BRATTLEBORO — How can you begin to fathom the loss for the family of Rita Corbin and Daniel Bliss?

How do you even begin to honor, to acknowledge, to celebrate, to mourn two lives lost so suddenly? How do you move forward with your own lives in the aftermath?

“Along the way, death and tragedy can bring you closer together,” says Maggie Corbin, Daniel's aunt and one of Rita Corbin's five children. “We're all close here, and that's because of our mom.”

“One of her gifts was raising kids that care about each other,” she says.

That care has manifested itself since the accident in Bernardston, Mass., on Nov. 6, which killed 17-year-old Dan instantly and sent his grandmother, Rita, to an intensive care unit in Worcester, Mass., until she died Nov. 17.

The extended and close-knit Corbin family has become even closer.

Last week, clustered around the living room of Coretta Corbin Bliss - who lost both her son and her mom - her family shared their admiration and memories of Rita and Dan.

The first things you notice about the Corbins: a) they are brilliant and creative, and b) they talk really, really fast - the latter, perhaps, a necessary survival strategy for getting a word in edgewise in a large family.

And they unstintingly and lovingly painted a picture - as much as six people can in an hour or so - of two creative forces, one an emerging talent just on the verge of starting adult life, the other an octogenarian still in her creative prime after a formidable and distinguished career as a versatile, professional, and wonderfully subversive artist.

* * *

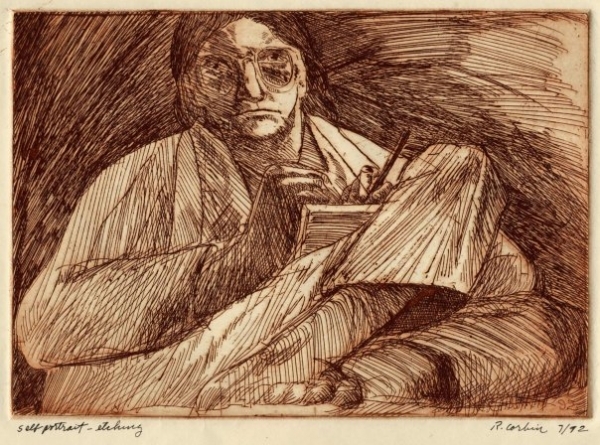

The artwork of Rita Maria Linley Ham Corbin combines an elegant simplicity with graphic impact. Her styles and media range from intricate scratchboard to bold woodcuts to colorful painting, from fully realized self portraits to abstract expressionism, from stand-alone spot illustrations to artwork that integrates Bible verses and other text.

She saw the artwork in everything, they say, and everything became a catalyst for her artwork. In the 1980s, her son Martin says, she first encountered the then-novel Macintosh computer and began drawing with it in the showroom.

“It was just another tool, another medium for her,” says Coretta's sister, Maggie, a graphic designer for the Community College of Vermont.

By her family's accounts, Rita was an artistic rebel who was far more interested in creating art than in capitalizing on it.

“Our mom was pretty amazing,” Coretta says. “I didn't fully appreciate what she did - I knew she was a great artist, and she was drawing all the time.”

Maggie describes her mother's early work as “really, really good” and “really refined.”

Though she was trained as a commercial artist, the concept of art as commerce “went against the grain,” Coretta says.

In 1950, Rita became involved in the Catholic Worker movement. The nonviolent, pacifist movement founded by Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin has no hierarchy, titled leadership, or doctrine, and is not even officially part of the Roman Catholic Church. Its basic philosophy is taken from Jesus' words in Chapter 25 of the Gospel of St. Matthew: “Whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.”

It is perhaps best known for its “houses of hospitality” in various cities and towns around the country that provide food, clothing, and shelter to those in need without requiring religious practice, or attendance at services.

Summing up what the movement is about, the Catholic Worker Journal writes that it “is grounded in a firm belief in the God-given dignity of every human person.”

Her family says that is how Rita Corbin lived her life.

The Catholic Worker movement generated a newspaper of the same name. Corbin contributed her artwork to the paper, starting in 1950. There, she met her husband, editor and literary critic Martin Joseph Corbin, who eventually served as the newspaper's editor.

She contributed artwork to the newspaper for the next 60 or so years, until the car crash. “She was in intensive care and barely hanging on,” Coretta says, noting that her mother said, with anguish and dismay, 'I'm an artist, and I can't move my arm.'”

For more than 40 years, Rita produced an annual Catholic Worker calendar. She certainly didn't do it to make money. The kids had to remind her every so often to raise the price to meet production expenses, and if someone without means wanted one, she'd send it.

It was never about the commerce.

It was all about the art, and the art - in a variety of media and of topics as diverse as the beauty of nature and the despair of inner-city squalor - provided a window to her moral and ethical compass.

“She had extreme principles,” Coretta says. “She was quietly political. She was going to tell the truth as she saw it. She was strongly anti-war, anti-death penalty.”

Sara Corbin, telling a story of the time that someone accused her mother of being a liberal, says that her mother strenuously denied the accusation.

“I'm really a radical,” Rita told him.

* * *

Rita came to the Brattleboro area in the early 1980s, and the family eventually settled around her, and around one another.

Eventually, she lived across the river in senior housing in Hinsdale, N.H. But her family says that she never fully felt part of the culture there.

“She said, 'They're all old people there,'” Coretta recalls with a smile.

As she grew older, she cherished the freedom to pursue her artwork without the constraints of as many parenting responsibilities.

But if Rita's artwork was at the center of her life, that life in turn revolved around her five children, spouses, partners, grandchildren.

It was a life lived according to what her children describe as “the Corbin Way”: impulsive, impromptu camping journeys and road trips. She would jump in her car at a moment's notice to participate in a family gathering.

“She could talk to anybody,” Maggie says.

Her family laughs as they recount an anecdote from about 10 years ago. Rita's car broke down in a strange town that was vaguely familiar. She realized that the name of the town rang a bell because she sent one of her calendars to a customer who lived there.

So without fear or reticence, she looked up the customer and sought help from him.

Her capacity for the impromptu “makes me wonder what I am doing running around in this rat race,” observes Martin's partner, Stephanie Salasin.

Her family speaks of her measured and wise counsel, that came in so many varied forms, whether as art lessons for Stephanie's daughter, Sequoia, or simply as “incisive comments, with little drops of wisdom to impart,” Stephanie says.

“She would criticize without making you feel criticized,” Sara Corbin says. “She could argue without making you feel attacked.”

The worst she would say about someone? Calling them “a difficult person.”

And the connections she made in the process: they were lasting. They were genuine. And they continue to come in and surprise Rita's family in the aftermath of her injuries and her death.

The customer she looked up when her car broke down?

He played music at Rita's bedside after the accident.

* * *

A s the Corbin family mourns their mother's life fully lived, they're also mourning the lost potential of Daniel Bliss.

“Really funny,” his mom says. “That's the first thing I remember about him. He was turning into an amazing young man.”

His family paints a picture of the Brattleboro Union High School senior as a charismatic, outgoing, affable, artistic young man who was just beginning to realize his dreams.

The aspiring 3-D graphic designer methodically saved up his money from his job at Price Chopper, first to buy a fully-loaded gaming computer, then to buy a season's pass at Mount Snow. He was just starting to save up for the car he would need to use the snowboarding pass at the ski area.

Marty works quietly on his iPad, pulling up one of several websites that he and Stephanie have worked on to honor his mother and his nephew, and he clicks on a sample of Dan's art. It is a black-and-white wash painting of an African-American man holding a baseball, closely cropped. The painting's composition is dynamic; the subject's facial expression is nuanced, the eyes hauntingly expressive.

“It's sad for me [to think of] all the artwork that he will never do,” Coretta says.

Dan harbored an innate artistic talent, but, his family says, he resisted exploiting it. When he did his art, he did it for its own sake and because he loved doing it.

“He didn't say, 'Wow, I'm good at this,'” his mother says. “He really just wanted to get better at it. He didn't care what he could get out of it.”

Just like his grandmother.

* * *

T he realities and consequences of that horrible day in Bernardston are still unfolding. The family has split the cost of two funerals, but they still have no idea how much money they will owe for Rita's 11 days in the intensive care unit.

A second of two benefit concerts will take place in Keene, at Heberton Hall, next to the Keene Public Library, at 6 p.m. on Friday, Dec. 9.

Scheduled to perform: Dave Evans, The Cold River Ranters, Rise!, and Long Leash.

The family has also set up fundraising efforts at two websites: one for Rita and the other for Daniel. Both sites let friends and neighbors offer financial support to the family via PayPal, and Rita's calendar and cards will continue to be sold on her domain.

The family members have pooled their talents to produce this year's calendar, which Rita left partially completed. All that remains is to look through Rita's meticulously catalogued artwork to finish selecting several images.

In the meantime, they help one another process their grief. They sing together. Coretta, a well-known area musician, has posted to Facebook a video montage memoriam to Dan with Coretta's cover of Bob Dylan's “Forever Young.”

And they cherish the constant stream of stories they hear in their grief. The stories from the people who have been touched by Rita's artwork. The solace and kindnesses from friends and neighbors.

“We have deep, deep sadness, but we have deep, deep, joy - and gratitude,” Stephanie says. “One of the gifts of deep sadness and deep pain is you feel other things deeply, too.”

“One of the dangers if you shut out the sadness and anger is that it will make you numb,” Sara says.

“Our family has changed,” Coretta says. “But we're still family.”