VERNON — Students at the elementary school welcomed a special guest during the first week of May.

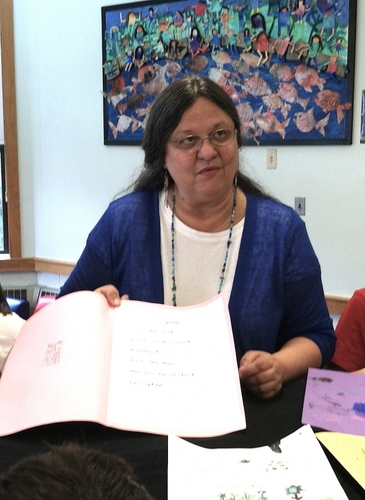

Judy Dow, an Abenaki teacher, storyteller, and basket maker, was the school's visiting artist-in-residence. She worked with all the students from Kindergarten through sixth-grade on topics teachers identified as fitting with their curriculum, said fourth-grade teacher Maresa Nielson.

Nielson serves on Vernon Elementary School's Diversity Committee and described the group's work as “about equity for all of our children and staff.”

Much of the history of non-European settlers “has been erased, and it's our job to put the puzzle back together,” she said.

“Our main [activity] is the yearly artist-in-residence,” Nielson noted.

The committee chose Dow to work with the school, and her visit was funded by a $2,250 grant from the Vermont Arts Council.

Dow, whose lineage is Abenaki and French and “nothing else,” she said, lives in Essex Center and travels across the country teaching history, science, and math through art.

“People of the past were scientists and mathematicians,” Dow said, adding, “they still are.”

“Teachers tell me I'm not like any other artist-in-residence they've had because I want to teach science and math,” she said.

Dow said she has taught in 46 states, 157 towns in Vermont, and four Canadian provinces.

She said the Abenaki tribe's original spelling was “Wabanaki,” which meant people from the white, or dawn (waban), land (aki). When the French came to this side of the Atlantic, “they had no sound for the letter 'w,'” Dow said, so the spelling changed.

The original pronunciation, which places the accent on the second and fourth syllables, was altered twice; first by the English and then by the Dutch.

At the end of Dow's week, the school library was turned into a sort of art gallery. After lunch on Friday, May 6, every 10 minutes, a teacher brought their class into the room, where students' projects were arranged on top of low bookshelves and large, round tables.

Dow played docent, leading the children through the displays while she talked about the projects, why she chose them, how they matched the curriculum, and what lessons might be learned from them.

Some of Dow's work earlier that week included taking the fourth-graders on walks near the school to study the land and see beyond “the bronze road signs” commemorating the settlers' notable events and sites.

As Dow said, this leaves out an important part of Vernon's history: namely, that of the native peoples. For their project, she had students make maps of the town to “replace the narrative,” she said.

The sixth-graders made small, colorful “landscape baskets,” woven of wood and yarn. The composition of the baskets, in the colors and textures the makers chose, “tells the story of the terrain,” Dow said.

Dow took the second-grade class on a walking tour from the school to Miller Farm, where she instructed them to “just read the land” beyond houses and buildings, she said.

During the walk, she said she told them about Lake Hitchcock, the glacial lake that formed approximately 15,000 years ago, and sat along what is now the Connecticut River Valley, running from St. Johnsbury to Rocky Hill, Conn.

Dow pointed out the terraces along both sides of the Connecticut River, and how those were the riverbed, formed when Lake Hitchcock receded, eroded into a river, and drained into the Long Island Sound.

The kindergartners made toys: furry little mice made of milkweed pods.

“This is a lesson from Judy Dow in 2016,” Dow said to a group of older students. “Put down the mouse, get out from behind the computer, and go outside where the real mice are,” she said.

“Go outside and find the other mice and run and play,” she said, adding that while computers can be useful, “you have to have balance in your lives.”