January is the month when Vermonters pore over the seed catalogs and dream wistfully about how their flower and vegetable gardens will grow in the coming year.

And, for more than 60 years, one of the determining factors for which annuals and perennials will survive in Vermont is the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Plant Hardiness Zone Map.

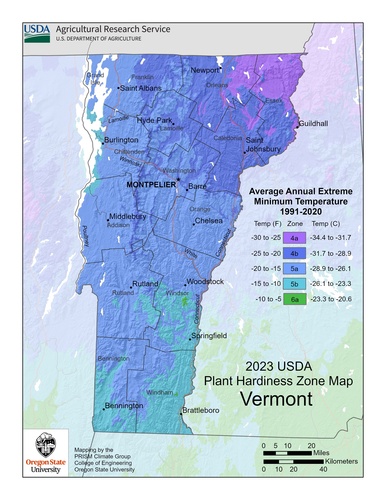

The map assigns a zone number to an area, reflecting the average annual extreme low temperature in an area over a 10-year period. Gardeners use these zones to determine what plants will thrive in a specific place and when and how they need to be handled, planted, and tended.

Last fall, the USDA updated its zone maps for the first time since 2012, and the Windham County map has seen some adjustments.

West county towns such as Londonderry, Jamaica, and Wardsboro have moved from Zone 4b (20 to 25 degrees below 0) to Zone 5a (15 to 20 degrees below zero).

The rest of the county has moved from Zone 5a to Zone 5b (10 to 15 degrees below 0).

Most of Vermont is now in Zone 5a, with the Connecticut River Valley from Windsor to Vernon, parts of the Champlain Valley, and southwest Vermont south of Bennington in Zone 5b. Isolated pockets of Putney and Brattleboro, including downtown, are in Zone 6a.

Only the Northeast Kingdom is in Zone 4, with the coldest winter temperatures in the extreme northeast corner of Vermont.

So, what does this mean for Windham County farmers and gardeners? The Commons asked Vern Grubinger, the vegetable and berry specialist with University of Vermont Extension, for some advice.

He said that while the data suggest Vermont winters are getting warmer, growers should still be cautious.

"Growers should plan for temperatures that are colder than the averages on the zone maps and select the plants that can survive colder temperatures," Grubinger said.

Extremes get more extreme

While growers in Vermont factor in the changes in the USDA maps when evaluating what to plant and where and when to plant it, Grubinger said older farmers tell him that the growing season used to be more predictable than it is now, and it's simply not that way any more - with 2023 being a prime example of the extremes of Vermont weather being more extreme.

In Windham County, we saw a brief burst of sub-Arctic air in early February wipe out the peach crop. In mid-May, an unexpected freeze wiped out the apple crop. In July, heavy rains and flooding left fields waterlogged, while long stretches of days breaking the 90-degree mark throughout the summer put further stress on plants.

As extreme as 2023 was for weather, climatologists say we can expect more years like it in the coming decade.

The Fifth National Climate Assessment, a report that evaluates the current effects and future trends related to climate change across the U.S., was released last fall. The Northeast Regional Climate Center at Cornell University took a deep dive into the report and found our region has gotten warmer and wetter over the past 60 years.

The report found that heat waves in the Northeast are happening more often, last longer, and are more intense than in past years. The Northeast has also seen warmer winters, with warmer nights and fewer cold days, a trend that will continue in the coming years.

The Northeast has also seen a 60% increase in the number of days with extreme precipitation - defined as 2 inches or more of rain in a 24-hour period.

"While the changes in the new [USDA] map won't have a big impact on growers, it's the extremes in weather, as we saw this year, that will be the problem." Grubinger said.

Timing, and risk management

Grubinger said a big reason why 2023 was so hard on growers was the timing of the weather events. The deep freeze in February came at a time when peach trees are most vulnerable. Likewise for the May freeze that happened when apple trees were budding.

But he said the freeze that destroyed the apple crop in Windham County had little effect on high-bush blueberries, because it came after that crop's most vulnerable period.

And, with the late summer months being mostly dry, Grubinger said some growers were able to salvage a decent season with their fall harvests.

Growing anything in Vermont isn't easy, he said, but one way that some growers manage risk is doing more high-tunnel growing - those long plastic-covered tunnels you see at some local farms that allow farmers to grow greens and other plants outside the usual growing season.

Other ways that Grubinger said perennial growers can move the odds in their favor include optimizing irrigation and fertilization so plants are not stressed by drought or a lack of soil nutrients during the growing season.

Mulching also helps protect tree and plant roots from freezing in the winter, while burlap and snow fences can protect foliage from cold winds.

In short, he said, planning and preparation will improve the chances your garden can make it through the extremes of a changing Vermont climate.

"Early or late frosts are not going away," Grubinger said.

This News item by Randolph T. Holhut was written for The Commons.