Today, something odd happened. The significance of my trip to the grocery store sunk in, and the shock of it stunned me.

For the first time in my life, I used food stamps at a grocery store. And for the first time in my life, I bought food without worrying about the cost.

It took a day to understand what I'd felt: the relief, the absence of anxiety, almost an elation, as I filled my basket, then handed the clerk my electronic benefit transfer card for the state's 3SquaresVT program.

And I was shocked by the realization of the anxiety I've had my entire life around the simple, basic exercise of buying food.

The deep-down anxiety of being poor and not always knowing whether there's enough money for food has been with me so long - from childhood - that it became no more noticeable, no more significant, than the air I breathe.

But today, fully realizing that relief, and fully comprehending that lifelong anxiety, brought me to tears.

* * *

There has always been a strong aversion to “handouts” in America, a belief that if those who can't pull themselves up by their own bootstraps don't deserve any help.

Presumably, the second part of that belief is why our nation is so eager to give wealthy people and corporations a free ride, while those in dire need are left to die under bridges or in overcrowded homeless shelters.

I suppose some of that ethos has rubbed off on me because I've always had difficulty asking for help. But I've also always believed that our responsibility as humans is to care for one another. Love makes the world go 'round, and compassion makes it whole.

And why is it that I need food stamps? Why has poverty been a lifelong disruptor of my dreams and achievements?

Because I was born a female.

That's the ugly, honest truth of it, a truth that is no less true today than it was for me growing up.

* * *

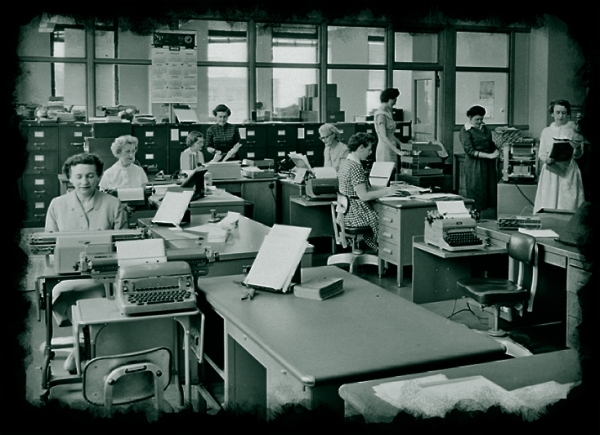

When I was a student at Joan of Arc Junior High School half a century ago, I was told I could not learn woodworking or print shop - trades that pay far better than the typing and sewing skills I was taught instead.

But my school did not allow girls to take those classes.

The school did, however, allow the band teacher to sexually molest girls. And it did allow my eighth-grade math teacher to forbid girls from speaking in his class because, as he explained, we girls were too stupid to learn math, and he was quite upset that he had to put up with having girls in his class.

By the time I reached high school, I'd been sexually assaulted quite a few times, once at knifepoint, but mostly the daily groping in the subways. By that time, I was half the person I was at the age of 7, before all the degradations took place, before the world began letting me know every day I was worth less, far less, than a boy.

By the time I reached high school, I was utterly fractured and utterly convinced that I was, as the world had informed me, not very smart and certainly not smart enough to even think about college, as if my mother could have ever afforded such a wild luxury.

* * *

And so I dropped out of high school and spent the next several decades working at jobs reserved for women: typist, telephone operator, secretary, waitress.

And because those jobs were reserved for women, they were low-paying, with little or no benefits, little or no security.

Women are, after all, the ideal disposable worker across the globe: In every nation on the planet, we are second-class citizens with little or no recourse to legal or political remedy.

We don't even have the privilege of “mankind” recognizing the endemic epidemic of gender-specific violence against us as hate crimes whose primary purpose is to terrorize and subjugate us.

But like so many women, rather than giving up on giving back to a world that gives us so little, I devoted my life to volunteer work, to the unpaid labor of helping others and of working to build a better world.

I also spent the next several decades becoming a social scientist, teaching myself the skills and academic rigor required to become a researcher and to design studies that quantify social injustice - studies like my longitudinal survey tracking levels of hate speech and bias language on prime-time television.

And yes, I taught myself math, because how else can you quantify the world around you? And because I discovered that, as a female, I am quite good at math.

* * *

Because of the professors I met who used my work in their classes, because of their urging and encouragement, I did finally face my fears and go back to school, first getting my GED at the age of 54, then my bachelor's just two years ago. I hope to return to school and eventually get the Ph.D. that was denied me the day I was born a female.

By then, it will still be too late to have built up a lifetime of good earnings, of saving some of those good wages for my retirement, of equal pay for equal work, of open doors to any job I can learn and handle, of believing myself to be capable of my full potential because the world nurtured and valued me.

I consider myself lucky that, as a female, I don't have the additional economic and emotional burden of single motherhood, stigmatized and impoverished by the honest, ugly truth of a society that despises females.

I do still have trouble asking for help from my friends. But from a society that has done more than its share to marginalize, deprive, and impoverish me solely because of my gender, I have no trouble whatsoever getting financial aid to ease the burden of poverty placed on me.

And to finally lift that anxiety that has been a constant, open wound fracturing my soul.