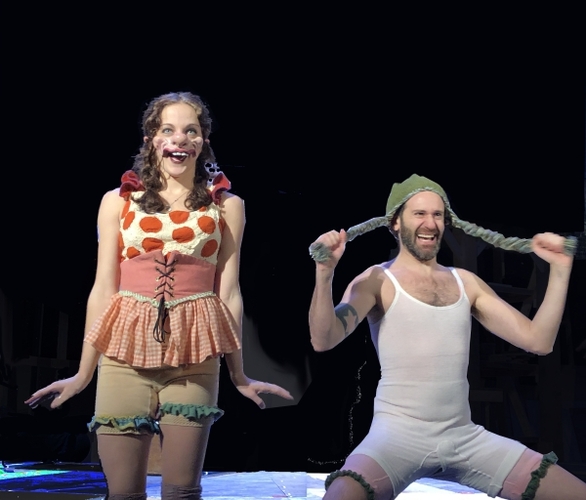

SAXTONS RIVER — Cabaret, a landmark musical when it opened in 1966, will reveal its potency once again when it opens Friday, March 13 at the Bellows Falls Opera House. This decadent entertainment depicts the rise of the Third Reich as seen through the veil of a seedy nightclub.

As the dancers cavort before us, we become distracted, laughing, titillated by the exuberant depravity. Caught up in the 1920s version of sex, drugs, and rock and roll, we laugh along with the expanding nationalism and hatred.

As the Emcee states, “We have no troubles here! Here, life is beautiful! The girls are beautiful! Even the orchestra is beautiful!”

Cabaret is perhaps the musical for this moment in U.S. history, when similar forces numb us into complacency and confusion while hate rises again.

* * *

I am a Jew whose German grandparents fled the Nazis, while many other family members stayed behind and died. I was brought up to remember the Holocaust, and a central message of this education was one of watchfulness. The moral was, “This could happen anywhere. This could happen here.”

For the first time in my life, the warning feels prophetic.

A pronounced shift toward fascism and the conditions that support it is taking place in the United States. Signs of this trend include growing nationalism, denigration of and dismantling of the free press, reduced faith in free and fair elections, development of an outcast group, an assault on the truth, mass detentions and deportations, the expansion of hate, rejection of democratic norms, an expectation for loyalty over integrity, and rampant cronyism and corruption.

There are increasing attacks on immigrants, Jews, and the LGBTQ community throughout the nation. Indeed, the Southern Poverty Law Center reports that hate groups in the U.S. are at an all-time recorded high.

* * *

I remember as a child being shown films of Hitler's rise and Kristalnacht (the Night of Broken Glass), and wondering why the Jews didn't all leave Germany when they had the chance. Recently, I asked myself what signs would push me enough to leave the United States.

Huge crowds at Trump rallies chant “Send her back,” referencing a Somali-born Minnesota congresswoman whose views they dislike, while our president smiles supportively. Media outlets like The New York Times and NPR are decried as “fake news,” while new papers like The Epoch Times appear, promising “the real truth.”

Immigrants, Jews, and LGBTQ people are targeted in mass shootings in nightclubs, synagogues, and Walmarts. Weeks ago, I watched as Jews moved to hidden locations to worship in Brooklyn following a new spate of shootings.

Not once have I considered any radical action. Certainly I have no plans to move.

* * *

I think of Germans, confronted with the growing Nazi threat, and imagine them thinking, “What can I do? I'm not going to leave my children and relatives. I have a job.... Where would I go? I belong here. It'll blow over.”

These lines seem almost directly pulled from Cabaret.

Living in Berlin, the most decadent city in the world in the late 1920s and early 1930s, perhaps it was easy to forget political events.

More than decadence, however, Germans were caught in the spell of “making their country great again.” They had lost the World War, which was then followed by a serious depression, and the nation reeled from its plummeting status on the world stage. Hitler promised a resurrection: Germany was to become great again and, by extension, so would Germans.

In Cabaret, we can watch as more and more of the German population become swept up in this nationalistic fervor. They sing: “The branch of the linden is leafy and green,/The Rhine gives its gold to the sea./But somewhere a glory awaits unseen./Tomorrow belongs to me.”

“Now Fatherland, Fatherland, show us the sign,/Your children have waited to see/The morning will come when the world is mine/Tomorrow belongs to me!”

* * *

The United States of America, too, has a population that has lost its status. Years ago, great respect was offered to the (often white) blue-collar worker who sacrificed to provide for (typically) his family.

Not only have many of these jobs disappeared, but the honor once afforded such commitment has eroded, with Homer Simpson now symbolizing this once-respected demographic. There is, as so many have reported, a great sense of loss and resultant anger in our country and a population looking to recover lost pride.

Enter nationalism, where pride in the nation supplies, by extension, pride in the self.

But, as in the vast majority of nationalism seen in practice, this is not a benign love of country. Fed with a narrative that America is under siege from a combination of racial minorities and liberal elites, current nationalistic sentiment is not inclusive. It is predominantly white nationalism and seems on the edge of boiling over into violence.

Indeed, the Southern Poverty Law Center reported in 2018 that, “From the Parkland, Florida, shooting of 17 students in February, to the massacre of 11 at a Pittsburgh synagogue in October, white nationalists or those inspired by white nationalism have committed violence at an alarming rate, killing at least 40 people in North America this year alone.”

We don't yet know the limit of what those chanting people at Trump rallies - the ones who say they want to lock people up and send them away - would tolerate in practice.

But looking at this moment as I rehearse Cabaret and reflecting on the lessons of my upbringing, I am afraid to find out.

* * *

What was the right way to respond to Hitler's rise in the 1930s? What messages could Germans have sent one another that might have diffused the situation? What institutions were allowed to collapse in a sequence of events that permitted the rise of evil? And how might these lessons help us now?

One thing feels clear to me: We must care for one another and reach out to understand one another's feelings and experiences to diminish collective anger and distrust.

We must care for the rule of law with all our strength.

We must care for a free press.

We must care for the truth.