BRATTLEBORO — (1)Many school systems in the United States begin their instruction of what is called the modern civil rights movement with the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision in 1954. A few will go back as far as the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson case in order to establish an identity and setting for the modern civil rights movement.

Plessy v. Ferguson was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision that upheld the constitutionality of racial segregation under the “separate but equal” doctrine. The case stemmed from an 1892 incident in which African American train passenger Homer Plessy refused to sit in a car for Blacks.

The first event of the movement that would attract countrywide attention after the Brown decision was the decision from Rosa Parks of Montgomery, Ala., to refuse to give up her seat on a city bus and get arrested.

But is that the way it really happened?

A deeper look into the Montgomery situation will yield the fact that a young high school student, 15-year-old Claudette Colvin, was arrested for the same offense at an earlier date than Rosa Parks.

Parks' arrest, of course, sparked the Montgomery Bus Boycott, one of the pivotal events of the civil rights movement. But Colvin's arrest ultimately led to the litigation that resulted in the de facto overturning of the Supreme Court decision that had made segregation legal.

Somehow, this escaped the history books.

* * *

In Claudette Colvin's juvenile court trial, she was convicted on three charges: disturbing the peace, violating the segregation laws, and battering and assaulting a police officer. She was given a suspended sentence for a third. She was represented by civil rights attorney Fred Gray.

During the court case, Colvin described her arrest: “I kept saying, 'He has no civil right... this is my constitutional right... you have no right to do this.' And I just kept blabbing things out, and I never stopped. That was worse than stealing, you know, talking back to a white person.”

The NAACP initially stepped in to appeal her conviction, but civil rights leaders' initial momentum stopped after finding out that Colvin had been prone to outbursts and cursing. Many accounts say that the civil rights leadership distanced themselves after learning that she was several months pregnant.

On appeal, two of the charges were dropped, including the segregation charge. Colvin was sentenced to probation for assault of a police officer.

* * *

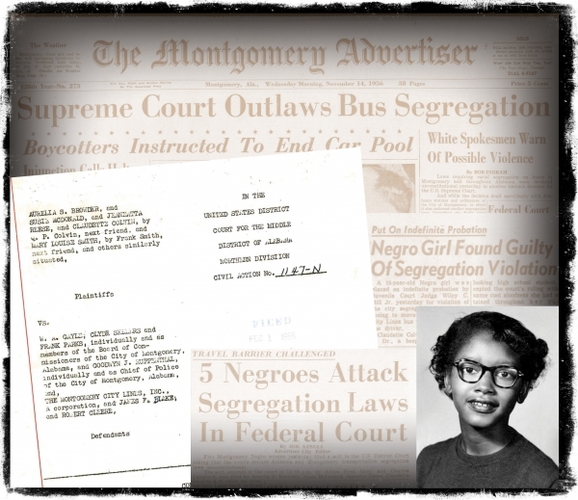

But the incident got new life in 1956 in a civil action - one that ultimately challenged city bus segregation in Montgomery, Ala. as unconstitutional.

Together with Aurelia S. Browder, Susie McDonald, Mary Louise Smith, and Jeanetta Reese (who later resigned from the case), Colvin was one of the original five plaintiffs in the court case of Browder v. Gayle.

On June 5, 1956, the United States District Court for the Middle District of Alabama issued a ruling declaring the state of Alabama and Montgomery's laws mandating public bus segregation as unconstitutional.

State and local officials appealed the case to the United States Supreme Court. The Supreme Court summarily affirmed the District Court decision on Nov. 13, 1956.

One month later, the Supreme Court declined to reconsider, and on Dec. 20, 1956, the court ordered Montgomery and the state of Alabama to end bus segregation permanently - with that quiet nod in agreement of the lower court's ruling, essentially overturning Plessy v. Ferguson and the legality of “separate but equal.”

* * *

I was able to track down Claudette Colvin several years ago while she was living in the Bronx in New York City. She was amenable to talking with me and my high school history students about her situation and involvement in the Montgomery bus boycott.

Colvin moved from Montgomery, Ala., to the Bronx, but recently returned to Montgomery. She's currently 81 years old.

This is her story, largely in her own words, from interviews my classes did with her from 2009 to 2012. She started by taking us back to the events of that day in 1955.

“I was arrested for three counts of assault and battery and disorderly conduct. I was coming from school and when I boarded the bus, I sat in a regular space where I usually sit.

“And as others boarded the bus, Black and white, they wanted to give my seat to a white lady. The bus was segregated.”

Furthermore, she said, if you were Black “you could not sit in the same row with a white person,” so by law, four seats would need to be made available for the one passenger.

“Three of us got up, but I didn't,” she continued. “I was seated by the window right by the emergency door.

“A policeman came on the bus and my three friends moved, but I became even more defiant. I refused to walk off the bus voluntarily.”

There were now three empty seats by Claudette, who was sitting alone in the row next to the window.

My students and I pondered. Claudette Colvin must have been a feisty bugger to stand up to the police that way, we thought. She was just a 15 year old - the same age as most of my students.

“You know, I was growing up in the South,” she said. “Everything was segregated. The attitudes of the white people, they still treated you like I was inferior, like second class citizens. There was a definite dividing line. When it was separated physically it was meant to be separated mentally. Growing up from early childhood, you couldn't communicate with white folks. White people could stare at you. But you couldn't look at them. You could not try on clothes; you had to know your exact size.”

“And so in February or March while I was at Booker T. Washington High School, a segregated school, we talked about Negro history and heroes that had been left out of the the system. You hear 'African American' today, but we were called 'colored' or 'Negroes.'

“So we had discussed all the injustices. And so I was really charged up because we had already discussed it in class for a month. The teacher had said we should have the whole month to talk about our history.”

You'd hear the Black community upset about school inequities, she said: mothers would complain about the unfairness, and even at school, teachers could be overheard talking about their compensation.

“The teachers, with my parents and the people in the community, were always complaining about the segregated system,” she recalled.

“There was no Black on the board of education to help control our curriculum,” she said. “So that's what it was like.”

Colvin's teachers would take advantage of the system's neglect of Black schools and use February as “Legal History Month” to explore their own heritage and the conditions under segregation.

“Students knew only two negroes from the encyclopedia. We didn't have access to books about African Americans. They were godlike to colored people. So, the teacher [would] discuss the topic, whatever topic it is and ask us to write an essay about the system.

“None of the other students were considering doing what I did - [they were] not giving up their seats on the bus.

“No one had discussed giving up a seat. It was an impulsive act. As long as you did not sit in the front of the bus, and did not sit opposite or in the same row as a white person, you hadn't broken the law. We knew the rules.

“I didn't get arrested for sitting in the white section. I was arrested for violating the Jim Crow laws. You couldn't sit beside a white person. You had to sit behind. That was the system throughout the south. That made the white people feel superior and the Negroes inferior.”

* * *

I asked: “Did E.D. Nixon [the president of the NAACP], anyone else in the NAACP, or any of the African American authorities in the city come to you, or did you go to them and say, 'I'd like to go to court and try to break down this segregation'?”

Colvin: “My mother's sister's husband told us to call E.D. Nixon because this looked like a good case,” she said. “People down there always went to E.D. Nixon, and he was kind of like Al Sharpton today. But we [Black people] always contacted E.D. Nixon about unfair employment and for unfair wages.”

“When we contacted E.D. Nixon, I found out about Rosa Parks and that she had a youth group in Montgomery. My biological mother knew [Rosa] Parks. Mrs. Parks got in touch with Attorney Fred Gray, and he took my case.”

I also asked: “Were you disappointed that you weren't used for the case and that Mrs. Parks was used instead?”

Colvin: “I wasn't disappointed. I knew they would have to have an adult because of all the litigation. There was a lot of litigation. The legal matters and the lawyers that got together and strategized to bring this to the courts. So, no, I wasn't disappointed.

“But what I was disappointed in is that people didn't know it wasn't that easy, how hard it was. Mrs. Parks' case didn't go to the Supreme Court. Attorney Fred Gray had to come and try to get Mrs. Parks' case to attack the bus system, but she was only charged with a misdemeanor. Attorney Gray went to New York to get advice from the NAACP.”

* * *

A student, Zion, asked: “I was wondering why you think Rosa Parks was more famous than you were, especially since you did it before her and you were so young when you did it.”

Colvin answered by introducing us to JoAnne Robinson, who had been the valedictorian of her high school class and fulfilled her dream of becoming a teacher.

“She came to teach at Alabama State College in Montgomery. She became active in the Women's Political Council (WPC), a local civic organization for African American professional women that was dedicated to fostering women's involvement in civic affairs, increasing voter registration in the city's Black community, and aiding women who were victims of rape or assault. She and others at the college printed boycott notices to advise the Negro community to stay off the city buses.

“The group did not feel that I was the right person. They wanted Mrs. Parks to be the person to be used because she was an adult and I was a minor. They could deal with Mrs. Parks and they were not sure if my parents would go along with our decision. Mrs. Parks was the secretary of Youth Council of the NAACP. The NAACP had prepped Mrs. Parks to be the test case.”

“In the South, they pick a person who fits a profile that will impress the white people. I am dark-skinned, and Mrs. Parks is light-skinned. That is always an issue in the South.

“The other part was because I was a teenage mother. I wasn't pregnant. They thought I was a rebellious teenager. They couldn't control me. They thought I would be more militant. [But] they always described me as kind and with good manners.”

* * *

Another student, Benson, asked: “I'm wondering what was going through your mind when you refused to give up your seat? What was the biggest reason for your actions?”

Colvin: “Well, since we were talking about slavery in school I felt like two women, Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman, were pushing me down on one shoulder and pulling me ahead of the other. S(2)o with these two strong women who had been defiant and who satisfy the [urge for](3) freedom, we had to fight for representative and first-class citizenship - and we still do, you know. That's what was going through my mind.”(4)

Another student, Maive, asked: “I was curious as to how other people on the bus reacted when you refused to move.”

Colvin: “You could hear the white people mumbling amongst themselves. And a white girl said, 'Oh, you will have to get up. It's the law.' And one of my friends was sitting in the back and she said, 'She don't have to do nothing except stay Black and die.' And then it was quiet.

“We used to have chapel programs every Friday, and we all discussed in some kind of way these things like not [being allowed to try on] clothes in the department stores, not to being able to sit at the fountains in the department stores, having to go in the back door. And you know, all of these are all these injustices that we had to go through in the South.

“So it was mostly quiet. They didn't try to get off the bus. They remained seated.”

* * *

Colvin offered us some more words about her legacy.

“Well, I appreciate talking to you, because I want people to know the real, the true story that arose upon me just sitting down on the bus. It was a lot of litigation that went down in [Rosa Parks'] case, and it did not go to the Supreme Court.

“Attorney Fred Gray looked for a woman's case that he could take to the Supreme Court that would make him successful. But the media doesn't say that. Very few people know this.

“And then a lot of people didn't know that Rosa Parks was not the first to refuse to give up her seat,” she said.

An official paper trail documents from the Browder lawsuit documents those firsts: There was Colvin, age 15. There was Susie McDonald, in her 70s. There was Aurelia Browder, a widow and mother in her 30s. And there was Mary Louise Smith, age 18.

None of them moved to the back of the bus.

Speaking of Smith, Colvin recalled that “they didn't have to drag her off the bus. But they dragged me.”

* * *

At the time of these interviews, Barack Obama was the president of the United States - the first African American to hold that office.

“Hasn't Obama done a good job?” Colvin said. “We, as Black people and African Americans, we just wanted someone to see someone in power [...](5) the very first African American couple being in the White House with two children.

“I'm so proud that God let you see that, and I wish Martin Luther King and all those other people were here to see this. They struggled to be represented and to get equal treatment.

“Well, you know, economically, everybody's suffering, but you know, Black people are suffering more - you know, five times or 10 times what other people suffer. The work is there that could be going on.”

“I just hope people teach their young children that the world is not made only for people that look like them. Please. You got to be kind to people who do not look like you because we are all part of the human race.”

Over the years, Colvin and her family have been frustrated at her omission from the official record and from our understanding of the civil rights movement.

“All we want is the truth - why does history fail to get it right?” Colvin's sister, Gloria Laster, has said. “Had it not been for Claudette Colvin, Aurelia Browder, Susie McDonald, and Mary Louise Smith there may not have been a Thurgood Marshall, a Martin Luther King or a Rosa Parks.”

But that recognition has been coming.

In 2019, a statue of Rosa Parks was unveiled in Montgomery, Ala., and four granite markers were also unveiled near the statue on the same day to honor four plaintiffs in Browder v. Gayle, including Colvin.

And on May 20, 2018, U.S. Rep. Joe Crowley honored Colvin for her lifetime commitment to public service with a Congressional Certificate and a United States flag.

“At the age of 15, she jumped headfirst into the civil rights movement by leading the first protest against racial segregation on public buses in the deep South,” Crowley said at the time. “Her leadership did not receive the recognition it deserved at the time, which is why I'm so honored to commend her courageous achievements today.”

* * *

Over the years, Claudette Colvin came to know me as “The Syrup Guy.” I had made a habit of sending her a container of Vermont Maple syrup after each of our conversations as a thank you.

At the end of one session, she reminded me, “I enjoy my maple syrup!”

More importantly, she had a question for us.

When we had finished, Claudette asked the students and me, “Am I going to be in the history book now?”