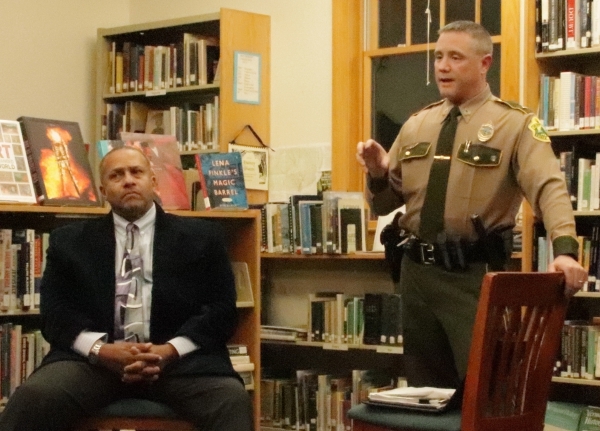

PUTNEY — Race is “one of the most uncomfortable things to talk about,” Representative-elect Nader Hashim told a group assembled at the Putney Public Library on a recent Sunday evening for a discussion on the policies the Vermont State Police has adopted as part of its Fair & Impartial Policing initiative.

However, Hashim noted, “It's good to get uncomfortable. This is where we make progress.”

Those attending the Dec. 16 discussion learned that Vermont State Police personnel have been engaging in such discomfort in long efforts to change the culture of law enforcement to adapt to an increasingly diverse state and nation.

The police have also cast a wider net in their hiring practices, and they have undertaken training and efforts to reinforce that training, according to Lieutenant Garry M. Scott, the director of Fair and Impartial Policing and Community Affairs for the Vermont State Police, and Etan Nasreddin-Longo, a visiting professor at Marlboro College who co-chairs the VSP's Fair and Impartial Policing Committee, on which Hashim also serves.

And as those efforts take hold, state statistics on bias and disparity in traffic stops are showing signs of improvement, Scott and Nasreddin-Longo said.

Over the course of the evening, the two addressed a continuous stream of concern and skepticism about the cooperation of the state police with federal agencies newly emboldened by shifts in federal policy to identify and deport undocumented people.

Hashim, the son of immigrants from Egypt and Iran, will soon go on leave from his job as a state trooper to join longtime legislator Mike Mrowicki in representing the Windham-4 district in the 2019-20 biennium in the Vermont Legislature.

In response to constituent concerns, Hashim and Mrowicki are planning monthly public conversations, with a focus on race relations.

For this first session, “We're starting with law enforcement,” Hashim said, and noted future discussions may include race relations in schools.

Many of the questions and comments from the audience had to do with the VSP's interactions with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and if such cooperation is consistent with the mission of fair and impartial policing.

By the numbers

Vermont is the only state in the nation to employ a director of fair and impartial policing, Scott said. The position was created in 2016.

Although the state's data has improved in the past few years, Vermont is far from the only state whose police force has a history of pulling over black and Hispanic drivers - and searching, ticketing, and arresting them - at a much higher rate than they do whites, relative to their percentage of the population.

Statistics quantify the experience of people of color in Vermont who have experienced the phenomenon of “driving while black,” being pulled over for reasons so minor or pretextual that leave little doubt that race or ethnicity have played a role in enforcing the law.

In 2010, the VSP commissioned two professors, Stephanie Seguino of the University of Vermont and Nancy Brooks of Cornell University, to study the issue.

In 2016 Seguino and Brooks made a presentation, “VSP Racial Disparities Analysis, 2010-15,” based on five years of research.

Although African Americans represented 1.6 percent of the state's population, they represented between 1.8 and 2.4 percent of VSP traffic stops during the study's duration.

Conversely, whites made up 95.1 percent of the population and represented 95.6 percent of the stops.

The data show black people were about twice as likely to get arrested as their white counterparts - and at least four times as likely to get searched.

When broken down by jurisdiction, the Brattleboro barracks - now closed and merged into the Westminster barracks - showed some of the highest disparity between blacks and whites in search rates: 8.4 percent of black drivers got searched during a stop, while 1.4 percent of white drivers met the same fate.

The Fair and Impartial Policing Committee started in Brattleboro in 2005. The panel conducts open meetings four times each year. Nasreddin-Longo co-chairs the committee with VSP Major Ingrid Jonas.

According to Scott, the group takes public input and turns it into policy and training.

Nasreddin-Longo told The Commons that the 2019 meeting schedule and location are still in the works, with the first meeting tentatively set for March. Once he and his VSP cohorts finalize the schedule, it will appear on the VSP's website and Facebook page.

Changing a culture from within

Since the committee's inception, the VSP has incoporated fair and impartial policing into its training of current staff and new recruits, and the police force is trying to change the culture, Scott said.

The numbers are getting better, he said, but there's still work to do.

Reading reports and analyzing data provided “lessons learned,” Scott said, but the VSP's continued efforts are not completely data-driven, he said.

It is just as important to “[hear] people's stories in marginalized communities,” he added.

“There are challenges, but we're heading in the right direction,” Scott said. Some of that direction includes reaching out to historically black colleges and universities for new recruits.

As a result, the VSP is starting to see more applications from people other than “mostly white men out of Norwich University,” he said. “Now, we ask applicants in interviews, 'How are you going to bring diversity to the Vermont State Police?' We get them to think.”

Scott gave some details on other work the VSP is doing to improve diversity in its ranks and its culture, including taking implicit bias tests, as well as working with Black Lives Matter and the state's Jewish communities.

Troopers also participate in trainings with the Burlington-based Pride Center of Vermont on issues of gender identity and sexual orientation - for example, learning how to use LGBT-inclusive language and how best to interact with a person whose gender presentation differs from the gender, name, or appearance on a driver's license.

This training has been “going really well,” Scott said.

Steffen Gillom, president of the Windham County NAACP, asked Scott to elaborate on changing the culture to make the VSP a welcoming place of employment for people of color and those from the LGBT communities.

The latter, he said, could be adversely affected by “covert bullying by straight men,” said Gillom, who noted the first recruits from those communities could feel alienated, especially if they come from an activist educational environment where “calling out” oppressive behavior is encouraged.

“I'd hate for them to come in and be squashed [for doing] what they were taught to do,” he said.

'A work in progress'

Nasreddin-Longo, who noted he recently did some training with the VSP on LGBT people in leadership roles and in the state police force's greater culture, responded.

“I talk about behaviors and the effect of those behaviors” on people, especially people who are “sometimes not out of the closet,” he said.

“This is a work in progress,” Nasreddin-Longo said, and added, “We haven't gotten to Utopia yet. We're trying.”

Hashim noted the VSP's newer, younger recruits are more progressive than some of their older counterparts, but the enthusiasm of the younger officers can “get eroded” by the “older, cynical” troopers.

The VSP has established an informal peer program as part of the fair and impartial policing program to help keep everyone on course.

Have attitudes and perceptions changed, asked one audience member, or has the VSP simply seen more “agreeable compliance”?

“It's overwhelmingly gotten a lot better,” Scott said.

“There's some frustration, and wariness about being called racist,” said Nasreddin-Longo, who added, “Beyond that, there's a lot of listening.”

Nasreddin-Longo shared a story of using photos “of the violence in Selma” of whites against African Americans to make a point during training. He told the troopers, “Nobody in this room is to blame for this. [But] we're all responsible for it.”

An audience member asked how the VSP mitigates against bias uncovered during a recruit's training. Scott admitted he's “short on data, and long on conversation and training.”

Nasreddin-Longo added that one way to mitigate unconscious bias is to tell troopers, “You have to stop yourself before the behavior and ask yourself if you'd do the same thing” if the person were non-white, non-cisgender, or a member of another minority community.

Scott acknowledged that “a room full of mostly white guys will get mad when you call them a racist” and that “it's a roller-coaster ride through this process” of uncovering implicit bias.

Federal funding withheld over state policies

One challenge the VSP faces, Scott said, is a cut in funding, including that which was supposed to help the state deal with the opiate epidemic.

Because the state's policies on when and how law enforcement can interact with federal agencies such as ICE are more restrictive than what the federal government demands, Vermont lost access to this money.

In 2017, Gov. Phil Scott signed into law Act 5, “An act relating to freedom from compulsory collection of personal information.” The state law prohibits police from gathering information about one's immigration status and sharing it with other agencies.

Act 5 also makes it clear that state police may share such information during criminal investigations at personnel's discretion.

“If we make an arrest, we can't prevent the officer from contacting the federal authorities. The officer decides,” Scott said.

He noted that in the past two years, the VSP made only one such call to federal immigration authorities.

Scott said the VSP would work with ICE “if a federal judge signs a criminal warrant,” but not a civil warrant.

During the presentation, one audience member asked if the loss of funding would hinder the VSP's efforts in continuing and improving the fair and impartial policing training program.

“If there's no funding, there's no teeth,” the audience member said.

“We're going to do it anyway,” countered Scott, who added, “we do what we can to fill the need. We want to continue with [the program] as a culture in the Vermont State Police.”

Jaime Contois, who volunteers with the American Civil Liberties Union's People Power campaign, said migrant justice groups want the VSP to keep immigration issues and fair and impartial policing connected.

Contois urged the VSP to “stay strong against” complying with ICE.

“Jeff Sessions, or whoever replaces Jeff Sessions [as U.S. attorney general], needs to know it's not okay to tell us in Vermont how to work in our communities,” she said.

Dummerston resident Marcia Daoudi asked Scott, “What happens when ICE calls you?”

“They haven't,” said Scott, who added, “they usually call the [Department of Motor Vehicles].”

On Nov. 14, the Burlington-based immigrant rights group Migrant Justice filed a lawsuit in the U.S. District Court in Burlington.

The suit alleges the Vermont Department of Motor Vehicles, ICE, and the Department of Homeland Security have engaged in illegal efforts in “surveillance, harassment, arrest, and detention” of activists, and that representatives of those agencies have infiltrated Migrant Justice's meetings through civilian informants.

The VSP wasn't named in this lawsuit.

'I'm not calling ICE'

As a state trooper, Hashim said, “If I have the option to call or not call ICE, I'm not calling ICE. I can't do that to another person.”

But, he noted, another trooper might decide otherwise.

Ann Schroeder, also with the ACLU's People Power initiative, urged the VSP to make policy explicitly prohibiting troopers from working with ICE.

“We have no cases where we've asked someone for their 'papers,'” Scott said.

When asked what was the VSP's biggest challenge with the fair and impartial policing program, Scott said, “the immigration issue.”

“Our agency wants to make sure a migrant worker [or other undocumented person] is comfortable” calling the state police or other first responders, like an ambulance, without fear of being turned over to ICE.

With the proliferation of human trafficking, where a person who possibly committed a criminal offense - prostitution - is also likely a victim of a crime, this goal is especially critical and challenging to navigate, Scott said.

Another challenge, Scott said, is “making sure our members know our mission” and that if they make it through training “with big biases and bad behavior, that it will tarnish the organization.”

“We want to serve all Vermonters,” he said.