BRATTLEBORO — “It's hard to be brown sometimes, but it is beautiful as well,” said Ezlerh Oreste to the large crowd gathered in Pliny Park.

Oreste's voice was one of many people of color who spoke during Mourning the Loss of Black Lives: The Rally for Racial Justice on July 13.

The evening's march memorialized 138 black people killed by police in 2016.

Organizers also called for the state to establish anti-bias training at the Vermont Police Academy and to make space for citizen representation on a subcommittee to evaluate those measures.

Some speakers identified their race; others did not.

The rally was organized by Lost River Racial Justice, an organization comprised of members from Windham County, Franklin County in Massachusetts, and Cheshire County in New Hampshire. The organization is a local chapter of SURJ - Showing Up For Racial Justice.

Hundreds of people attended the 5 p.m. rally, which started and ended at Pliny Park, looping down Main Street to Plaza Park at Malfunction Junction before returning to the corner of Main and High streets.

People carried signs bearing messages such as “Our silence makes us compliant,” “White silence = violence,” and “You are either on the side of the oppressed or the side of the oppressor.”

Chanting voices echoed off the downtown buildings: “Hey hey, ho ho, police violence has got to go!,” “When people are occupied, resistance is justified,” and “Ain't no power like the power of the people because the power of the people don't stop!”

One participant turned his sign away from the crowd and toward Main Street.

“No sense preaching to the choir,” he said.

Onlookers stood in doorways and sat on steps. Compared to past activist rallies in Brattleboro, participants in the July 13 event were younger and more diverse.

Call for reform in police training

Organizers called for two additions to how the Vermont Police Academy trains cadets.

So did the Vermont Partnership for Fairness and Diversity, whose executive director, Curtiss Reed Jr., wrote a letter read at the rally.

“As you anguish over recent events in Baton Rouge, Falcon Heights and Dallas, let me be blunt: The prospect of state-sponsored violence against black and brown people by law enforcement in Vermont looms ever present.

“The single-most-important constructive action to reduce this threat in Vermont is to ensure that every sworn law enforcement officer understands negative implicit racial bias - the attitudes and stereotypes that unconsciously affect our understanding, actions, and decisions - and how to avoid acting upon those biases,” Reed wrote.

Organizers called for the state to establish an independent committee or commission to review the academy's curriculum in concert with recommendations put forward by the President's Task Force on 21st Century Policing.

Furthermore, they added, not only law enforcement but also private citizens should be represented on such a committee.

The second addition: a $20,000 budget line to cover the cost of training for the committee and to bring experts to Vermont to share best practices.

“We need a transparent process whereby Vermonters - particularly those of us of color, members of mental health advocacy groups, and the LGBTQI community - can provide input on how the Vermont Police Academy, operated by the Vermont Criminal Justice Training Council, (re)aligns its curriculum and training methods to meet the recommendations of President Obama's task force,” wrote Reed.

People wishing to show support for these measures were asked to participate in Lost River and Vermont Partnership's letter-writing campaign to Governor Peter Shumlin, Attorney General William Sorrell, and Department of Public Safety Commissioner Keith Flynn.

Below the surface

Organizers took turns reading a statement that they had written collaboratively. Vermont, unlike other parts of the country, they said, “has not experienced any murders of black folks at the hands of police this year.”

Still, all is not well.

Organizers asserted at the rally - and wrote in literature passed out to participants - that Vermont's “prison and policing systems in our state reflect the systemic racism and violence experienced across the country.”

According to information from organizers, black people in Vermont are incarcerated more than white people - approximately 10 times more often. The number of searches experienced by black drivers increased from 3.6 percent in 2011 to 5.1 percent in 2015, compared to the rate for white drivers, which remained at 1 percent during the same time.

Silence settled over the crowd as people read the names of the 138 black people who died at the hands of police in 2016.

Sarah Benton, a member of St. Michael's Episcopal Church's social justice ministry, said the recent killing of too many black men and then the mass shooting of police in Dallas spurred her to attend the rally.

Benton, a white woman, added that she needed to stop standing behind her own fear and feeling of discomfort and, instead, step up and take action. And no, she said, she didn't always know what was right, but that wasn't an excuse to stay silent.

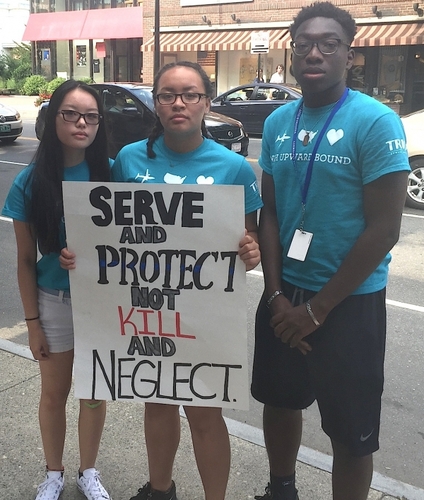

Three high-school students participating in the Northfield Mount Hermon Upward Bound program, which brings low-income students to the campus for an intensive academic program, stood by the park's pergola holding a sign: “Serve and protect, not kill and neglect.”

One student, Suraji Ahmed Omoru, who is black, said that he shouldn't be afraid of the police and should feel protected by them. Instead, he said, his mother's heart rate increases every time her son leaves the house.

She calls him “24-7” when he's out, Omoru said.

“I want to live in a safe environment, and in the United States, that's not what it is at this time,” Omoru said.

Iiyannaa Graham-Siphanoum said she chose the wording for her poster - “Serve and protect, not kill and neglect” - in part to remind some police officers that they're not performing their jobs.

Many police officers carry a lot of racial bias and need better training, she said.

The Pliny Park rally was her first rally.

“It's really powerful,” Graham-Siphanoum said later.

Police brutality is nothing new, she added - but she said that only now are people paying attention.

“Don't walk away from this rally and forget,” Graham-Siphanoum implored. “Don't wait for someone else to be killed to come together like this again.”

Mesheko Lee said that the NMH Upward Bound summer program focused on social justice. It's a topic with strong resonance for her in the wake of police brutality and the racism many people find evident in the Donald Trump presidential campaign, she said.

The younger generation still has an open mindset, Lee said.

Members of this generation are still learning, she said, and events like the rally help youth understand and build a new society.

Part of the solution?

Christophre Woods said that as a 44-year-old black man, he has witnessed police violence before - it's happened for as long as there's been black people in the United States, he said.

Police have long been used as a “weapon of racism,” added Woods, who supports re-evaluating how police are trained.

Woods told the crowd that speaking up the first time someone is victimized can prevent violence down the road.

Brattleboro Police Chief Michael Fitzgerald and a few of his officers stopped traffic for participants. He said the department was invited to the event.

The department has included anti-bias policing as part of its core training for years, Fitzgerald said.

Fitzgerald added that the department also maintains a fair and impartial policing policy, a citizens' complaint process, and use-of-force policy and trainings.

“I'm very proud of what we have done,” he said.

In an open letter to the community the chief released on July 15, Fitzgerald commended and thanked the rally organizers for creating a positive environment. The participants discussed the difficult issue of police brutality while also suggesting solutions, he wrote.

“People expect the police to respond to a wide variety of situations with thoughtfulness, compassion, respect and empathy,” Fitzgerald wrote. “I can assure you that every Brattleboro Police officer wishes to achieve that same goal.” [The text of Fitzgerald's letter appears in Voices, D1.]

A black man who said he moved to the area about a week ago said he loves that Vermont is so open.

“As colored people, you have a story - don't shut up, stand out,” he said.

Keyona Jones, a UMass graduate student who accompanied the Upward Bound student group, facilitated an open mic time for people of color. She thanked everyone for showing up. She said it was great to see so many white people in the audience.

There will always be another march or presentation to attend, she said.

Jones reminded fellow people of color to take time for self care. She said she recently took a break from social media because of the stream of racist comments in her feed.

Daryl McElveen, who said he moved to Brattleboro from New York two years ago, held a sign that read, “We're divided because we're not united.”

He's a black man, a piano teacher. He's expressive, he talks with his hands, and he offers hugs to friends and strangers alike.

McElveen said he loves Brattleboro with a capital “L.”

“I love the police here,” he said. “Vermont is beautiful.”

Ultimately, it's the creative community that's kept him in the area, he said. It took him a year to lose the idealism he held about Vermont.

“Things got a little real,” McElveen said. “A lot of black men can't stay here.”

Finding work has been hard, he continued. At first, he told himself it was because he was a stranger in a small town. But, he's watched too many people with less work experience than him hired for jobs for which he's applied.

He added, however, that he prefers not to dwell on the difficulties.

Rather, McElveen said, he wants to focus on “what connects us.”