NEWFANE — Stories, coffee, and dessert - three ingredients congenial to any fun community gathering - were in abundant supply as four speakers capped the Historical Society of Windham County's annual meeting and potluck with stories of community, the effects of Interstate 91, one-room school houses, celebrity sightings, and reunited friends.

The well-attended event took place on Aug. 19 at the NewBrook Fire Station on Route 30.

Holding a stack of index cards, speaker Larry Clark got a chuckle from the audience when he said he'd jotted down a few “random thoughts.”

Clark, a member of the Bellows Falls Historical Society, said he often ponders the question of what makes a community.

For example, he said, what's the meaning behind the question, “Are you local?”

Clark said that for his family, the answer is no. “We came up from the Cape,” he said.

In the 1790s.

Everyone belongs to a variety of communities, Clark said.

In his mind, shared stories and history define communities. Not always objective history, he said.

Objective history includes information like a town's year of incorporation, or which year the state passed a specific law, or tangible artifacts, Clark said.

According to Clark, a common refrain in Rockingham is, “We'll look it up in 'Hayes.'”

The phrase refers to the bible of Rockingham history written by Lyman Simpson Hayes and published in 1907 called, “History of the Town of Rockingham, Vermont: Including the Villages of Bellows Falls, Saxtons River, Rockingham, Cambridgeport and Bartonsville, 1753-1907, with family genealogies.”

Yet there's a lot of history the book doesn't cover, he said.

“That does not mean it didn't happen,” he said.

That “missing” history intrigues Clark. In his mind, oral tradition represents “the history of the heart,” and is not always written down.

“It's all pretty much all about the stories,” Clark said.

The oral history that community members know collectively are the bricks and mortar of community, he said. For example, a neighbor's nickname, or when locals give driving directions based on take a left at Mrs. SoAndSos or.... turn left at the old oak tree .... You know, the one that burned 20 years back.

Clark wonders about the history that didn't make it into the history books.

The historical society receives a lot of objects, like butter churns, said Clark. Preservation of such artifacts is important, he continued, but the object's connection to people and their stories are also vital.

“What's the story behind [the artifact]?” he said.

Clark grew up in a section of north Westminster known as Gageville. The Gageville School had four classrooms and eight grades.

He remembers when road work on Interstate 91 at Exit 6 stalled while contractors struggled to build a bridge over the Williams River. With a smile, Clark said, if one had an older brother that didn't mind if one borrowed his car, one could get around the state's barriers and drive back and forth between Exits 5 and 6, “like the dickens.”

A few audience members grinned, chuckled, and nodded.

Gageville is close enough to Rockingham that he could walk there, he said. Hayes does not mention Gageville.

“What has history got to do with geography?” Clark asked.

Clark muses on the difference between political boundaries and community.

That's why communities have to write their own history books, he said.

The road that covered Northern Avenue

Holiday thanked the young people in the audience for attending and the elders who brought them saying, that history is better when you have someone to pass it on to.

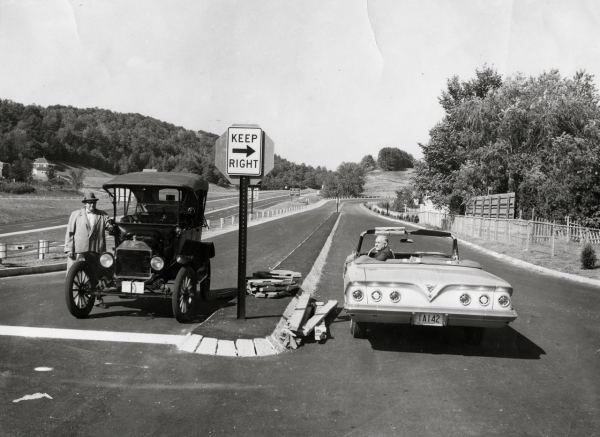

Holiday spoke about how the construction of Interstate 91 almost 60 years ago changed Brattleboro.

Prior to Interstate 91's opening, Putney Road - part of U.S. Route 5, the highway that was the main route between New Haven, Conn., and Quebec - rambled through acres of farmland, according to Holiday.

Downtown Brattleboro “buzzed” on Thursday and Friday nights, when people traditionally ventured into the grocery stores on Main Street, ran errands, and stayed to eat out.

Now, Holiday continued, Putney Road hosts most of the “mercantile” businesses, such as grocery stores and car dealerships. Downtown now has mostly “novelty” stores and closes most nights by 6:30.

Two families owned most of the farmland on Putney Road, Holiday said. As a teenager, Holiday befriended Emerson Thomas, a member of a Putney Road farm family.

According to Holiday, Emerson Thomas retired from farming and drove a truck for the Agency of Transportation.

Holiday remembers summers working on the state road crew in the summer. The Thomas family often greeted Holiday and his fellow high school classmates at quitting time. He offered them minimum wage - $1.35 an hour, said Holiday - to spend the rest of the day throwing hay bales.

Black Mountain Square shopping center, at the corner of Putney and Black Mountain roads, stands on the site of the former Thompson family home.

Holiday shared a list of sale prices people on the former Northern Avenue - formally between Brattle Street and Allerton Avenue where Exit 2 sits - received for their homes when the state and federal government seized the land. Some houses were bought and some moved, he said.

Prices on the list ranged from the mid-hundreds to $25,000.

“Dorothy Flood, my girlfriend in third grade - her house got moved to Hinsdale (N.H.),” Holiday smiled. “I lost Dorothy.”

Holiday also played a podcast the coming of Interstate 91 called “This Week in Brattleboro History” by Joe Rivers and available on the Brattleboro Historical Society's website at brattleborohistoricalsociety.org/news/2016/07/week-brattleboro-history-i91.

According to the podcast, the federal government picked up 90 percent of the cost to build the 41,000 miles of the national interstate. States paid the remaining 10 percent and agreed to take on future maintenance and repairs. The estimated average cost was $1 million per mile. In Windham County, the government seized 340 properties and approximately 2,000 acres for the interstate.

TV? Who needs TV? We have community.

Putney resident Marilyn Loomis recalled growing up in Putney and how neighborhoods stuck together, played together, and visited together.

“It's nice to see so many people out tonight because you could be home watching TV,” she said.

Loomis attended school at her neighborhood one-room, one-teacher, school house for five years. The first wedding she ever attended was for her teacher, who invited all her students.

Putney had three schools, she said.

Loomis noted that education remains a big part of Putney. Local educational institutions include the public Putney Central School, private schools Greenwood School, The Grammar School, and The Putney School, and Landmark College.

“[My friends and I] kind of entertained ourselves,” she said.

Loomis remembers a cold winter's night when, at age 6, she walked the mile and a half home from the Putney Community Center.

She's one of eight children, Loomis said. After the community Christmas party the siblings piled into the family car. Looms said she ran back into the Center to retrieve a present her brother had left behind. She returned to an empty parking space. Loomis' family had left without her.

“The worst part was when I got home, nobody had missed me,” she said.

Loomis also remembered World War II and covering her home's windows - the “blackouts” - in 1942 and 1943. She said her father sometimes took her downtown to a lookout tower where they watched for enemy planes.

“It was scary,” said Loomis. As a child, she didn't understand what was happening, she said.

As a kid, Loomis remembers going to the Community Center to play basketball and pool with other kids.

“Because none of us had TV,” she said. “We went and visited.”

“You visited more and you did more things,” she added.

Celebrities and finding old friends

Bill Toomey said the first suggestion he made as the assistant innkeeper at the Old Tavern was to change the inn's name. According to him, the Grafton Inn was what people already called the place. The trustees at the time said no. A few months before he retired they agreed. Toomey shook his head and smiled.

“I loved my job,” he said.

Toomey said he was born in Brattleboro, went to high school in Bellows Falls, and has lived the last 50 years in Grafton.

He recently retired after 35 years as the assistant innkeeper of The Grafton Inn (previously called The Old Tavern).

According to Toomey, the Grafton Inn is one of the few New England inns to have survived for more than 200 years at its original site.

Toomey said he loved to be part of that history.

According to Toomey, approximately 30 years ago, a celebrity couple booked a week in the inn. They weren't the first such couple, but their visit made a small piece of history for Toomey.

The manager for Billy Joel booked a week for the musician and then wife Christie Brinkley only after Toomey assured the man the couple would have complete anonymity. Joel's manager booked them under an assumed name, “Mr. And Mrs. Shore.”

It was early December and a quiet time for the inn, Toomey said. The couple arrived. The staff respected their privacy, he said. As their visit progressed, however, Toomey said he noticed Joel becoming more and more tense.

To help make conversation, Toomey mentioned to Joel the inn's history and its famous visitors. At Toomey's mention of a recent visit from a famous pianist, Toomey noticed Joel brighten.

But when Toomey said that it was Rudolf Serkin who had recently celebrated his 50th wedding anniversary at the inn, Joel stormed out, according to Toomey.

At breakfast a few days later, Joel signed his menu card “Billy Joel” like an autograph, Toomey continued. The waitress looked at the signature and said, “Why, thank you, Mr. Shore.”

“It was the straw that broke the camel's back,” Toomey said. The couple left the inn, rented a condo at Okemo Mountain Resort ski area, and spent the rest of their visit swarmed by people and cameras, he said.

“It's the only time in the history of the inn when we gave a guest exactly what they asked for and they were completely dissatisfied,” said Toomey.

A second unforgettable guest is a heartwarming, but sad, memory for Toomey.

Toomey said one autumn day, he received a surprise call from a hospice worker in New Hampshire named Laurie who provided care for a man in his 40s named George. According to Toomey, the woman told him, “For reasons that are completely unclear to us and completely unclear to him, he's completely obsessed with your inn.”

She said George had only months to live and asked if the inn would sponsor his visit. The inn's management agreed, Toomey said.

When George finally arrived, Toomey said the man entered the inn extremely gaunt. He had lost all his hair, remembers Toomey. As George crossed the inn's threshold he brightened, according to Toomey. Laurie took George to his room for a pre-dinner nap.

Later that evening, a couple approximately George's age arrived. As the man signed the guest ledger he noticed George's name. The man commented that his best friend growing up had the same name but that he had lost touch with him after George joined the Navy. Toomey said at that moment the elevator opened and George stepped out.

The two men looked at each other and fell into each other's arms, Toomey said. They spent the rest of their stay talking and catching up on lost time, he said.

Six weeks later George died, he said.

Toomey admitted that he's a bit of skeptic, but that moments like the timely meeting of old friends catch even his attention.

“Wow, there are forces in this world at work,” Toomey said.