VERNON — The Nov. 2 news of yet another pending nuclear plant closure means that, within the next several years, Entergy will be juggling three complicated, expensive decommissioning projects in New England and New York.

Company administrators and federal officials say the coming shutdowns of FitzPatrick Nuclear in New York and Pilgrim Nuclear in Massachusetts won't delay or otherwise negatively affect decommissioning work at Vermont Yankee, as each plant has separate and substantial decommissioning trust funds.

In fact, federal records show that the trust funds at FitzPatrick and Pilgrim are considerably larger than Vermont Yankee's.

But those assurances haven't prevented some in Vermont from wondering about Entergy's nuclear commitments and the adequacy of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission's oversight of decommissioning spending.

“I worry that Entergy and the NRC are operating under assumptions that perhaps make the decommissioning trust numbers work in favor of a desirable answer. I hope I'm wrong,” said Chris Campany, Windham Regional Commission's executive director.

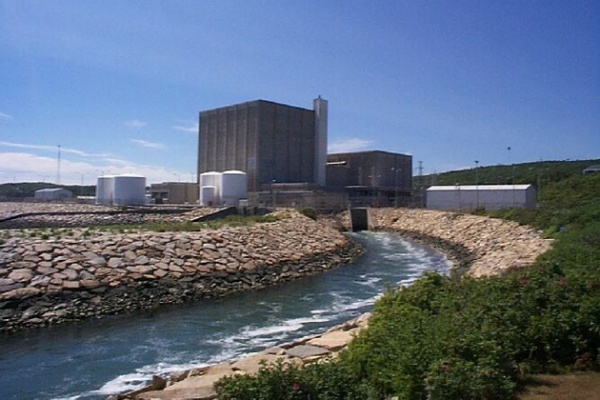

In 2013, Entergy announced plans to shut Vermont Yankee, and the Vernon plant ceased producing power at the end of 2014. Over the last several weeks, Entergy has followed with two more regional closure announcements: Pilgrim, located in Plymouth, Mass., will shut down by 2019; FitzPatrick, in Scriba, N.Y., is going offline in late 2016 or early 2017.

Common to each closure were Entergy's concerns about high operational costs and the inability to effectively compete with low natural-gas prices. There also were governmental issues: In Vermont, the company had engaged in a years-long regulatory battle with state officials who pushed for Yankee's closure; in Massachusetts, Entergy administrators complained that Pilgrim's “economic performance is also undermined by unfavorable state energy proposals that subsidize renewable energy resources at the expense of Pilgrim and other plants.”

Taken together, the three plants represent more than 2,100 megawatts of power output; more than 1,500 employees; and 125 combined years of operation. But there is another important number: The facilities' combined decommissioning trust funds surpass $2.3 billion.

The latest trust-fund reports submitted to the NRC in March show that Pilgrim ($896.42 million) and FitzPatrick ($738.34 million) have substantially more decommissioning money banked than Yankee.

The VY trust fund is listed at $664.56 million in the NRC report, but that number is inflated as Entergy has been withdrawing cash throughout 2015 and recently submitted a request for another $6.6 million withdrawal to cover October's decommissioning expenses.

Vermont officials have been battling some of Entergy's proposed uses for Yankee's decommissioning trust fund, including property tax payments and long-term spent fuel management. But the company's chief critic, state Public Service Department Commissioner Chris Recchia, said he is not concerned that Entergy's Pilgrim and FitzPatrick commitments will affect VY decommissioning.

Recchia also has pointed to funding and decommissioning assurances in a 2013 shutdown settlement agreement between Vermont and Entergy. “One thing that I'm sure about is that the agreement that we reached with Entergy will be honored regardless of what's happening [elsewhere],” he said in a recent interview.

The NRC is offering its own assurances.

In late September, Bill Dean, director of the agency's Office of Nuclear Reactor Regulation, issued a brief report saying that the latest reports from around the country show that “101 of the 104 operating power reactors have demonstrated decommissioning funding assurance.”

The owner of three Illinois reactors self-reported trust-fund shortfalls and is expected to correct those “in a timely manner,” Dean wrote.

Furthermore, NRC spokesman Neil Sheehan pointed out that there is no commingling of Vermont Yankee's trust fund with trust funds at other plants or with other Entergy holdings.

“Each plant has its own decommissioning trust fund, and that money is walled off from use at any other facility,” Sheehan said. “What's more, permanently shut-down plants must submit updates on the status of the decommissioning funds to the NRC each year.”

But there's a wrinkle in the NRC's evaluation system for decommissioning funding: The agency doesn't take into account all of the money a plant owner will need to clean up a site. A recent NRC report authored by Dean notes that the NRC defines decommissioning as safely taking a plant out of service and reducing residual radioactivity to allow for NRC license termination and some form of site reuse.

“The costs of spent fuel management, site restoration and other costs not related to decommissioning are not included in the financial assurance for decommissioning for nuclear reactors,” Dean wrote.

The discrepancy between the NRC's “minimum financial assurance” standard and the actual costs of decommissioning is clear at Vermont Yankee: The agency's minimum financial assurance for VY is $817.22 million, while Entergy has said it will cost more than $1.2 billion to decommission the site.

From Windham Regional's Brattleboro office, Campany has expressed concerns about the adequacy of Entergy's decommissioning and spent-fuel plans for Vermont Yankee. He pointed out that the U.S. Government Accountability Office in 2012 (www.gao.gov/products/GAO-12-258) found that “the NRC's formula may not reliably estimate adequate decommissioning costs.”

“Given the number of plants that have closed recently and likely will be closing, it would seem that now would be a good time for the (Government Accountability Office) to revisit their study and the basis for the NRC's determination of decommissioning trust fund adequacy,” Campany wrote in an email response to questions from VTDigger and The Commons.

“The GAO might also look at the Post Shutdown Decommissioning Activity Reports filed by the closing plants,” Campany added. “Do they provide an adequate and accurate picture of the decommissioning and associated costs?”

In response, Sheehan reached back to the NRC's rebuttal to that 2012 GAO report: The agency said its decommissioning funding formula is just one facet of a trust-fund regulatory system that includes “annual adjustments and accounting for site-specific costs.”

“Licensees must perform several steps which, when considered as a whole, provide reasonable assurance that funds will be available when needed,” the agency's statement said. “Based on experience, the regulatory system has been adequate to ensure that power reactor licensees obtain funds when needed for decommissioning.”

Sheehan also noted that the commission is working to revamp its nuclear-decommissioning rules, which have come under heavy criticism after Vermont Yankee's shutdown.

“The NRC has begun the process of developing new regulations in the area of decommissioning,” Sheehan said. “However, those new rules are not expected to be finished for several years.”

NRC regulations aside, Recchia had one other takeaway from Entergy's recent decisions to shutter three nuclear plants in the region.

“The closure announcements are interesting taken collectively,” Recchia said. “If nuclear is not economically competitive in New England, where electricity prices are high and where gas is constrained, where can it be profitable?”

When announcing FitzPatrick's pending shutdown, Entergy administrators said they remain “committed overall to nuclear power” because it is “carbon-free, reliable power that is cost-effective over the long term.”

In addition to Pilgrim and FitzPatrick, Entergy operates six other nuclear plants: Indian Point in Buchanan, N.Y.; Palisades in Covert, Mich.; Arkansas Nuclear One in Russellville, Ark.; Grand Gulf in Port Gibson, Miss.; River Bend in St. Francisville, La.; and Waterford 3 in Taft, La.