BRATTLEBORO — The town's new police chief, Norma Hardy, got her degree at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice and worked for more than 20 years in high-stakes urban environments as a public safety official with management responsibilities.

She takes over a depleted department in Brattleboro, where only 16 of 27 positions are filled(1) and the police force has had to change the structure of its shifts to manage the shortfall.

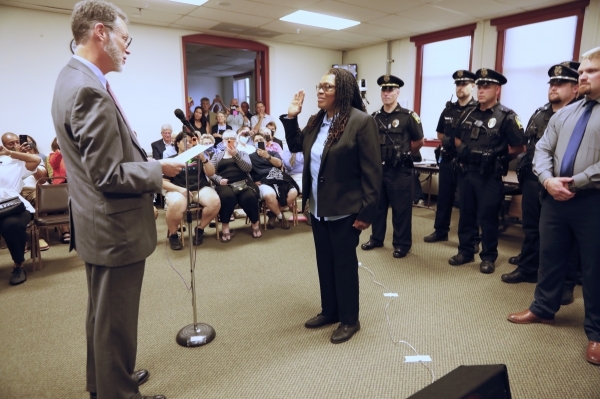

The first Black woman to run a police department in Vermont, Hardy assumes her office at a time when many pressures are placed on the BPD, from assuring equity in policing to dealing with increasing incidents of larceny and petty crime.

Chief Hardy met on Zoom with MacLean Gander of The Commons after just 15 days in her new position to talk about the challenges that the town faces with the opioid crisis and crime. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

* * *

Gander: Substance abuse disorder and the opioid epidemic are a public health crisis, and at the same time, they are a significant public safety and criminal justice problem in Brattleboro. What is your perspective on how to balance a harm-reduction approach with the need to make sure that citizens feel safe?

Hardy: That's a good question. Honestly, it is not just a Brattleboro issue. It's everywhere.

How to battle it in Brattleboro is very hard. We need to keep the people that want to make sure we do no further harm and have them understand and believe that we are doing what we should be doing in that aspect, but to also combat the dealers and the traffickers.

Those are the things that are really what I would like to focus on. It's going to be quite the battle.

With addiction, as you stated, addicts, if they're addicts, and they have money supply, they will continue to feed their habits. So if you have addicts who do not have a money supply, then they may resort to petty crimes, and then it affects and infects the entire community, because now what you have is that people can't leave the car open.

I had this conversation where I said I wanted to put out a “lock your car in Brattleboro” notice, and someone told me that when people have locked their car, then the windows get broken. So here we go - it's not even a simple thing like locking your car and being able to protect your own personal property.

It's hard to figure out how you battle these quote-unquote “petty crimes,” because “petty crimes” in a community such as Brattleboro affect the entire community. And if you have them continue, people move out of town.

Recently, we had an instance where someone painted graffiti on a stop sign. And so speaking to people in the neighborhood, to individuals that came up to speak to me, certain things were stated. And I felt kind of sad that someone who was a long-term resident said that they were leaving Brattleboro, that they did not feel safe here, and that they did not feel that it was worth it for them to stay here.

And if these small-time crimes - people also refer to them as “misdemeanor crimes” or “minor offenses” - start to grow, and you have a multitude of them and they just continue to grow, then it doesn't become small things anymore, it affects the entire area, it affects people, it affects your daily life in the town itself.

Those are things that I have to be able to sit down with my people and work with the community boards, work with the town manager's office, and to try to combat - and at the same time stand by those who are trying to give the kind of services as Groundworks and other organizations.

The problem is that it's hard to keep someone from allowing themselves to be victimized.(2) I spoke to a gentleman in my first week here, and apparently, he had allowed himself to be victimized and now he's homeless. It's hard to convince someone that you are trying to have their best interests at heart. I am a stranger to the area, and people don't know who I am. So there's a trust factor there.

I tell people that I want to help them, but if others have said that in the past and then have used it as a way to put them into the criminal justice system, then there's not a lot of trust in anything I could say.

So those are all the issues I'm facing right now as the new police chief. I do still have a hope that we can at least get a grasp on it here in Brattleboro and just make sure that people feel like their voices are being heard.

Look at the snowball effect of what is happening with the opioid addiction: We have this crisis, and now you have someone who may also lose their place to live. Now this is a person that's also homeless now, with an addiction, right? With no way to get money, with no way to support their habit or themselves, they may turn to petty crimes.

What is the biggest crime I keep hearing every day about in Brattleboro? Catalytic converters, right? I get a report quite often on catalytic converters, and someone wrote, “Maybe she can stop the theft of catalytic converters.”

Well, we are doing our best, but with the way things are structured, there really is no deterrent.

I believe wholeheartedly in the restorative justice that they're trying to put forth in Brattleboro - I think it's a good concept. I don't believe that it will work for everything that we have going on.

That's because with restorative justice, you have to have someone willing to do the process. And before you have someone willing to do the process, you have to address the fact that if this person is addicted, they need to do the process of getting clean. If that doesn't happen, there's no way it stops.

Before you are able to move forward with anything else, I'm not going to listen to you tell me that you can go apologize or you can go to community service if you are still trying to feed your addiction.

Gander: I know you are familiar with the(3) “broken window” theory - the idea that crime rates escalate when small crimes are not addressed right away. Malcolm Gladwell gave a lot of credit to how that approach stemmed crime in New York City in the 1990s. Do you think that applies here? Should we be more aggressive? And I know the department is stretched thin right now, so do you have the capacity?

Hardy: During those times, the broken window theory was abused by law enforcement people. In the poor neighborhoods, it was an easy way to basically profile to stop people. Just going by the actual structure and basis of it, that's what you would get.

And then we go back full circle of what's going on in the world today and the relationship between the community and police. I think that there are some points of it that are useful, especially when you're trying to combat this type of situation.

We know that people that are addicts. That does not mean they are criminals. But we also know that being an addict and having to have cash to feed that can turn you to do criminal acts. With minimal resources, it's hard to combat that, because most of the real people who have committed these acts are causing harm to the people who they victimize.

And if our philosophy is that we would basically police the ones that are causing the harm to others, then we need to know the difference between them and the ones that have been harmed.

If we are to do that, then we first have to have the resources to be able to stop these individuals from causing harm. We have to be gaining the trust of the individuals who are being harmed. That requires being out in the community and also making it uncomfortable for the people that are causing the harm - the ones that set up shop, so to speak.

That's what has been going on. And that's not just in Brattleboro, that's in a lot of parts of Vermont and across the country.

When you're talking about law enforcement, you can't just talk about policing. You have to talk about what happens after the police arrest someone and what's being processed through the court. What kinds of sentences are being handed out. And everyone's strained, and everyone has no resources basically now, especially these days because of COVID-19.

So I think that has created an opportune time for anyone who does want to sell drugs or move drugs or supply drugs or whatever - all the words that we use to describe the same thing: causing harm to those that can't fend for themselves.

And here's another thing, too, that I have always talked about and I want people to really think about: drugs and addiction are very, very entwined with human trafficking. Because someone may find themselves in the position that they can't pay, you know, and if you can't pay, what do you have to pay with?

You have a lot of things just stemming from these addictions. People are not just being victimized in the fact that they have to continuously feed this addiction, they've been victimized and a lot of them have not learned to say no, or are not in a position to say no, when it comes to being trafficked.

Gander: The element of human trafficking in the drug trade is something we have tried to cover, and it is difficult to uncover it because there is so much secrecy and fear. Could you talk about that some more?

Hardy: I wouldn't be standing and say I can prove anything. I just know from my experience, and some things that I am starting to notice. I was also trained as a youth services officer, and I will tell you that that's how I've seen that snowball.

We called it different things back then in the day, but it all comes down to human trafficking: utilizing someone, making them commit sexual acts, or having them go out and do other crimes, so that the main dealer would not be charged with finding places to set up shop. The pay is that the dealer continues to supply them with what they need to feed their habit.

I can't say this is definitely happening, and, of course, I would never do that, because I won't state when I can't prove. But I can speak on observations.

And the other thing too, with this opioid crisis, and with people feeling despair, and alone, and with Covid coming in, I think that the end result is even worse now than it would have been in regular circumstances.

That's because now you have more back-door, closed-door kind of activities going on. So you have people that are victimized who have no way out. And this is a very, very, very hard time - not just in Brattleboro, but everywhere in the world, of course.

In Brattleboro, I think that we're fortunate. And the reason that I came here is because I think there's hope for Brattleboro to at least be able to combat a lot of these issues.

But it will take time, and it will take cooperation - not policing, but more community outreach. I've said numerous times before that I applaud Brattleboro for the programs they've already started - some of the most unique programs I've seen - but I also believe that people have to understand that it's better to work with me and work with my department, and therefore maybe we can help some of the victims.

Gander: This is an unfair question for someone who has been here only 15 days, but what is your vision? How do you see things unfolding if you get the resources you need and community support?

Hardy: I think what I see is different. I see the police moving back from a lot of things. First of all, I'd say I see us not having to be social workers. And I see us not having to respond to every job, because right now if it's a mental health crisis, the police are always needed. But I see us being able to not only just be the police but also be public servants. So when someone wants our help, they'll feel confident in asking for our help, that we're going to come and do our best to make them feel safe.

There's still a lot of apprehension in discussing police matters, and I do that quite often, with the community, with the town manager's office. To gain support is going to take a lot of work, especially from people who just don't believe that there can be that kind of working relationship with the police.

And I would like to change a couple of minds. I know, I won't change everyone's mind. That's not realistic. But maybe I can change a couple of minds, even if I can just get some people to just move to the middle instead of all the way to the extreme of abolishing or disbanding the police, if I can get some people to just see that there are instances where the police are needed. And get them to see that I am not here to say “police, police, police.” There are certainly areas where police are not needed.

I think that's why everyone needs to have these open conversations, even if we disagree. I would like to be able to have conversations with people that don't agree with me and that I don't agree with, but still in a respectful manner. I don't ever attack anyone's ideas, even if I don't agree with them. And I like that same kind of mutual respect.

I do want people to understand there are people within your own community that are telling me we need the police, that they're afraid to walk the streets of Brattleboro. I'm sure that some longtime residents would have never thought they would be saying that in Brattleboro now.

But at the same time, these people love Brattleboro. They love their town, but they fear that town right now. And my hope is that there will come a time when that's not true anymore.