to young men hoping to avoid the draft with educational deferments.

Taylor said that in 1965, the school enrolled approximately 500 students, and in the first two years of the 1970s, it peaked at around 900 students.

In response to growth's demand, in 1967 the college secured $5.4 million for expansion of the new campus on River Road. Of that, $4.3 million came from federal funding through the Higher Education Act of 1963; the remainder was obtained through fundraising and loans. That year, the college's construction was three-quarters complete.

But, a few years later, on Dec. 16, 1978, Windham College closed abruptly, due to declining enrollment.

Taylor explained the likely cause was the end of the Vietnam war.

“They stopped drafting,” she said, so there was less pressure on men to avoid military service by matriculating.

The financial consequences of teaching 200 students on a main campus built for 1,000 were devastating.

Windham College was hardly the only victim of this cultural shift. According to an article in the Jan. 15, 1979 issue of Time, “Private Colleges Cry 'Help!,'” “Ten colleges shut their doors in 1978, bringing the total of closings for the decade to 129, more than double the number of new colleges that have opened.”

When the school closed, the remaining students - many of whom had been recruited from the Middle East, and had never experienced a Vermont winter - were escorted off campus so the sheriff's department could vacate and lock up the buildings.

“Marlboro College accommodated any of the students who wanted to get their remaining credits to graduate,” Taylor said.

Taylor worked in the administrative offices at Windham College for eight years after she graduated and said she left shortly before it closed.

“It was pretty traumatic,” she said, noting that when she was comptroller, “sometimes I couldn't find the money to pay the [college's] bills.”

Taylor said the college was “heavily mortgaged” to the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development and local banks, and the school's contents were auctioned off shortly after it closed.

With the ownership of most of the campus reverting to the federal government - the Fine Arts Center reverted to a group of local investors - the campus lay vacant, the buildings deteriorating for the better part of a decade. In the interim, it almost became a 500-bed minimum-security prison, but Putney residents voted down that plan by a 3-to-1 margin in early 1983.

Plans to turn the campus into a conference center also fell through.

Gov. Peter Shumlin, then on Putney's Selectboard, helped convince officials at the Landmark School to create a similarly focused college on the dormant Windham College campus.

Thus, Landmark College was founded in 1985.

Finding Windham alumni

Taylor said she never regretted attending Windham College as a student.

“I couldn't have gotten a better education,” she said.

Since then, Taylor said, the Windham College Alumni Association holds reunions “every five years or so.”

Locating alumni has posed a bit of a challenge, Taylor and Gustafson said.

“We don't have records,” Taylor said, noting at one time there were 1,500 people on the alumni list, “but people move or die.”

The state of Vermont has records of all Windham College attendees, Taylor said, but most of the data comes from enrollment forms, so those addresses are usually the parents of former students.

Considering that the college closed in 1978, it is unlikely those parents still live at the same location - if they are still even living. Plus, Taylor said the state charges $3 per name.

Both women invite “anybody who has fond memories of Windham to come” to the alumni events, whether they graduated or even matriculated at the college.

“Landmark invited us [Windham College alumni] to participate in their celebration” to officially open and dedicate the MacFarland Science, Technology and Innovation Center, Taylor said. MacGuire said during the weekend festivities, the college will have an “archives tent,” divided in half between Windham and Landmark College archives.

So the alumni association decided to hold their reunion the same weekend.

The ceremony perhaps surrounded by the most drama is the permanent placing of the old stone Windham College sign in Landmark's Alumni Hall garden, taking place at 11:30 a.m., on Saturday, Sept. 26.

The sign, “a big piece of granite,” said Taylor, used to sit on the corner of Route 5 and River Road, where Landmark College's sign is now situated.

After Windham College closed in 1978, shortly before the property and its contents were auctioned off to satisfy the school's debts, the sign disappeared.

“Every time we would get together for the reunion, we'd all say, 'Okay, who has the sign?'” Gustafson said.

Nobody has ever confessed. Taylor and Gustafson joked that the sign was somebody's furniture for almost 15 years.

“It would make a great coffee table, right?” Gustafson noted.

Then, in the early 1990s, “someone at Putney Town Hall came to work, and the sign was on the lawn,” Taylor said, adding, “the maintenance guys chained it to the radiator” inside the building.

There it sat for about a decade.

“For many years, we hemmed and hawed,” Taylor said. “Who does the sign belong to?”

Since there was no more Windham College, did it belong to the town?

She reached out to Peter Eden, then Landmark College's president, to ask if there was a place for it on campus.

“Peter Eden said he really wanted the sign,” Taylor said.

Eden got the sign. It currently sits in a shaded section of Alumni Garden, and on Saturday, Sept. 26, the sign will be honored by Landmark College officials and Windham College alumni.

The frame supporting the Windham College sign was constructed by Landmark's facilities crew, MacGuire said. “It shows up in a nice way,” she said, noting the structure is far superior to simply having the sign rest on the ground.

“They have been very good to us,” Taylor said of Landmark, noting the college's officials “really include us” in their celebrations.

“We want them to feel comfortable here,” MacGuire said of the Windham College alumni.

“There's a very strong bond between us and Landmark,” Gustafson said.