BRATTLEBORO — Black lives matter.

These three words continue to evoke anger, hope, or indifference depending on your political persuasion. As with so many issues in these polarized times, people at the ends of the spectrum are likely to be animated regarding their significance.

I will state unequivocally that Black lives matter, but I will explain my position with cool and dispassionate reasoning.

For people who are not Black/Indigenous/people of color (BIPOC), the question becomes, “Why do Black lives matter, and what about my life?”

I have been pondering this question ever since an acquaintance said to me, “George Floyd must have done something bad for the police to treat him like that. What do you think?”

I cried out in anguish. I was horrified beyond belief - horrified with all of my being - that anyone could think that such a horrible act against humanity could have a smidgen of justification.

Regardless of the egregious acts of criminals, our civilized society is organized to give them due process and ensure their rights are not trampled on - or, at least, that is the way our society should work.

So I had to ponder: Why does the nation currently have a Black Lives Matter movement, and why would anyone think that George Floyd's killing in cold blood and in full view of the public was justifiable?

I refused to accept the blanket term of “racism” as an answer, and I allowed my pondering to take differing tracks.

Is there a narrative deep in this nation's psyche that Black people are generally takers from society and not contributors? A reason some politicians label us as “Willie Hortons” or as “welfare queens”?

* * *

Before the pandemic and our other recent troubles, the United States was seen as a desirable destination for much of the world. Per capita income is the highest in the world, and this country has exported much of her culture along with her love for democracy and right to self-determination. “American exceptionalism” has been our unofficial slogan.

However, much of what makes America an economic powerhouse today is the free, coerced labor from Africans who came to these shores generations ago, and much of what makes her unique is the exceptionally talented descendants of those former slaves.

The trouble for BIPOC folk began when Christopher Columbus marginalized the Indians in the West Indies and claimed the never-before-seen lands for Spain. Thereafter, the vilifying of people of color became the new norm whenever they were exploited for their land, labor, or bodies.

The gifts they have brought to this country are deeply embedded in our collective wealth - from the banking industry to our American culture, but contributions of African Americans have at various times been stolen, overlooked, marginalized, or taken for granted.

The struggle of BIPOC folk in general exemplifies what has and continues to make the U.S. exceptional - a feeling of a right to self-determination, an indomitable soulful spirit fed from within, and a drive to succeed in spite of great odds.

Taking from this rich tapestry without acknowledging or rewarding the source leads to impoverishment on both sides: Black people lose the wealth they should be rewarded for their talents, and the rest of society is bereft of holistic information.

On the one hand, there is resentment from BIPOC folk, because they do not feel duly rewarded for their talents; on the other hand, there is needless resentment by White folk against people of color because they lack the information on the contributions people of color have made.

* * *

Not knowing the reason Black lives truly matter to this nation is like having cataracts and not having access to eyeglasses. A bigger spotlight has to be shone on the contribution of Black lives to the American economy in terms of lost wages, lost property, and lost lives. What seems even harder to acknowledge is the continued contribution of BIPOC folk to the sciences, the economy, our collective good, and our gene pool.

It is easy to understand the contribution of Mahalia Jackson and Maya Angelou to the Arts. On the fun side, America has exported rapping and twerking to the world. It is also easy to see why Muhammad Ali and Michael Jordan were idolized. What seems even harder to acknowledge is the continued contribution of Black people to the sciences, the economy, our collective good and our gene pool.

And contributions of BIPOC folk to social justice are revered and acknowledged without fail every February for Black History Month. The black-and-white pictures of Martin Luther King Jr. linking arms with fellow protestors and John Lewis with a bleeding skull are forever etched in our memory.

But what is not so widely known is the fact that the sciences of gynecology and cancer-cell research would not be as advanced as they are today without the bodies and cells of Black women.

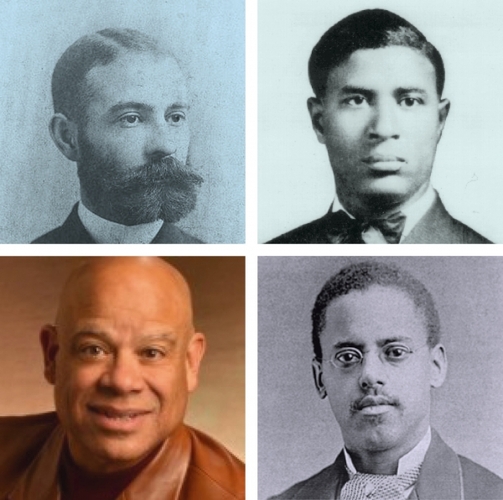

Inventors such as Lewis Latimer (inventor who advanced the light bulb), Garrett Morgan (inventor of the traffic light), Mark Dean (co-inventor of the personal computer), and Daniel Hale Williams (a pioneering heart surgeon) are not household names - and they should be.

* * *

In contemporaneous times, the Coronavirus has exposed just how essential BIPOC people are to the modern economy.

BIPOC people continue to work at jobs in the agricultural and service industries. Many have continued to work despite becoming sick because of their severe dependence on income from low–paying jobs and, in some cases, because they lack adequate health insurance.

There is a snowball effect: Due to the fact they may have inadequate health care, many BIPOC folk have underlying conditions that make them particularly susceptible to the virus and COVID-19.

Service and health-care workers are being held as heroes during this pandemic because there is widespread recognition that a nation without such industrious workers will not be able to find food in the supermarkets to maintain life and health.

Yet there are countless jobs all throughout the economy where BIPOC people toil in sufficient numbers and without the due recognition that allows them to become members of the top levels of those organizations. The U.S. economy without a pandemic relies heavily on the contribution of these seemingly non-essential workers as well.

It is time to care for all members of our society.

Dr. Stephen Bezruchka has explained that grandmothers are major social determinants of health: Your maternal grandmother is largely responsible for your health because your mother's eggs were created and developed to maturity while she was in your grandmother's womb. If your grandmother was not healthy while she was carrying your mother, it is very likely that you will not have optimum health in spite of your mother maintaining a healthy lifestyle, taking vitamins, and exercising.

Today, the U.S. has a crisis in maternal deaths, disproportionately in women of color, because of a variety of socio-economic factors. This crisis is a canary in the coal mine for the health of BIPOC women throughout this country.

We cannot control whom our children love and marry nor with whom they choose to procreate. We can pay attention to the health of women of this nation. Not doing so is like playing Russian roulette with the health of your grandchildren and their children.

In addition, not paying attention to the health of various segments of our population will ensure that we have potential reservoirs of any named or yet-to-be-named infectious disease that could overwhelm us at a moment's notice.

The United States of America is only as strong as the weakest segment of her population. If we marginalize and refuse to care for all our population, we may not be able to stand against microscopic and macroscopic threats in the near or distant future.

* * *

Black lives matter because America matters. It is time to remove the many threats from Black lives.

This nation has progressed because of, and in spite of, many fits and starts and many errors. However, in this social media/cell phone age, this country cannot continue to make large-scale errors and pretend they are not happening. The world is watching.

Your life matters as much as mine - no less and no more.

But without continued contributions from all of the major segments of our population - BIPOC, Semitic, Asian, and so on - our society will become less recognizable or less desirable.

That includes Black folk, who are carrying the kernels of innovative soul and hope that were born of our oppression and passed on from generation to generation - the soul and hope that give heart to this nation.

We will never know the full measure of the contribution of BIPOC folk to our society in the same way we will never fully know the contribution of any other group of Americans - unless those contributions were suddenly missing.

And there is the answer: We are all interwoven into the fabric of this society. Black lives matter because we all matter.

E pluribus unum.