PUTNEY — On Dec. 2, I flew to Chicago for a national gathering of citizens concerned about the growing stockpile of nuclear waste from power generation in the United States.

The participants were all people who share an understanding that there is no good answer to this problem, that any “solution” is rife with dangers, and that creating more of this poison is immoral and imperils our future.

Three of us from the area participated in this summit. We brought our familiarity with the issues of the Vermont Yankee site and the potential plans for decommissioning.

* * *

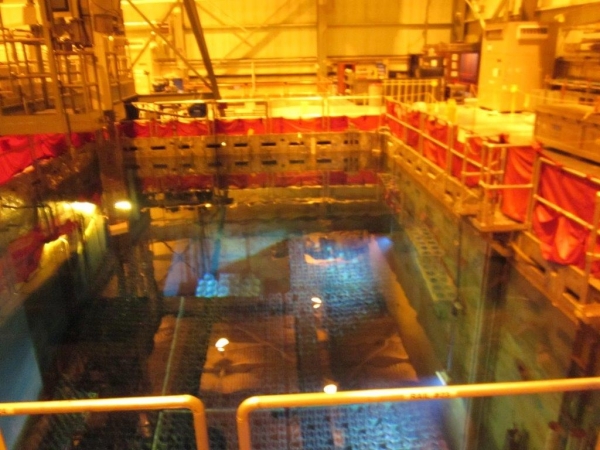

At present, the high-level waste - the most toxic for the long term - is either in casks on the site or in an overcrowded pool six stories above ground level.

As the reactor shut down, the last “spent” fuel rods entered the pool in January 2015. These highly radioactive rods need to spend some time in the pool - the “conventional wisdom” is five years - before they can be transferred to dry casks, which should be completed in the next two to four years.

The week before this conference, Entergy announced its plan to sell the reactor to NorthStar, a company formed in 2014, for decommissioning.

This company has never dismantled a reactor larger than a small university research reactor, although it has partnered with a more-experienced company, Areva. There is much we do not know about this business, but the options for radioactive waste remain the same.

This waste is toxic for at least 10,000 years, so we are talking about a need for very-long-term isolation.

The casks that Entergy has chosen and that the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) has approved are low-tech casks. They are guaranteed for only 25 years, and there is no remote monitoring: a person has to measure the radioactivity on site.

Should a cask fail - a real possibility over hundreds or thousands of years - it is unclear what could be done to fix the problem.

These casks are sitting out in the open on the bank of the Connecticut River. In this era of rising water due to climate change, would these casks maintain integrity if they were immersed? They could definitely not stand up to an attack from the air. They are not considered transportable, although they are theoretically able to be moved in secondary surrounding casks.

In Europe and Japan, this waste is stored either below ground or in a secure building, in much stronger casks with a much thicker metal shield and remote computer monitoring capabilities.

Better technology exists, but Vermont Yankee and the NRC choose not to use it.

The automatic response of most communities hosting this toxic waste: Get it out of here, yesterday! That is certainly a sensible reaction, but where would it go, and how would it get there?

* * *

Assuming NorthStar takes possession of Vermont Yankee, the company will partner with Waste Control Systems (WCS) of West Texas, a company whose radioactive waste storage operation is atop the Ogallala Aquifer, the largest in the United States, providing drinking and agricultural water for mostly arid areas in eight states.

WCS would like to become the site for a “temporary” repository for high-level waste. Vermont Yankee's casks might be the first to make their way to this rural, predominately Mexican-American, area.

The government has plans to ship the huge casks of this stuff by train - beginning with a winding, hilly track along the Deerfield River en route to Albany. The waste would then make its way to West Texas, traveling through many of the major urban areas east of the Mississippi.

Our rails and bridges, hardly in pristine condition, could potentially trigger a catastrophe. A derailment or a collision could have unprecedented and dire consequences, releasing potentially deadly radiation and requiring evacuation of a large, densely populated area.

Once these casks arrive in West Texas, the plan calls for leaving them in the open in the desert sun, with wide temperature shifts of 30 to 50 degrees between day and night.

Of course, there is no way to know how these temperature extremes will affect the waste or the casks over hundreds of years.

The new administration in Washington might try to rekindle the effort to create a long-term waste repository at the geologically unstable and strongly opposed Yucca Mountain in Nevada, or another yet-unnamed deep-ground repository.

WCS, Yucca, and other sites used for nuclear waste tend to be on Native American land, or within Black or Latino communities, such as Barnwell, South Carolina. Poor and non-white communities often become industrial “sacrifice zones.”

* * *

No solution to the nuclear-waste dilemma is without problems. However, we can make the waste less treacherous as it sits along our river.

It should be surrounded by earthen berms to protect it from potential damage from rising water or hostile actions. The casks should be regularly monitored for cracks.

We should have an emergency planning zone around the reactor for the times when the waste is transferred from the pool to the casks and should a transfer take place to move the casks to another site.

And if the waste is moved, it should not go to an “interim storage site.” It should end up in a deep geological repository that is stable and final, where the plutonium is isolated from the world of the living.

Forever.