BRATTLEBORO — Most people visit art museums to look at art. Other than the occasional performance art piece or “live painting” event, very few people get to create art in a museum, especially those not self-identified as artists.

Last month, about 25 people gathered at tables in groups of four to six to create art at the Brattleboro Museum and Art Center (BMAC), but under the guise of playing surrealist games.

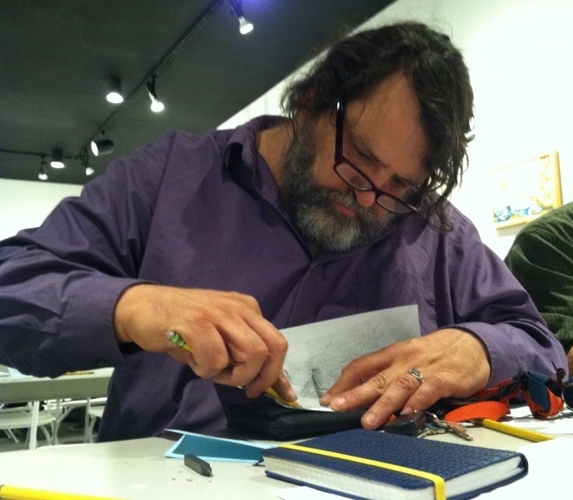

Roger Clark Miller hosted the event, acting as instructor, master of ceremonies, and DJ. His self-described “extra hand,” Debra McLaughlin, was there to make sure the technology was running smoothly while Miller went from table to table, teaching the games.

Miller has made this event a fairly regular part of his repertoire, hosting surrealist games at 3S Artspace in Portsmouth, N.H., Real Art Ways in Hartford, Conn., and at Boston's Institute of Contemporary Art.

The games Miller brought to the BMAC event were adapted from those developed by surrealist and Dada artists André Breton, Yves Tanguy, Marcel Duchamp, and others in the 1920s and 1930s.

In these games, sentences and drawings are created collaboratively by participants who don't know what the other players have contributed.

Exquisite Corpse, anyone?

Perhaps the most famous game of the series is Exquisite Corpse. Its name came from a sentence the artists wrote during an early version of one of the word games: “The exquisite corpse shall drink the new wine.”

Exquisite Corpse is a drawing game where each player draws different body parts of a person or creature before folding the paper and passing it on. It was the first game Miller taught attendees that evening.

Later on, Miller brought out an art box filled with pieces of graphite, which he invited players to use for the “automatic drawing” game, Frottage. The technique was developed by one of his favorite artists, Max Ernst.

According to Miller's website, “Frottage means 'rubbing' - in typical surrealist fashion, it also has sexual innuendos. One rubs surfaces, and creates from there.” At the BMAC event, finding surfaces not part of the art exhibit was challenging, but players managed to come up with a variety of images.

Most of the games played that night were word games, where each player gets a piece of paper and writes words or sentences according to some rule - parts of speech, a question or answer, a certain type of statement - and then folds it to hide all or part of what was already written before passing the paper to the next player.

That player performs the same task, and the paper gets passed around until some predetermined end is reached. Then, everyone reads the results and hilarity ensues.

The games are quite different from common card and board games, are noncompetitive, and require “simultaneous spontaneity,” Miller said. In hosting the games, he said sometimes players are wary of the new experience, but “partly, my enthusiasm convinces people” to play.

“The thing that makes these games interesting is how people interact,” Miller said. “It's all about the collective activity of the people at the table. You get really comfortable with people. The games let your unconscious come out in a completely safe environment. When people show up, it's a casually social thing, and the ice is quickly broken.”

Chatting like family

Miller told the story of a past event where he stopped at a table to check in on the players and saw them chatting so comfortably he figured they must be family.

Not quite. That night was the first time any of them had met.

These games are meant for everyone to play, Miller said, and demand no artistic experience. In fact, the opposite may be true.

“If you're out to prove you're a good artist, you're missing out,” he said. These games are about “letting your unconsciousness spill out.”

“Sometimes you get really interesting answers,” and even though a player doesn't know the question, “you get the perfect answer,” Miller said. “Like Bob Dylan lyrics, half make no sense, but you get it emotionally. It's really a collective experience. Everybody at the table is like a band. You get together and start jamming.”

To enhance the experience, Miller provides the event's soundtrack. Some of the music played that night included selections by Brian Eno - “his lyrics are kind of surreal, like the games,” Miller said - John Cage, Roxy Music, Juan García Esquivel, and Harry Partch, among others.

Miller also admitted that some of the music he plays at Surrealist Games is his own.

Some readers may recognize Miller from his decades-long career as a respected and versatile songwriter, composer, multi-instrumentalist, and vocalist. In 1979, he co-founded the influential Boston avant-punk band, Mission of Burma; he is a member of the silent-film-accompanying group The Alloy Orchestra; and he helped start Birdsongs of the Mesozoic, which The New York Times called “the world's hardest rocking chamber music quartet.“

Among other projects, Miller is currently working on compositions for documentary soundtracks.

So, how does someone get from releasing “Peking Spring,” one of Mission of Burma's earliest recordings, full of heavy bass and jagged guitars, to hosting Dada-inspired games in a fine art museum?

'Psychedelia made manifest is surrealism'

“I was doing surrealist games in 1975, four years before Mission of Burma,” Miller said. A teacher back home in Michigan told him, “I think you'd like surrealist stuff,” Miller said. “I was interested in psychedelia, in walking around in a dream state. Psychedelia made manifest is surrealism.”

Miller noted the B-side of Mission of Burma's first release is a song he penned called “Max Ernst,” about the Dada artist. Some of the lyrics could have come from a surrealist word game: “In the burning sea / In the laughing lights / In the luminous sea / In the brash gold night."

About five years ago, Miller met McLaughlin, who was then running the Center for Arts at the Armory in Somerville, Massachusetts. Not only did a romance between the two develop, but she offered him a place to host the surrealist games.

Although Miller still performs and records with a variety of projects, hosting the surrealist games is a way for him to share his interests, spur creativity in others, and bring in some money. “It's a way of surviving - it's a gig,” he said.

It's also a sort of debut for Miller, who moved to Guilford late last year.

“I contacted Danny [Lichtenfeld]. I kind of pestered him,” Miller said.

It worked.

Lichtenfeld, director of BMAC, and participant in the games, said the week after the event, “many people got in touch afterwards to say how much fun it was."

Attendee Vaune Trachtman said she looks forward to Miller and the surrealist games returning to the museum.

Her favorite part of the night? “That it's noncompetitive fun. Everyone's a winner!”

Outbursts of laughter

Participant Rolf Parker-Houghton admitted the event was “kind of like at my house,” explaining, “I've played games like this with my cousins.” Still, Parker-Houghton described the games as “awesome."

When asked for the highlight of the evening, attendee Ely Coughlin said, “Laughing so hard I couldn't breathe.”

“Everyone here was totally into it,” Miller said at the end of the night, which went on longer than advertised.

Miller said a thrill for him was looking around the room at each table and noticing, “They're silent, and then there's this burst of laughter. I love that.”

McLaughlin, who from her perch was able to see the entire room, gave her review: “It was nice to hear so much laughter."

So, will the museum host Miller and the surrealist games again?

“Yeah, definitely. Roger is right here in our backyard,” Lichtenfeld said. “There are many creative people around here, and they want to participate, not just passively listen. In our 'wired' society, it's wonderful to have people come together without their devices. We're using tried-and-true materials. People seek that out as a way to balance the demands of technology in our society.”

Attendees “do stuff with their hands and look at each other,” Miller said.

“People clearly came with friends, and to meet other people - and to create together,” McLaughlin said. “It's a hallmark of this region, there's kind of a 'maker' community here, a desire to be open and learn new things,” she said.

“I love doing this,” Miller said. “As creative as I am, I love watching other people make things up. You will do stuff you didn't think you could do, even if you don't consider yourself creative.”