BRATTLEBORO — Did you ever wonder what poets think about when they sit down to write their poems?

A new book from University of Pittsburgh Press addresses not only this but many other issues concerned with the art of writing poetry.

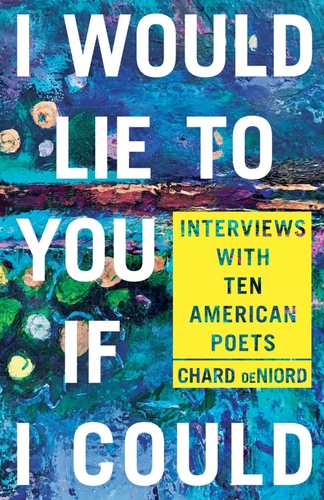

I Would Lie to You if I Could: Interviews with Ten American Poets, edited by the current poet laureate of Vermont, Chard deNiord, contains conversations with eminent contemporary American poets.

Mainly over the past five years, deNiord interviewed Natasha Trethewey, Jane Hirshfield, Martín Espada, Stephen Kuusisto, Stephen Sandy, Ed Ochester, Carolyn Forche, Peter Everwine, and Galway Kinnell, as well as James Wright's widow Anne.

Guided by deNiord's insightful questions, these poets talk about their poems and development as poets self-effacingly, honestly, and insightfully, describing just how, when, and why they have pursued writing poetry as a career.

An eminent poet himself, Chard deNiord published his first poetry collection, Asleep in the Fire (University of Alabama Press, 1990), while teaching comparative religions and philosophy at The Putney School.

His other poetry collections include Interstate (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2015); Speaking in Turn, a collaboration with Tony Sanders (Gnomon Press, 2011); The Double Truth (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2011); Night Mowing (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2005); and Sharp Golden Thorn (Marsh Hawk Press, 2003).

Currently a professor of English at Providence College, deNiord lives in Westminster West with his wife, painter Liz Hawkes deNiord, who provided the cover art for I Would Lie to You if I Could.

'Courageous new trails'

DeNiord authored an earlier book of interviews with renowned American poets titled Sad Friends, Drowned Lovers, Stapled Songs: Reflections and Conversations with Twentieth Century American Poets (Marick Press, 2012) featuring Robert Bly, Lucille Clifton, Donald Hall, Galway Kinnell, Maxine Kumin, Jack Gilbert, and Ruth Stone.

“My first book contained interviews with senior poets who were giants in the poetry world,” said deNiord. “These were writers forging courageous new trails in the wilderness after the era of the icons of modernism like Eliot, Pound, and Stevens.

“Most of these poets were then in their 80s and 90s, and I thought it important to interview them while I still had the chance. And indeed, now so many are dead, such as Hall, Kumin, Kinnell, and Bly. I sometimes still could kick myself when I recall something I might have asked them but no longer have the opportunity.”

DeNiord chose to concentrate in his second collection of interviews mostly on mid-career and a few senior poets, “a vital cross section of American poets that represents various age groups, ethnic identities, and social background,” as he writes in the introduction to his new collection.

The majority of the poets are in their late 40s and 50s.

“This book is an attempt to showcase some strong writers of American poetry today,” deNiord said. “Each author has a body of work that is worth reading, is memorable and important. The authors I have selected are very widely read and have many honors. I believe their works speak for themselves. I am not an agent promoting specific poetry.”

DeNiord feels that, like in this earlier volume, the poets interviewed in I Would Lie to You if I Could are trying to find their own voices against giants of the past, often the very poets interviewed in Sad Friends, Drowned Lovers, Stapled Songs.

“Every generation of writers must come to terms with the achievement of those who came before them,” deNiord said, “and the poets today face a problem that the earlier generation didn't have: To put it simply, we live in a world with a lot of poetry being written and published.”

A crisis in poetry?

Because of this, deNiord believes we are facing a crisis in reading poetry.

“More than ever, there is too large a marketplace, with no responsible person guiding the ship,” he says.

As deNiord writes in his introduction, “One might in fact be tempted to say that the unedited glut of poetry that appears on myriad websites had rendered poetry a drowned literary river. Any serious reader of poetry feels overwhelmed by the unmanageable abundance of poetry that has swamped the new poetry market.

“With so much writing available in the age of the internet, and thousands of new poetry magazines appearing, it is difficult for any reader of poetry to figure out what to read.”

“The great irony is that in the United States hundreds of little journals of poetry appear every year, so much so that the Library of Congress can't even keep up cataloguing them,” deNiord said.

“Yet go into any small bookstore to look for poetry and what will you find? Maybe five or six volumes, perhaps a book by Billy Collins or Mary Oliver, or some classic poets like Robert Frost or Walt Whitman. The fact is, book stores don't know what to stock. They are rightly hesitant to try to sell a poet no one knows from Joe Blow.”

DeNiord believes that a book like his collection of interviews is a way out of this morass.

“While these interviews make only a small start at representing the diverse crowd of American poets, they nonetheless provide a small but revealing window into contemporary American poetry,” he says.

Prepare, prepare, prepare

Perhaps because he considers what he does so important, deNiord takes great care in preparing for his interviews.

“I discovered early on that the best way to interview a poet is to know their work closely,” he explains. “Otherwise the poets feel that you are just guessing, and you do not care about what is most important to them - their poetry.

“If poets sense you do know and care about their work, they open up to you. Consequently, I prepare meticulously for each interview. In fact, in my interview with Galway Kinnell, he said 'I think you over-prepared' (whatever that exactly means). He then suggested we do it over again, which we did.

“A good interview should be as much like a conversation as possible. So often in the midst of an interview, I will think on the spot of something I hadn't considered in preparing, and the interview can take a different direction than I initially planned.”

To make his subjects feel fully at ease, deNiord assures the interviewed poets that they will have complete say in the final edit.

“Poets take this very seriously,” he says. “With someone like Kinnell, he took over two years before he finished work on the final draft of our interview.”

Kinnell in fact edited out much of what he said in his interview with deNiord. After reconsidering later and talking with Kinnell's widow who gave her approval, deNiord is including a longer version of that interview from Sad Friends, Drowned Lovers, Stapled Songs in I Would Lie to You if I Could.

DeNiord thinks it important to hear poets talk about themselves.

“Oddly enough people at first seem more interested in poets' lives than their poetry,” he says. “How many more people know stories about Sylvia Plath's life than can name a single one of her poems? Often only after getting to know them as people do readers turn to the poetry.

“But if truth be known, except for some flamboyant exceptions, writers do not have that interesting lives. Most of their time is spent with the rather humdrum occupation of writing.”

Larger implications

While the poets talk about many things, including their lives, the primary discussion in I Would Lie to You if I Could is about the craft of writing. But deNiord feels that subject has larger implications.

“The poets of course speak for themselves but do so in many ways that reverberate deeply in genuine and generous ways,” deNiord says.

“Poets testify to the demotic nature of poetry as a charged language that speaks uniquely in original voices, yet appeals universally,” writes deNiord. “As individuals with their own transpersonal stories, the poets have emerged onto the national stage from very local places with news that informs universally, witnessing memorably to their respective insights into what it means and feels like to be alive today as a poet and citizen in America.”

As deNiord pithily puts it, “Just as it did Chaucer, Shakespeare, or Whitman, good poetry today informs culture in a meaningful way.”