Censorship. It's a word, an idea that ignites the ire of people who care about the arts. We all know censorship is bad - it's the stuff of fascists, or worse: of prudes and numbskulls.

Rejecting censorship is righteous. It reveals a person's high-mindedness and sophistication.

Defending artistic freedom is easy, but defending your right to work with an alleged “child molester” (as former Brattleboro Union High School teacher Zeke Hecker described himself in a letter to a survivor)?

Not so much.

Recently, in coverage of my story [“No more secrets,” Viewpoint, Aug. 11] about the multiple investigations into Hecker's conduct with students over the years, Kevin O'Connor wrote in VTDigger that I distanced myself from Hecker because of discomfort with “his affinity for literature with sexual themes.”

I want to clarify: The literature and its sexual themes did not cause my discomfort; Hecker's use of it to groom and harass his teenage students did.

This is an important distinction.

I did not object to John Donne's poem “Elegy XVIII: Love's Progress.” But I objected to Hecker asking a girl to stand in the middle of the classroom while he read it, and then gesturing at her body as he did.

He began with her hair, “a forest of ambushes,” and proceeded downward, past brow, eyes, cheeks, and her “swelling lips,” all described in artful detail; past the “Sestos and Abydos of her breasts,” and her navel; until finally he reached another “forest” and the girl was allowed to sit again, but not before we were asked to “consider what this chase/Misspent by thy beginning at the face.”

I remember only the girl's face.

Neither do I object to a video of Debussy's ballet based on the poem by Stéphane Mallarmé, “Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune,” choreographed by Nijinsky and danced by Rudolf Nureyev.

Nureyev beautifully portrays the faun chasing and flirting with a group of nymphs, until they dance away from him, leaving only a scarf behind. In the final scene, the faun carries the scarf away and appears to masturbate with it.

But one BUHS alum told of a time Hecker brought a group of students to his house in the Guilford woods to view the 10-minute video together. She remembers being uncomfortable because they watched the film in a completely darkened room that was “pitch black,” with the door closed.

Hecker lingered over sexual passages in the literature he taught, and in doing so, he accustomed us to explicit discussions with a teacher. He repeatedly chose material that depicted sexual contact between adults and minors until that contact seemed normal.

These are grooming tactics. Some predators use pornography. Hecker made literature and art seem pornographic.

* * *

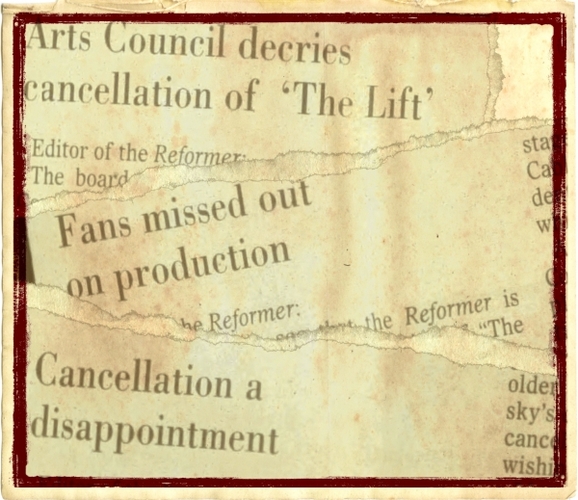

In 2008, Brattleboro's arts community cried “censorship” when Hecker's play The Lift, which he adapted from a Thomas Mann novel, was cancelled because an audience member complained about a high school student playing a sex scene with an adult.

The person - still unidentified - complained to Bob Kramsky, director of the play and a board member of the Vermont Theatre Company. Kramsky cancelled the show, supposedly under threat of a lawsuit, the grounds for which were never clear.

Kramsky never revealed the complainant's identity, nor did he speak in their defense during the ensuing months.

Members of the arts community publicly attacked the person who raised the issue. In letters to the editor, they called the person a “self-appointed censor,” and accused them of “political correctness.”

The entire board of the Arts Council of Windham County signed a letter saying “the situation reeks of censorship,” though they acknowledged that the stated reason for the complaint was that the actor was too young (he was 18, but still in high school). Hecker called the person a “coward” and a “bully.”

When Hecker, Kramsky, and the Vermont Theatre Company reprised The Lift in March 2009, their efforts were lauded as a triumph of artistic freedom.

What Kramsky did not tell the public was that in the interim, his and Hecker's former English department head, George Lewis, had told him about “possible inappropriate relationships” that Hecker had had with his minor students. Kramsky admitted this in his interview with police two months after the show closed. He said Lewis had approached him about six months earlier.

If his account is accurate, Kramsky must have known even before rehearsals began that he was producing a play about statutory rape from a script by a man who had allegedly committed the same crime.

* * *

Objections to Zeke Hecker's behavior were never about censorship - from the content of his syllabi to the content of his plays - and the suggestion they were was a straw-man argument in defense of working with a man who behaved in indefensible ways. It was a denial of the real concerns of people who tried to speak out to protect youth.

Vermont Theatre Company's apology and statement of solidarity with survivors after the publication of my piece [“Some statements in response to 'No more secrecy,' Letters, Aug. 18] was commendable, and I believed its sincerity. But I was disturbed by their suggestion that the problem was that the play had “caused mixed feelings” and was “triggering.” This continued focus on content once again missed the mark.

Personally, I am not concerned about the content of future plays the company might produce. I am just hopeful they will take better care to protect youth, and that they will not prioritize the voices of harmful men.

This is my hope for all of Brattleboro's arts community. I don't believe those letter writers intended to hurt anybody. To champion the arts and artistic freedom is a noble and necessary cause.

We just have to be mindful of the voices we may inadvertently silence in our fervor.