BRATTLEBORO — As contract negotiations between the Brattleboro Retreat and United Nurses and Allied Professionals Union Local 5086 have concluded, the question of how to care for the caregivers remains unanswered.

During informational pickets by union members in front of the Retreat over the past few weeks, staff members raised concerns about an increasing rate of violent incidents for direct-care staff at the 178-year-old private, non-profit mental health facility.

Workers' Compensation numbers from the Vermont Department of Labor and incident reports from the Brattleboro Police Department, pointed toward an increase for 2012.

The Retreat accepted patients in August 2011 from Vermont State Hospital in Waterbury after Tropical Storm Irene flooded the facility.

Staff and community members have questioned whether state patients have been at the center of increased staff injuries. The data collected for this article did not absolutely dispute or confirm that theory.

According to Peter Albert, Senior Vice President for Government Relations and Managed Service Organization, patients' “acuity” has increased over recent years.

Patients once arrived at the hospital with one diagnosis, like depression. Now, patients arrive with multiple diagnoses - like depression, a substance addiction, and physical health issues - that complicate and deepen their clinical needs.

By the numbers

According to numbers from the Labor Department's Division of Workers' Compensation (DWC), 2012 showed an increase in the number of injuries to staff by patients over 2010 and 2011.

For 2010 and 2011, DWC recorded 49 reports of employee injuries at the Retreat in 2010 and 58 injuries in 2011. This is an average of about four injuries a month over 12 months.

The DWC had data for 2012 through October, which totaled 48 reports, or an average of 4.8 reported injuries a month for 10 months.

Accident descriptions from the DWC ran the gamut from “repetitive motion while using a keyboard,” to slipping on ice, to injuries obtained while restraining patients.

Other entries listed more serious encounters like employees being punched in the head or in the eye, or workers suffering injuries to arms and wrists while blocking punches or kicks from patients.

Of the accident descriptions using language that suggested a violent altercation, 2012 showed the higher number.

The incident reports from the Brattleboro Police Department (BPD) tell a similar story.

The Commons requested documentation of all incidents involving assaults at the Retreat for 2010, 2011, and 2012 to date.

BPD reviewed 282 incidents, of which 57 incidents involved “physical contact between patients or patients and staff” were reported. Of the 57 incidents, 15 dealt with violence between patients.

In 2010, the BPD, which redacted identifying patient information, recorded 22 incidents, of which six described patients acting out in a way that resulted in staff injuries.

One example occurred on Sept. 1, 2010, when Retreat employee Chris Guido told BPD that a patient “lunged across the desk and grabbed the other staff member around the neck.”

According to the incident report, Guido said he “was punched three times on the head and poked in the eye, knocking his contact (lens) out of his eye.”

In 2011, the listed incidents dropped to 15, of which six listed injuries to staff. In two of the six, officers noted patients' threatening language had visibly shaken staff and other patients.

The BPD's 2012 data covered the first 10 months of the year. Out of 22 incidents, eight listed staff injuries.

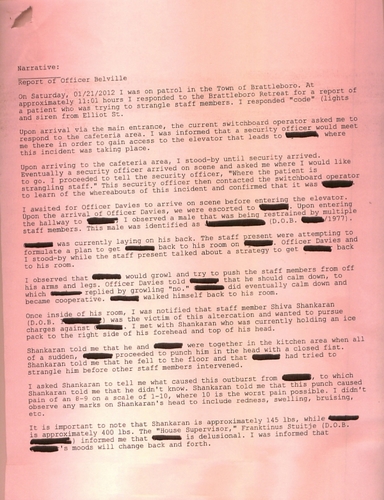

A report from Jan. 21, 2012 recounted a patient punching and grabbing staff member Shiva Shankaran by the throat. BPD noted in the incident report that the patient “has been assaultive towards the staff at the Brattleboro Retreat in the past, along with other agencies in northern Vermont.”

Of the 57 reports given to The Commons, the BPD submitted 10 incident reports related to staff injuries by patients to the Windham County state's attorney for review toward potential prosecution.

In the past three years, only one incident has led to a court appearance.

Vermont law requires that a defendant meet the legal criteria of being sane and competent. A person charged with a crime must have the capacity to differentiate between right and wrong and also participate in his or her defense.

In a previous interview, Assistant State's Attorney David Gartenstein said that meeting the legal criteria to prosecute someone undergoing treatment for mental illness is a high bar to reach.

'The aftermath of assaults'

The difficult call is highlighted in an incident report written by BPD Lt. Jeremy Evans chronicling an incident in 2010 when officers needed to disperse 15 patients refusing to comply with instructions by staff.

During the officers' response, Evans was pulled to the ground by one patient.

Verbal commands from officers and the use of knee strikes failed to disengage the struggle, Lt. Evans reported, noting that he eventually used his Taser on the patient, who then released him.

In his narrative, Evans wrote of his experience on the unit.

“We often respond to calls there [unit name redacted] for staff members being assaulted, and occasionally officers are assaulted while dealing with patients as well.”

Evans continued: “I have seen and investigated the aftermath of assaults, attempted suicides, and successful suicides at the Retreat and involving escaped, or runaway, Retreat patients. I have also witnessed and intervened with Retreat patients actively injuring themselves or attempting to commit suicide.”

“During these altercations, I have taken various weapons from patients to include razor blades, rocks, broken glass, writing implements, kitchen utensils, and other rudimentary stabbing weapons.

“I also am aware from past experience and training that most of these same patients have been physically abused in the past, and the use of force against them can be detrimental to their ongoing treatment and healing process,” wrote Evans.

Crossing a line?

But, asked some employees in conversations during November's informational pickets, where is the line between honoring a patient's mental-health issues and holding a patient accountable for his or her actions?

In some cases, staff have said that patients “know what they're doing” when acting out violently.

Two incident reports record patients saying they preferred prison to the Retreat. Officers reported that patients asked if they would be incarcerated if they hit staff members.

Retreat nurse Beth Kiendl met with Officer Maeghan Gagnon on Sept. 18, 2012 to report a female patient who asked “If I punch her [Kiendl], will I go to jail?”

According to the incident narrative, the patient “grabbed Kiendl and pushed her into a closed door and pulled her down to the ground.”

In a similar incident, a patient kicked a staff member, Seth Windsor, in the groin.

When questioned, the patient said she “was acting out in an attempt to get transported back to Woodside.”

According to the Vermont Agency of Human Services website, Woodside is a juvenile rehabilitation center for youth under the jurisdiction of the Department of Corrections.

'Jail mentality'

During a Nov. 27 interview, hospital employee and Union Unit President Tom Flood said it is hard to determine when a patient has crossed the line and needs to be held accountable.

In Flood's opinion, employees at the Retreat understand and empathize with patients' mental-health issues and occasional violent actions.

But, he added, some patients come to the units who, instead, should be incarcerated.

These patients arrive with a “jail mentality” and lash out, not because of a psychological cause, but because they don't want to take direction, said Flood. These episodes typically compel staff to file reports with authorities.

Patients acting out affect other patients in addition to the employees, said Flood. “Once they act out, it has a domino effect [on the unit].”

Other patients' violent behavior can trigger fellow patients' past traumas.

“There's never just one crisis that happens,” he said.

Flood said the community should understand two things.

First, just because a person has a mental illness does not mean he or she is violent or out of control, he advised.

Second, he said, the community needs to understand that just because he and his colleagues work at a psychiatric hospital, “they do not give up rights to use [laws] to make sure they stay safe.”

Flood expressed concern that the Retreat's decision to cut the Therapeutic Activities Services and in-patient chemical dependency counseling programs would increase agitation on the units because patients wouldn't receive enough activities with therapeutic components.

He added that when he has interacted with BPD, officers have provided assistance, but they indicated it was unlikely that filing an incident report would result in prosecution.

When asked if the Retreat overall was helping support a safe working environment, Flood responded, “at this point in time, I'd have to say no.”

Contract negotiations

At the time of the interview, Flood said that management was still discussing in contract negotiations the reduction of staff, which he felt would only contribute to more staff injuries.

In an interview on Tuesday, Albert said that the Retreat administration has been looking at similar data to that used in this news story, and its conclusion is that while incident reports are up, workers' compensation claims are down.

“We're aware of it, and we're looking into it,” said Albert of the claims of Retreat employees that their safety has been compromised since the introduction of patients from the state hospital and the corrections system.

Albert said that at issue was the number of patients involved in these incidents, and the seriousness of them.

Calls to the Department of Mental Health were not returned by press time.