BRATTLEBORO — For too many people, holidays are already fraught with complexity and difficulties. A global health catastrophe is the last thing they need to add to the mix.

For so many of us, the recent words of urgency from Gov. Phil Scott have created a gargantuan conflict.

We want to see family for the holidays. We need to see them. Our hearts ache for grandkids we haven't hugged. We sense the time passing for older relatives who aren't well.

Many of us desperately want - crave - connection from our families of origin and our families of choice.

Who wouldn't?

And as tough as it is, we have to be strong, the governor said.

“In the environment we're in, we've got to prioritize 'need' over 'want,'” he noted in a press conference Nov. 17, when he announced tightening of the emergency measures that had been loosening gradually.

Vermont and adjoining regions of New Hampshire and Massachusetts have been spared from the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic so far, but one look at the recent surge in coronavirus infections gives cause for concern. Take a virus that's more prevalent than ever, cram big families indoors for extended periods of time, and add holiday travel.

With so many asymptomatic people unwittingly spreading the virus, public health officials are predicting a perfect storm of grave illness and, yes, death blithely spread by the simple human contact we are craving.

“And I understand how hard it is to be asked to keep making sacrifices,” said the governor. “As I said last week, I haven't seen my mom or my daughter in nearly a year.”

Scott attributed what he described as “record growth” to “adults continu[ing] to get together with other adults - multiple households, inside and outside - in situations, usually involving alcohol, where they stop taking precautions. And then they're going to work, sending their kids to school, visiting another neighbor who works in a nursing home and spreading the virus at each stop.”

“I don't believe anyone is doing this on purpose,” he said. “But it is what's happening.”

* * *

Public health scholars have pointed out a paradox: if we're handling this emergency correctly and these precautions are effective, they will actually feel like an overreaction when they suppress spread of the virus. Unsurprisingly, reaction to the Scott administration's new travel restrictions has ranged from disappointed to grudgingly understanding to outright defiance.

“This shit is ridiculous! I'll take my chances with a 99.8% survival rate,” one Facebook friend posted. “Pass the goddamned cranberry sauce.”

I really hope he and his family and friends will be OK. Even though I couldn't disagree with my friend more strongly, I really do understand the frustration and why people are resolute in wanting to flout the new rules.

As we go through the changes that life brings us, we hold to our holidays and the traditions we create for them and from them. For many of us, these holidays become our beacons in the dark, something to look forward to, something to anchor us to the rhythms of our lives, even when those lives are changing.

If this year were normal, my own family would right now be gearing up to gather for the big feast. And we would be bracing ourselves to miss my uncle, who died in February.

At the same time, everything else about the holiday would still be there, providing continuity and comfort on an elemental human level, even with empty seats at the table.

It's why we need holidays and human connection, tradition and ritual, on a deep cellular level.

More than ever, we crave the very activities that can kill or sicken us or the people we love.

* * *

Reading the governor's words last week, I got curious, wondering about a similar time in our country's history when holidays collided with geopolitical turmoil and when the people in our area needed strength and resolve in the midst of a public health emergency.

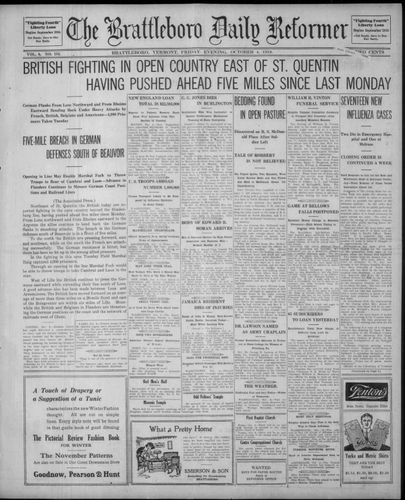

The Brattleboro Reformer in the fall of 1918 was largely consumed with two major themes: the waning days of what we now know as World War I, and the growing scourge of the “Spanish influenza.”

As the saying goes, history doesn't repeat itself, but is it ever rhyming here.

Readers first saw mention of the virus in the Reformer on April 25, 1918, with a wire story about an epidemic sweeping the military. Small news items dotted the pages of the newspaper throughout the spring, summer, and early fall.

“Spanish influenza has not yet appeared in Vermont, but there is every probability that it will,” cautioned the Reformer's editor on Sept. 20. The newspaper's town news columns - which read like an early 20th century version of a Facebook news feed - began taking note of people who were ill. And appearing on the front page of Sept. 30, 1918: the headline “BOARD OF HEALTH STOPS MEETINGS: Closes Schools, Theaters and Churches-No Public Gatherings.”

The newspaper reported “50 or more cases” of the flu in town. It editorialized that the decision to ban public events was “based on the absolutely sound principle that it is better to be safe than sorry. A serious epidemic would find Brattleboro in the same plight that hundreds of other towns and cities are in; namely, without trained nurses or doctors enough to cope with the situation.”

By Oct. 12, Brattleboro reported seven deaths out of 212 cases in a story that also included instructions for making face masks of fine gauze.

“The more one learns about the way the influenza situation has been handled in other places, the more evident it becomes that Brattleboro's comparatively light visitation thus far is due less to chance than to prompt and efficient organization,” the paper editorialized.

“With the situation so well in hand, it would be the height of folly to think of opening up until this town and surrounding towns show positive evidence that the disease has been stamped out.”

* * *

Against this backdrop of a virulent and terrifying pandemic, the “Great War” was raging and finally ended with the Nov. 11 armistice signed with Germany. Each day brought banner headlines of a lurch toward peace.

But as fall turned to winter and the holidays approached, a number of the 188 soldiers and 16 sailors from town were still in the trenches, with a weeks-long lag in delivery of letters confirming if they would ever come home. Parents, siblings, friends, and relatives - some undoubtedly ill or dying themselves and all living with the looming threat of the flu - still had no idea whether their loved ones overseas were alive or dead.

The Reformer's daily feature, “From the Boys in Service,” published haunting letters from enlisted men to their families.

“Mrs. G. C. Messer received two letters and a postcard from her son, Private George L. Messer of Company D, 102d machine gun battalion,” read the introduction to the column in the Dec. 21 issue. “She had not heard from him since before the armistice was signed, so the receipt of these letters, written Nov. 26 and Nov. 27, lifted a great deal of anxiety, as numerous casualties had been noted in the 102d machine gun battalion.”

Messer reassured his mother that he was OK. “I have not been able to write you for a long time and I suppose you must be worried, but everything is over now, and I am all right,” he wrote.

And in another letter published in that same column, Private Clarence E. Shaw wrote to his parents from France.

“Today is Thanksgiving, and we are having chicken and believe me, I woud [sic] rather be sitting at the table at home, but we are lucky to have it, so why should we kick?” Shaw wrote.

Also from France, Sergeant Carl Voetsch celebrated Thanksgiving with “a little better than the usual feed for dinner.”

“We managed to get filled up anyway, and, as one fellow said, what difference does it make what you eat if you get filled up?” Voetsch wrote to his father, local baker Charles Voetsch. “Next year at this time, we'll make up for it.”

Capt. Hugh J. Betterley looked forward to Christmas in his note from Nov. 27.

“I shall think of you all Christmas and wish I might have gotten back in time for it,” he wrote in a letter from Luxembourg to his parents, Mr. and Mrs. James M. Betterley.

* * *

I find those old newspapers haunting.

For one thing, the tone is so stoic and matter-of-fact about the sheer terror and uncertainty that a community must have been feeling about the fate of hundreds of young men from a small county in rural southern Vermont were in the trenches in “the war to end all wars.” The wait for postcards and letters must have been agonizing.

And all the while, Vermonters were ill and dying - in many cases, young people - in a world that was already no stranger to death.

I'm not going to sit here and tell anyone not to be frustrated and burned out about our present-day need for social distancing, or not to be sad or conflicted by the prospect of a lonely Thanksgiving - and maybe even other disrupted holidays this season.

I will say that these snapshots from 1918 paint a picture of similarly wrenching uncertainty, difficulty, and danger, complete with an invisible contagion turning day-to-day life upside down. And these stories offer some perspective that we are not alone. Our ancestors went through similar ordeals, similar sadness.

They were strong. They had to be - they had no choice.

Eventually, their holiday traditions returned. Empty seats at the table were saved, mourned, filled. Life moved on. Our lives will move on, too.

These gloomy, short days will mark the end of an extraordinarily difficult year. Better days are ahead. We can be strong, too. Please be safe this holiday season.